While Daft Punk’s break-up may have been unexpected, the enigmatic nature in how the public were notified was predictable. Announced via the electronic duo’s YouTube channel, an upload titled ‘Epilogue’ turned out to be a scene lifted from their 2006 Electroma film, alongside a vocal borrowed from a track on 2013’s ‘Random Access Memories’ album.

The pivotal desert scene features a prolonged trek by the duo in their instantly recognisable helmets and culminates in one self-destructing while the other walks away. Continuing then what is the pair’s time-honoured preference for ambiguity, it indicates a finale while refraining from disclosing the explicit details.

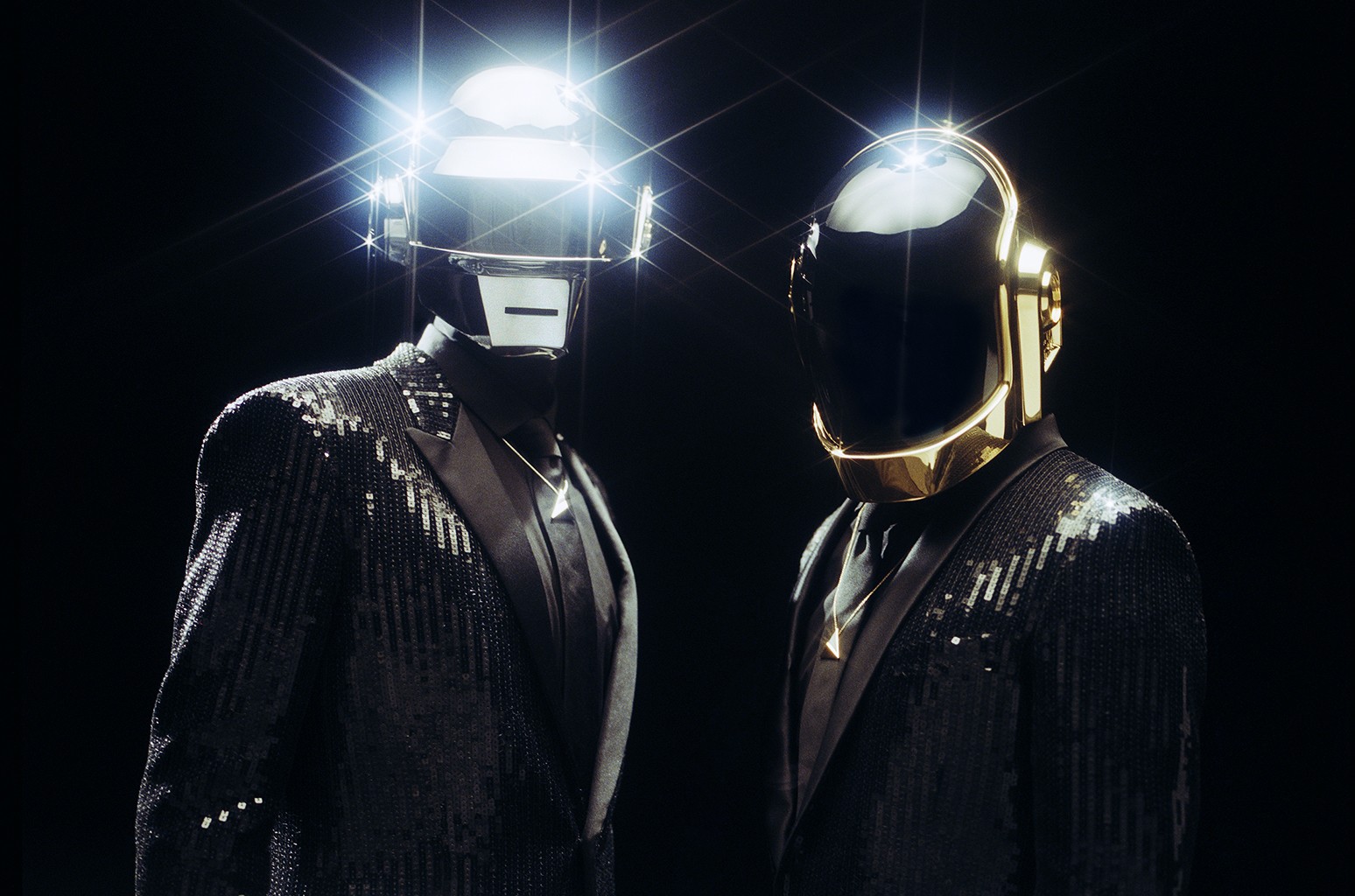

Over the past 28 years, Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo (the men behind the helmets) developed a complex and counterintuitive communication strategy. It was an approach that saw the pair hiding behind their alter-egos but going on to conquer the world of electronic music at the same time.

As the more vocal of the two, Bangalter has indicated that this method was fundamental to Daft Punk’s self-preservation. “If you can stay protected and get noticed then it’s all good”, he told journalist Suzanne Ely in 2006. What began with Bangalter and de Homem-Christo using various masks to hide their discomfort within photoshoots – obscuring rather than projecting a specific image – was eventually resolved when they reinvented themselves as androids.

Robot rock

Like the electronic group Kraftwerk before them, these cyborgs further celebrated the electronic, automated characteristics of their music, while at the same time orchestrated a mythology in conjunction with technology’s all-pervasive influence.

Bangalter even presented an origins story in which he claimed that the duo’s appearance was the result of an accident. Specifically, that the explosion of an electronic music sampler in 1999 had transformed them into their robot alter egos. Yet alongside this superhero version, Daft Punk also cited the conversion as being their response to fame.

“We don’t believe in the star system,” Bangalter stated. “We want the focus to be on the music. If we have to create an image, it must be an artificial image. That combination hides our physicality and also shows our view of the star system. It is not a compromise.”

Anti-celebrity superstars

In this sense, I believe Daft Punk have become an example of an “anti-celebrity celebrity”. Yet despite what they might have claimed, with arena tours and cameos in Disney movies, Bangalter and de Homem-Christo were far from being “anonymous”.

Theirs was a stance fraught with contradiction – and one maybe familiar to many working in arts and culture who find their rejection of consumer culture operating within the same market-driven constraints. In Daft Punk’s case, it resulted in often uneasy relationships such as the robots’ involvement in global advertising campaigns, and many Daft Punk interviews issued by media outlets that repeatedly assured us that they rarely give interviews.

The pair’s press engagement has been particularly cultivated to maintain this “media reluctance” narrative. And it became a mutually beneficial arrangement, perpetuating Daft Punk’s anti-stardom position while also enabling publications to claim they had an exclusive.

Got lucky?

For an audience that may similarly be suspicious of media saturation – and what it can indicate in terms of “selling out” – this notion of Daft Punk’s interaction being rare, intimate and indifferent to the supposed demands of industry may also have been attractive.

Perhaps French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu had it right when he said that profits can be derived from “disinterestedness”. Indeed Daft Punk’s marketing succeeded because of its highlighted rejection of the most obvious, unromantic mechanisms of commerce.

The ‘Epilogue’ video message is then a fitting end, highlighting remoteness and attachment, anonymity and familiarity, and all delivered by a self-destructing robot with no accompanying press release. It aptly concludes Daft Punk’s legacy of technology-assisted public engagement. Over and out.

Daniel Cookney, Lecturer in Graphic Design, University of Salford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Featured image: Billboard.com