A few days ago, I was sitting in front of my laptop with some 20-odd tabs open in what could only be described as another unimpressive day during this pandemic. Aimlessly clicking one hyperlink after another, I came across some modern art. I looked up the artist, the tag read ‘A. Twombly.’

This was the first time I came across his work, which was full of blotches, scribbles, spots of paint, and lines of crayon. Scrolling ahead, I came across an intriguing sculpture made of hemp fibres and found out that it was made by Mrinalini Mukherjee.

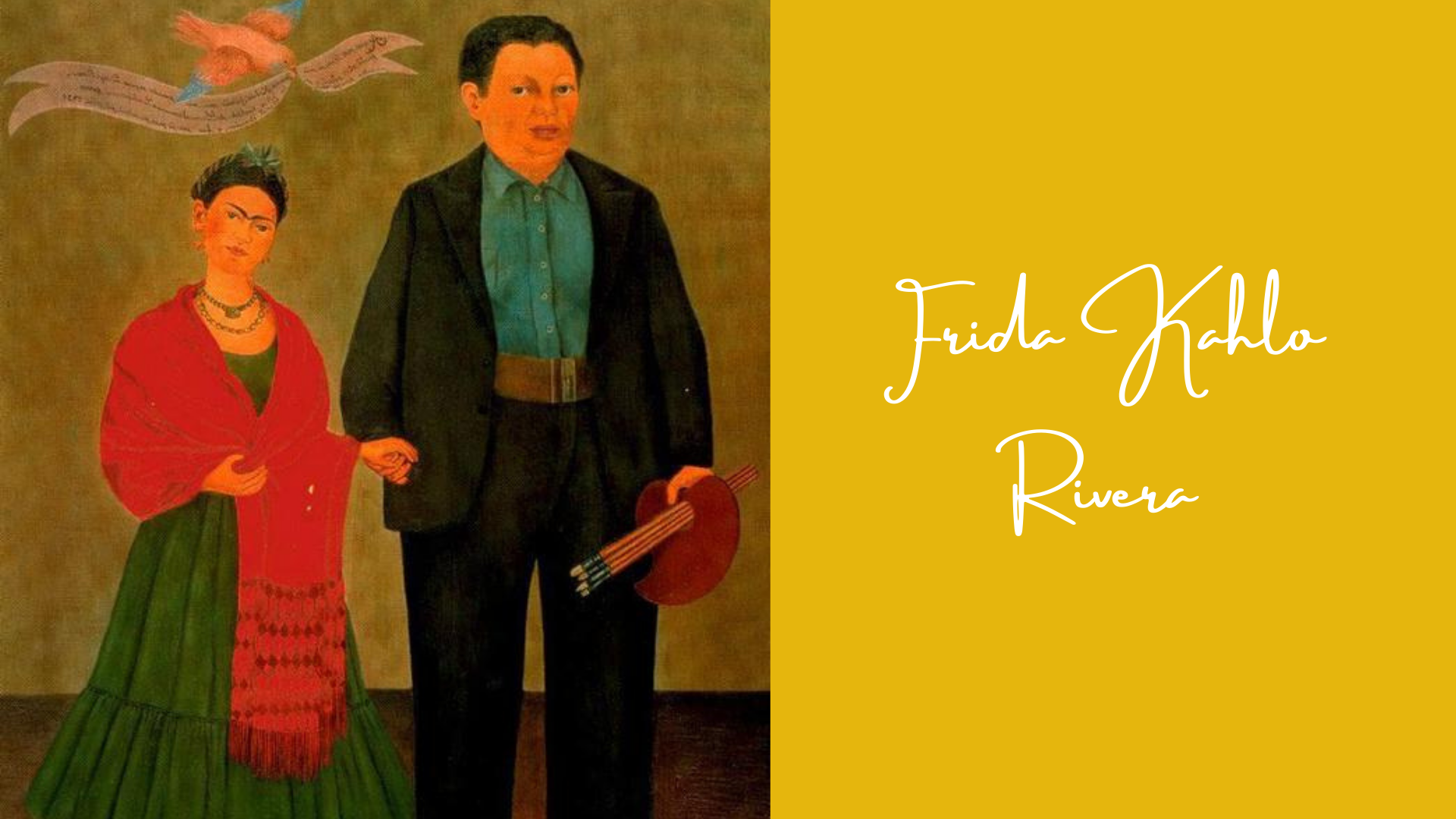

I didn’t quite catch the significance of what I had seen that day until I came across the story of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. What caught my eye here was that while the former’s works were described by acknowledging her full name, for the latter, the tag went ‘Riviera’s works…’

I couldn’t help but imagine if that was deliberate, that we called men more by their last names (I later learned that Twombly’s name wasn’t ‘A Twombly’ but Cy Twombly), and use full names for women. And yet, in what could only be described as a Keanu-Reeves-conspiracy-meme moment, more and more examples kept coming to my head. Think Darwin, but Marie Curie. Shakespeare, but Arundhati Roy. Federer, but Serena Williams. I was even more stumped with artists because the names didn’t stop: Manet, Monet, Picasso, Van Gogh, Souza, Hussain, while women artists were Bharti Kher, Dorothea Tanning, Nalini Malani and so on.

So, what was it? Did we as a society really make a choice somewhere along the way about what we call male and female professionals and artists, or was I trying to find a mountain in a molehill? You might argue that in the profession of fine art, it is your skill that makes your name and not the other way around. But that would ignore the fact that not every artist has the same opportunities and socio-economic capital to better their career. On top of that, if we’re distinguishing between male and female professionals on the basis of their names, it begs the question – does being referred only by your last name give you any benefits?

A few psychologists seem to believe so. A research paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showed through eight studies that people were more than twice as likely to call male professionals by their last names. Interestingly, the participants (men and women) showed that acknowledging someone by their last name also acknowledged a degree of fame and importance they might have against professionals (females) who were called by their full names.

Since men largely dominated socio-cultural-political spheres with their last names, it was imperative to emphasise on the full names of the female professionals (perhaps, to differentiate them from the common masses). But as we saw above, last names carried some sort of significance – something which automatically proved to be a disadvantage for women. And if you were known by your last name, the implication was treacherous for your growth. Artists Gustav Klimt and Hilma af Klint not only have very similar sounding last names but were also born in the same year, and yet no matter if we hear Klimt or Klint, our first thought goes to Gustav. Music isn’t any different – think of the fame the names Clapton, Bowie, or Presley carry, and then think of Aretha Franklin, Diana Ross and Whitney Houston.

There’s another humbug to names for women. The study noted that a reason for identifying last names with males more could be since they were more tied to their (last) name as opposed to women, who might change them over the course of their lives. Interestingly, female spouses in the art world rarely change their last names (Kahlo-Rivera, O’Keeffe-Stieglitz, Tanning-Ernst).

Names then really seem to be an agent of gender bias and inequality – inequality present in the art world, sciences, politics, sports, everywhere. Today, where movements like Black Lives Matter or #TimesUp have cried out loud that society needs to change, it’s fascinating to note that the name ‘Hashmi’ would make people remember Safdar Hashmi more than Zarina Hashmi.

Call me by my name? More like call me by my last name.

Shankar Tripathi recently completed his undergraduate studies in History and writes on issues of art and culture.

Featured image credit: Wikipedia; Illustration: LiveWire