The recent case of a teenage girl who was prohibited from entering an examination hall has led to heated debates on questions of culture and decorum in the Assamese public sphere. A 19-year-old girl was asked to drape a curtain in an exam centre to cover her legs because shorts were seen as an inappropriate dress code.

The incident took place in Tezpur, a historic town in Assam. It is the birthplace of Assam’s first filmmaker, Jyoti Prasad Agarwala. While Agarwala is a celebrated name in the state (and rightfully so), not many know the price that the actress who played the lead role in his movie had to pay. Aideu Handique, who played the titular role in the first Assamese feature film Joymoti was socially ostracised. Her only crime was that she acted in a film with men and participated in the public sphere. Handique – the first woman film actor from Assam – didn’t marry, but this was not out of her own choice. She was not seen as a ‘respectable’ woman.

While the shorts incident is only a few days old, these debates on questions of attire and culture are not new to the state. The city of Tezpur is home to the Northeast’s premier university Tezpur Central University, which is known for its strict dress code. In fact, in many schools run by the state government, girls are asked to wear mekhela sadors (a form of traditional Assamese attire) from Class 8 onwards. In some schools, there has been a certain change as now they ‘allow’ girls to wear shirts and skirts till Class 10. However, in most schools, they have to wear mekhela sador in Classes 11 and 12. The boys, however, can wear trousers and shirts irrespective of their class.

Not surprisingly, girls and women at large are seen as protectors of tradition and culture. In Assam, many colleges, universities and even offices have a strict dress code for women. They are expected to wear mekhela sadors and/or sarees.

Ideas of gender and sexuality have always shared a close relationship with labour, be it in terms of the sexual division of labour or unequal pay. Apart from the economic aspects of this relationship, the clothes that a woman wears become another important determinant of her labour and social position. What a woman wears is a signifier of her respectability in society. Thus, the often repeated argument in social media and television during the ‘half-pant’ incident in Assam – if I were her parent/guardian, I would not let her go to the exam centre in shorts – blamed her parents for not being able to inculcate the values of respectability and decorum in the girl. Since the parents were seen as ‘incapable’ of doing so, the society and social media took it upon themselves to moral police the girl.

Any deviance from the set dress code can invite all kinds of measures – from punishment to social humiliation. Both of us have grown up hearing about such cases and their absolute normalisation in society.

Also read: Schools Need to Stop Shaming Girls for the Length of Their Skirts

Bidisha* was only 20 years old when she was interning in a microfinance office in Guwahati. On her first day, she wore a formal skirt and shirt like most people in corporate offices do. In response, she was asked by one of her female workers to not wear skirts to workplaces. Similarly, Banani*, a young research scholar, who had started teaching in a college in Guwahati, was asked not to wear a kurta to the workplace because female teachers should only wear sari or mekhela sador. In fact, when certain workplaces in Assam ‘allow’ women to wear kurta and salwar kameez, they are seen as ‘progressive’.

Women often discuss how they are not taken seriously if they are dressed in shorts, skirts, trousers or dresses. To be taken seriously in their job, they have to dress in a ‘respectable’ manner – that is, wearing saree, mekhela sador and salwar kameez. While certain workplaces are more ‘liberal’ and ‘allow’ women to wear kurta and salwar kameez, during special occasions, they ask their women employees to wear sarees and mekhela sador. In these university and college settings, women employees would be expected to wear sarees and mekhela sador on occasions like freshers, farewell, inspections, seminars, etc.

In recent times, humiliation also includes brutal trolling in social media. It is often in the name of ‘protecting’ culture that many of these incidents take place. Women most often become the target of this gatekeeping of culture. The harassment and trauma that Bidisha and Banani have faced are the same. It is just that social media makes certain incidents viral and adds the element of public shame and humiliation to them.

Otherwise, women have been policed to dress in particular ways from much before. In fact, many women also comply because dressing in the desirable manner as decided by society makes it easier for them to access public spaces. Thus, although these issues of how clothes and dressing style affect women’s position in society are not new, social media has given them a new visibility and dimension. It is no longer only institutions that enforce dress codes but also the internet. The moral police are now everywhere in the form of trolls.

