This is the fourth article of a five-part series. Read the first here, the second here, and the third here.

For every woman in correspondence with Delhi, Delhi is the city of Nirbhaya. When unfamiliar, it is laden with an expectation of brutality. When familiar, you carry an overwhelming inkling of brutality trailing you. As a woman in Delhi, your body is always under surveillance – by the leering eyes of men, by the grating eyes of women, by the commanding eyes of the State, and mostly by the instinct within you.

When Ishani first moved to Delhi, her parents asked her to be careful. “You don’t need to attract attention to yourself,” they said. To not attract attention in a city where it is equivalent to existing would have meant tethering herself to an inside space. Ishani says, “I wanted to attend classes, but I also always wanted to be out and about to see the city and loiter around.”

Ishani grew up in a town, she says, that no one in Delhi she has met had heard of. She is from Jagiroad in Assam, a small town known for its paper industry. “In Jagiroad the skies were vast. I remember during the summer vacations I used to go to a friend’s house every day and it was a beautiful road. There were large patches of the sky running along fields of newly sown rice paddy,” she tells me. She’s an aesthete, she is sketching with her words.

When I ask her if she could share her impression of Jagiroad, she says, “I don’t really sketch Jagiroad. I like sketching places I capture myself. There, at most, I go to my roof.”

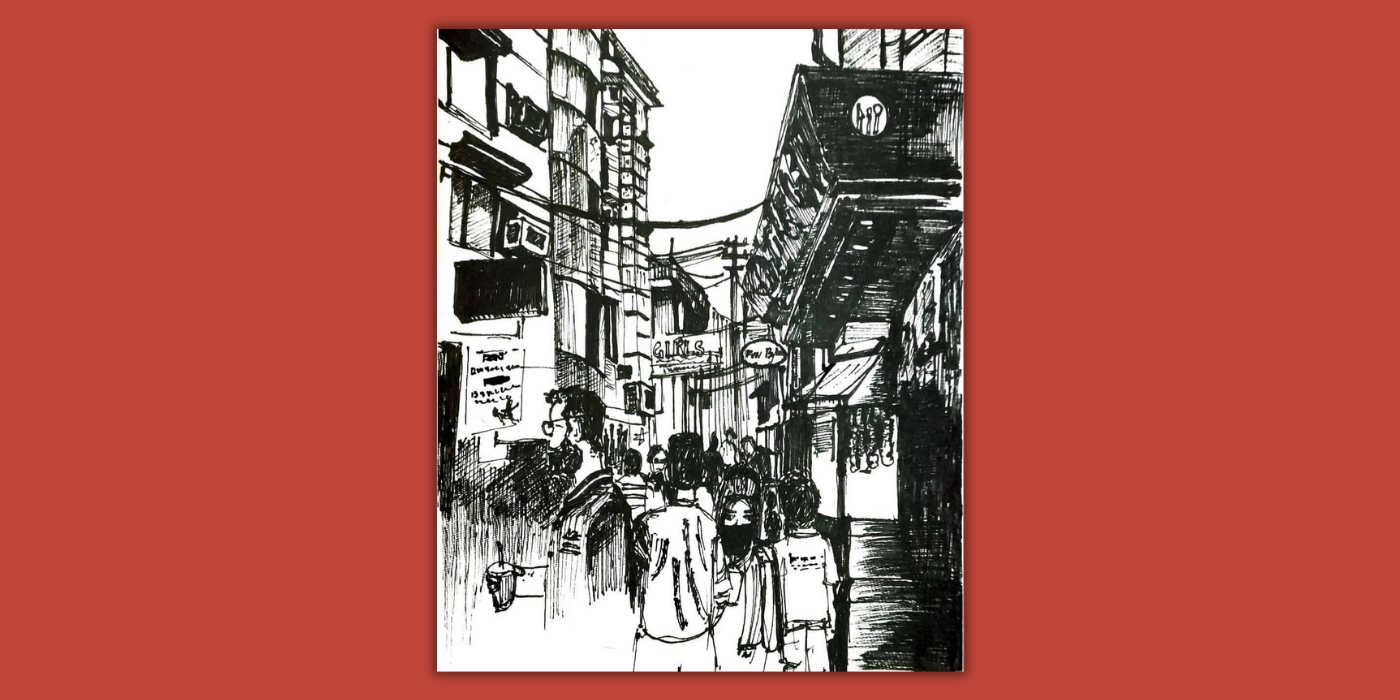

It is not with her own set of eyes that she sees Jagiroad, she sees it from the roof of her house which is like a prison with a view. Instead, on a cramped piece of paper, there’s a detailed view of the Kamala Nagar market, where students from Delhi University’s north campus flock. “I spent so much time walking in Kamla Nagar. I loved walking, observing the places, the people who often came,” Ishani recalls, with a sense of peace.

