I put the record on only to hear aircraft noise, a siren, scraps of words and a rumble in the distance. Then a male voice saying something about a “jet” and a “bomb.” I couldn’t understand much more with my poor English at the time. I was 13 years old — and disappointed. What was this? Why wasn’t I hearing a happy song, like the “We shall overcome” I’d first heard at my friend’s place? After all, that’s why I’d bought the album for five Deutschmarks at the flea market. It took a while before she finally started singing. And it took me even longer to understand the significance of this Joan Baez…

Panic attacks, Anne Frank in Baghdad and a ukulele

Joan Chandos Baez was born on January 9, 1941 in Staten Island, New York to Albert Baez, a Mexican-born physicist, and Joan Bridge, born in Scotland. She was the second of three daughters.

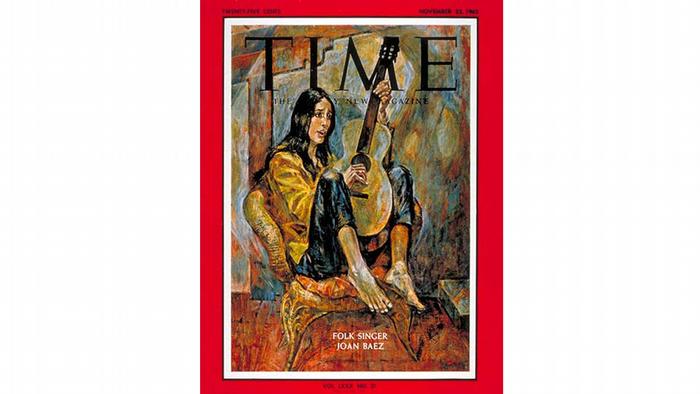

Guitar-playing “Madonna”: Time magazine cover in 1962.

Her father’s work led the family to move often; they lived on the East Coast of the US, then in Baghdad, Iraq (where the 10-year-old Joan read The Diary of Anne Frank), and later in California. Throughout her childhood and youth, Joan suffered from anxiety attacks and found it difficult to connect with her peers. Her family was her refuge.

That all changed when Joan was given a ukulele. All of a sudden, the outsider — who had been marginalised in school by the white kids because her skin was too dark, and by the Mexican kids because she couldn’t speak Spanish — found her place by playing songs in the schoolyard for the other school children.

Her first act of civil disobedience came at around that time too: She boycotted a nuclear war exercise she felt was ridiculous. From then on, she remained committed to music, and to social activism. She enjoyed being the center of attention.

To become a top singer in her school choir, she’d invent exercises to train her voice at home. A voice that Time magazine later described “as clear as air in the autumn, a vibrant, strong, untrained and thrilling soprano.”

After a three-minute sound collage — which to me, an impatient 13-year-old, seemed to go on forever — I finally got to hear the soprano: “They say that the war is done. Where are you now, my son?” I realised there probably wouldn’t be any happy folk songs on this record. It told a story I didn’t understand yet. Nevertheless, I was fascinated.

Pete Seeger and the discovery of folk music

Joan Baez also had a key experience at the age of 13. In the spring of 1954, her aunt and uncle took her to a concert by folk singer Pete Seeger. An exception in the dazzling music industry of the ’50s, Seeger stood for anti-elitist music.

“Sing with me. Sing for you. Make your own music,” he told the audience. His message was that we should forget big stars — and that everybody should be one.

Joan was electrified. She wanted to make music, and the music she wanted to make was folk. She started practicing folk songs.

In 1958, her family moved to Boston, which was at the heart of the folk revival scene. Joan studied acting, worked on the side — and got her first gig at Club 47 in Cambridge. She was paid $10, and 12 people showed up — mostly family or friends.

Barefoot and in a long dress, she accompanied herself on the guitar, an exotic beauty with a voice clear as a bell, concentrated, intense and natural. It was nothing like the often overdressed showbiz blondes of the time.

Soon more and more people wanted to hear her sing songs such as “John Riley,” “Silver Dagger” or “All My Trials.” In July 1959 she performed at the Newport Folk Festival. Her short performance was a bombshell.

Outdoing each other with superlatives, newspapers described her as the “musical Madonna” — long before the other Madonna would stir the music scene. It was the beginning of a six-decade career with more than 30 multi-award winning albums.

Joan Baez’s big dark eyes looked past me on the grainy black-and-white cover of “Where Are You Now, My Son?,” and I was a bit in love — with her eyes, her clear voice and her courage to stand up for the weak, against racial segregation and for peace. With the help of my school dictionary, I had managed to decipher the secret of the record.

Eye-to-eye with a childhood hero: The author and her favourite LP.

Anti-war and civil rights activist

The 22-minute piece, “Where Are You Now, My Son?” (one side of the album of the same name), is a unique depiction of the Vietnam War, a collage of sounds, conversations and singing accompanying the lament of a mother who has lost her son.

The sounds were recorded in Hanoi, where Joan Baez was stuck with a delegation of the peace movement around Christmas 1972. While the bombs were falling, Joan Baez was singing “Silent Night“ with the people around her.

The “Christmas Bombings” were the heaviest bombardments by the US Air Force since the Second World War. Baez later wrote in her memoir, And a Voice to Sing With, that the album “is my gift to the Vietnamese people, and my prayer of thanks for being alive.”

When the album was released in 1973, Joan Baez was 31 and a world star. Her performance at the Newport Folk Festival in 1959 had launched her meteoric career. Many of her records went gold. She was onstage at the legendary Woodstock Festival in 1969 and also made Bob Dylan and his songs world famous (“Forever Young” is one of them). Those were just a few of her musical achievements.

Inseparable from Joan Baez’ music was her political activism: In 1963, she marched side by side with Martin Luther King against racial segregation. She was later arrested during protests against the Vietnam War.

In 1966, right in the middle of the Cold War, she was invited to perform in East Germany on May 1, International Workers’ Day. Rather than serving as the poster child of Communist authorities, she had dissident songwriter Wolf Biermann join her unannounced onstage at the East Berlin cabaret, Distel.

The state had already blacklisted and banned Biermann from performing publicly. But Baez wouldn’t toe any ideological line: She opposed oppression, whether from the right or the left. The concert was filmed for East German television but never broadcast.

If there’s one surprising thing in her career, it’s that she wasn’t inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame until 2017.

Joan Baez is inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Hall in 2017.

Farewell tour

July 2019, exactly 40 years after I had bought “Where Are You Now, My Son?” at a flea market, I saw Joan Baez appear on a sparsely lit stage singing “Farewell Angelina.” It was her farewell tour. Around 3,500 people had come to the small island of Grafenwerth in western Germany to experience the great lady of folk live again. The bell-bright soprano had become a sonorous alto. It was thanks to Joan Baez and Bob Dylan that I had loved to learn English and become interested in politics and history. She was a role mode who led me to develop my political thought. Thanks for that. Happy birthday, Joan Baez!

Featured image: Baez performa at the 32nd Annual Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony in New York City in April 2017. Photo: Reuters/Lucas Jackson

(DW)