The Trial of Chicago 7 carries eerie similarities to Indian politics today. Political imprisonment without fair trials is a reality. Free thought that challenges the power structures is being muzzled. However, the critical difference is that a large section of India remains woefully ignorant, or stubbornly quiet to these highly disturbing violations of the constitution of our democratic country. So what role can cinema play?

We are not new to mainstream Hindi cinema taking political stands. In the 1950s, Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zameen brought to life the woes of a farmer struggling to save his land from the impending industrialisation – ironically an issue still faced by farmers today. Or Sujata, which held a sharp view on caste issues with an inherently human story. Raj Kapoor’s Shree 420 was a scathing critique of capitalism, and slighting of dreams in post independent India, rising from the clouds of colonialism. Guru Dutt’s Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam, and Kaagaz Ke Phool – set in crumbling realities of feudalism and studio structures respectively – contested shifting ideas of power, and the idea of identity and individual.

A still from ‘Do Beegha Zameen’.

In the 60s, we had what was considered ‘benign cinema’ comprising films by Hrishikesh Mukherjee and humane stories by Gulzar – but they were actually deeply political. Gulzar’s Aandhi, for instance, was about a lot more than the personal life of a female politician. It was about the idea of politics itself, both from a perspective of gender and the actual politics of the country. In films like Golmaal, amidst the humour, lines like ‘Emergency hatt jaane ka matlab nahin hai ki aap manmaani karein shor machaayein (Emergency doesn’t mean that you’d start doing anything you like)’, or ‘down with personality cult’, are sharp critiques of the politics of the day. Or Mukherjee’s Guddi that examined ideas of power skews basis class.

A still from ‘Golmaal’.

The 70s saw the rise of the angry young man – a representation of the angst of an India that had by then been independent for over 30 years, but still had many dreams to realise. The discontentment with power, and the ability to contest it, was shown in Kaalia, Deewar and many more such films.

As India’s dreams moved to becoming more cosmopolitan, Hindi cinema’s storytelling changed. They arguably became more individual-centric, more about people wishing for the right partners in their lives than political realities. The escapism in cinema was now complete. As India flocked to not watch films that told their stories, but told stories of what could be their potential dreams – that could well never be realised.

Also read: As a Pakistani, I Grew Up Watching a Very Different India in Bollywood