Women in Delhi live between enslavement and liberation – two contradictory realities. In every lane, each woman defines how much her version of liberation will be enslaved by fear. Despite the connotations associated with Delhi, Ishani reflects and says, “I think I felt more autonomous in Delhi.” Thinking further, she adds, “Sadly, the discomfort of a solitary woman walking through the streets was not geographically specific to me.”

Now, pushed back to living at Jagiroad because of the lockdown, Ishani recalls Delhi with fondness. “I minimise myself here in Jagiroad. It is like I am two different people here and there.”

Ishani looks at walking as a matter of belonging. A woman’s need to walk through a city alone almost seems rooted in a sense of catharsis, a sense of purgation from the monotonous jibes of daily life. When Ishani was living in Delhi, she says, walking around Kamla Nagar was one of the ways in which she dealt with her mental health. She says, “I think the aspect of actively occupying space gave me agency. I walked. I slowly plotted the place in my mind – this is the shop you get hoops for dreamcatchers, this is the shop where you have to come when you need to buy groceries and so on. Walking in the city brought me closer to the self I wanted to be – independent. I wasn’t relying on a brother or father to get me something. I had some power when it came to transactions.”

Also read: Sauntering Through the City Streets: What It Means to Be a (Female) Flâneur in Delhi

Her life in Delhi gave her the force to understand who she was. At Jagiroad, she tells me, she doesn’t really go out much. She says there is no specific reason for her to go out and most chores that require her to walk are handled by the men in the house. In their book, Why Loiter, Sameera Khan, Shilpa Phadke, and Shilpa Ranade write,

“While women often record feeling physically safer in their own neighbourhoods, which are known to them and where they are known, this does not, however, translate into increased access to public space. In fact, spaces in which women are recognised as wives, daughters, and sisters are often the most restrictive.”

In Jagiroad, Ishani says, she doesn’t really feel at home. “Here, I have to ask for permission. I have to discuss where I will be going, so I let it be. Ideally, I want the freedom to put on my chappals, and walk away.”

Long before Ishani started walking on the streets of Delhi, her comfort with Delhi’s public spaces came because of the metro. “I came of age when I took the metro for the first time. Experiencing Delhi was overwhelming and not in a bad way,” she says. The Delhi Metro has always had a precarious relationship with women. Starting from seats reserved for ladies, the front coaches reserved for women, and the proposal to make the metro entirely free from women often invites criticism from the club of patriarchal subjugation. Many have spoken of how public transport is essential to provide women opportunities and economic independence.

Almost always, arguments around women accessing public spaces are often rooted in women accessing public spaces with a purpose. However, to many like Ishani, it is also necessary with the purpose of flanerie – of just walking around and loitering without any purpose, to be in a public space to just belong. And it is perhaps with this in mind that Why Loiter argues,

“…we need to redefine our understanding of violence in relation to public space — to see not sexual assault, but the denial of access to public space as the worst possible outcome for women. Instead of safety, what women would then seek is the right to take risks, for it is only by claiming the right to risk that we can truly claim citizenship.”

They do so with the cognizance that in popular perception, “…a loitering woman is up to no good. She is either bad or dangerous to society.”

Living in a city on her own gave Ishani the opportunity to walk. Even though in her class in college, there were always folks from the city whose lives she could never relate to, her walking always came to her rescue. “Sometimes my friends who were Delhiites depended on me for directions. The idea of fully inhabiting a city made me very happy, very alive.”

Spoilt by the freedom of Delhi’s streets, and away from the city where she made herself coherent, she says, “I constantly feel this in-betweenness now, the sense of neither being here nor there. It’s like I am always in transit.”

With this feeling of transit, she thinks often of walking and of Delhi’s density. When I ask Ishani what kind of chappals are her favourite, she says, “If not for the weather, simple slip ons – ballerinas, the ones which you easily slide your toes in.”

The ease of the chappal is a metonym – of the ease of walking off into a consistently expanding and contracting world.

Muskan Nagpal is an English Literature graduate and a Young India Fellow.

Featured image credit: Ishani Ahmed Saikia/Editing: LiveWire