*names changed

Rituparna Patgiri teaches Sociology at Indraprastha College for Women (IPCW), University of Delhi. Ritwika Patgiri is a PhD student in the Faculty of Economics, South Asian University (SAU), New Delhi.

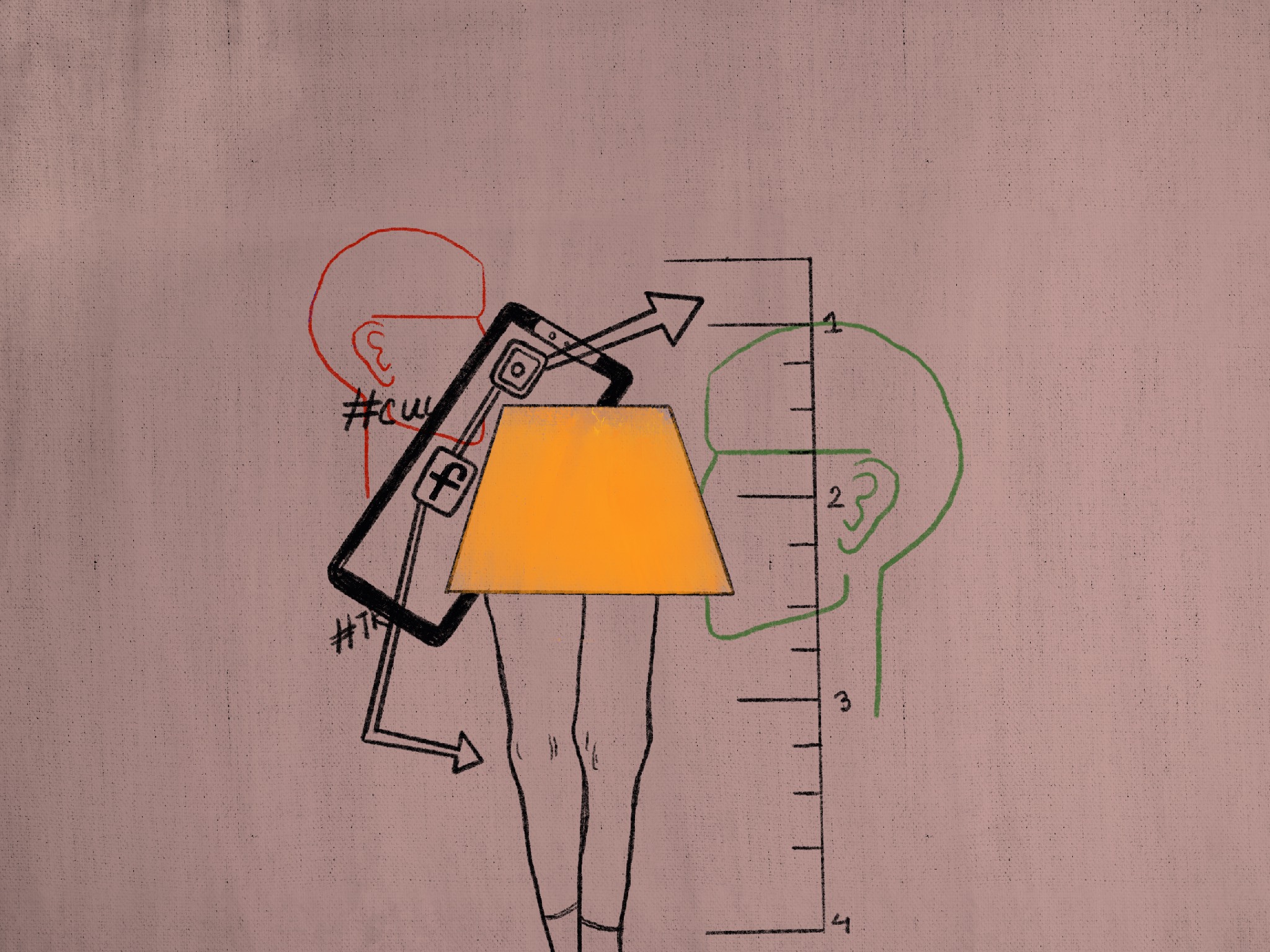

Featured image credit: Pariplab Chakraborty