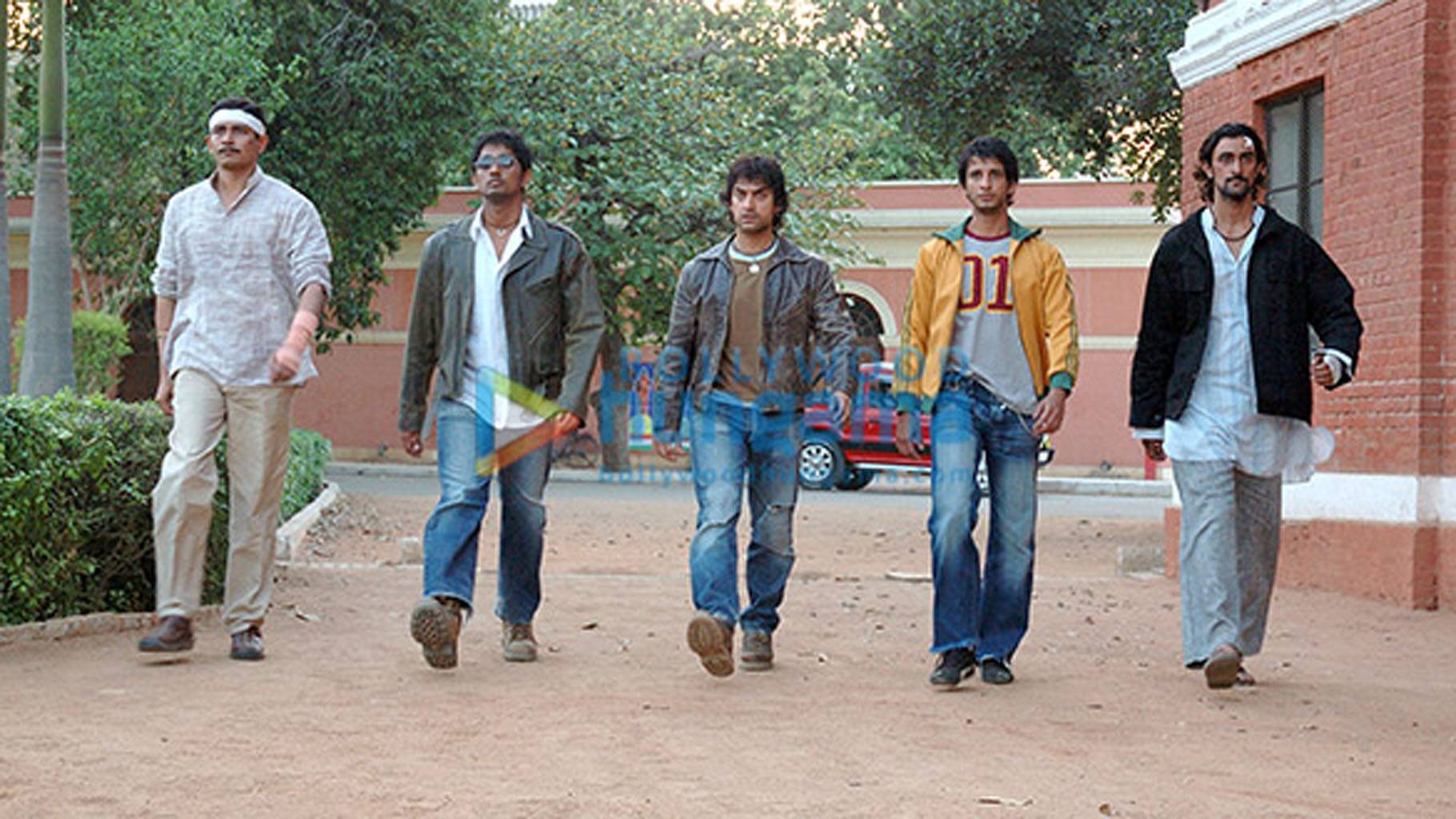

And we still live in that hangover. Rang De Basanti, Yuva, Lage Raho Munnabhai, PK, Article 15 and Mulk, are the few exceptions from an industry that churns out over 100 films a year. These films confronted politics, religion, their shortcomings and set themselves squarely in the middle of a system that is determinedly corrupt, wielding power as it sees fit. They fearlessly attacked the several banalities that we are privy to around us, with narratives that moved us to think. But where are the other political discourses?

A still from ‘Rang De Basanti’.

A handful of films examined the lives of Bhagat Singh, Rajguru, Sukhdev, Gandhi and so on. Even then, we have always focused our storytelling on who the people would’ve been and why, than their very distinct contributions to the political landscape of our country. Rarely do we find stories, narratives or discourses, examining one specific incident that made a pivotal shift to political realities. Rarely do we create films that examine the current political situation and the need to solve it, or tell its stories through one of our most pervasive mediums.

Political realities need to move beyond just backdrops for the same love stories. It needs to be an active protagonist of the narrative itself. Article 15 stands out in its bold look at caste politics and impending intersectionality, and the need to change political realities ground up.

Also read: A ‘Corner-Waale Chacha’ on Bollywood’s Vanishing Villain

In sharp contrast, alternate and independent cinema has been brave in shouldering the responsibility of building cinema that shouts truth to power. With empathy at their core, the stories have been nuanced, layered and sharp. Whether it was Black Friday, Gulaal or Hazaaron Khwaeishein Aisi in the first decade of the millennium, they examined political realities without reducing them to mere backdrops for storytelling. Politics itself became a character, with protagonist’s growth dependent on how to engage with it. In the recent past, Newton, Eeb Aaley Ooo!, have used satire ably to throw into sharp relief, the oppressive realities of systems we seem to have accepted without question.

A still from ‘Eeb Aaley Ooo’.

The change through the world in mainstream cinema though, is visible. In the past three years alone, we’ve seen a spate of films that are unapologetically political. Joker examined what continued ostracisation does to a man considered and expected to struggle through survival.

Hidden Figures depicted the discrimination three talented women faced due to their race and gender. The Post, in Steven Spielberg’s inimitable style, looks at the role of journalism, the need to keep power accountable, and reinstating itself as an indelible part of democracy, from a specific incident of the Vietnam war. The most recent The Trial of Chicago 7 acutely examines the muzzling of the right to protest, an aggressive police force, and a system to bust the idea of dissent in the face of oppression. Borat 2 is about a visible contestation of a system designed to protect power, and give it impunity.

A still from ‘Borat Subsequent Moviefilm’.

Why is our popular Hindi cinema not bringing stories of landmark political realities that have changed India as we see it today? Why is it not exhibiting the ability to critique a clearly divisive, oppressive system? The ideas of politics are not diverse from who we are and the stories we wish to tell.

So instead of cinema that glorifies power and vilifies opposition, can we build stories that examine the very idea of power? Of specific incidents that have had a remarkable impact on the conscience of a nation? And all these with specific facts, and not a perspective of ‘my version vs yours’? Ideas of truth, power and politics need to return to mainstream cinema. Fearlessly.

Featured image credit: Netflix