Death has always been shrouded in an overwhelming eerie presence for me. Frightening and inevitable, I imagine Death in its traditional black garb knocking, uninvited; emitting a waft of chill in the rooms it decides to visit. Diminishing life into merely a struggling bird with broken wings, it laughs at our feeble attempts to fly.

But for the greatest Welsh poet of all the time, death is both the destroyer of life as we know it and the means to extend it. Dylan Thomas (1914-1953), famous for his acute use of lyricism and imagery in his poems, extended the literary tradition of Romanticism through his poetry which promoted subjectivity, nature and imagination.

Thomas, though a poet writing in the 20th century alongside other prominent modern poets, such as T. S. Eliot, W.H. Auden, and Stephen Spender, decided to brush his poems with soft quick strokes to give a smooth edge creating the illusion of movement. His poems, unlike the modernism theme of disillusionment and alienation, gave a sense of hope to people who needed it during the 20th century.

Life, for Thomas, does not end with the onset of death but traces of the real self lives mingled with nature. A time comes in life when you start getting older when your body doesn’t feel the same. When your youthful ways don’t suit you anymore, your rosy continence and youthful vigour fail you. Death feels like a dreadful reality; inevitably looming large.

For me, death has always been a dominating presence, inevitable but inexplicable. It accompanies a sense of loss and numbness that the world experienced together with the coronavirus. Thomas’s view on death and life is a poignant response and perhaps a means of solace for the world right now.

Remembered for his seminal poem, ‘Do Not Go Gentle Into the Good Night’, where he accepts the righteousness of death and its place in the cycle of life, yet he implores to “rage rage against the dying of the light” (death). Thomas’s poems are full of images of creation and destruction, life and death, and the connection between man and the universe.

Thomas explores the dichotomous quality of life: it is both reproductive and destructive. For Thomas, life contains the seed of its own destruction; after all, the only certainty in life is death. Death, as an extension of life; life, an inevitable death. Time is both the ally and the adversary. It introduces you to the wonder of nature and life while slowly slithering you towards old age and eventually death.

“The force that through the green fuse drives the flower

drives my green age; that blasts the roots of the tree

is my destroyer”

(The Force That Through The Green Fuse).

Also read: For the Love of Clouds: Verses in the Sky

Thomas was by no means the first poet to pick this duality of life. Blake and Wordsworth have explored it before him. But Thomas’s use of provocative lyricism and emotive imagery makes us appreciate the wonderment of life and dread the inevitable realisation of its shortness. The dread of losing consciousness and moving forward in life yet again takes you closer to that darkness.

Thomas’s bleak view on life – being both regenerative and destructive – can easily push us over the precipice of existential dread. But it is nature and the universe itself which cradles us when we cross over to the other side. Thomas’s answer to the dichotomy of life is to understand the presence of life, even after death, in nature. For him, human life and nature are intricately interconnected.

“This flesh you break, this blood you let….

Were oat and grape

…My wine you drink, my bread you snap”

The same life flows through nature and humankind.

Scientifically, we all exist within the all-encompassing universe that is closed. It contains all beings which remain dependent on each other to complete the cycle of life. But even after the ultimate end, the essence or light of life stays behind. For Thomas, this light of life mingles with the energy of nature.

“With the man in the wind and the west moon;

When their bones are picked clean and the clean bones gone,

They shall have stars at elbow and foot;

Though they go mad they shall be sane,

Though they sink through the sea they shall rise again;

Though lovers be lost love shall not;

And death shall have no dominion.”

(Death Shall Have No Dominion)

Thomas’s poetry offers comfort by using images that are almost religious, exploring the mystic aspect of life. For me, Thomas’s poetry not only leaves behind hope for the eternal presence of self in the world but also explains the force of nostalgia I feel whenever I look at the wonders of nature. The clear night sky bejewelled with stars, the sway of trees and the mist in the air, the raucous birds pecking softly in the trees. Perhaps the essence in me recognises the kindred light around me, calling me softly to recognise it and to rejoice in the unity of the universe.

Varsha Sundriyal is a literature enthusiast and a budding writer.

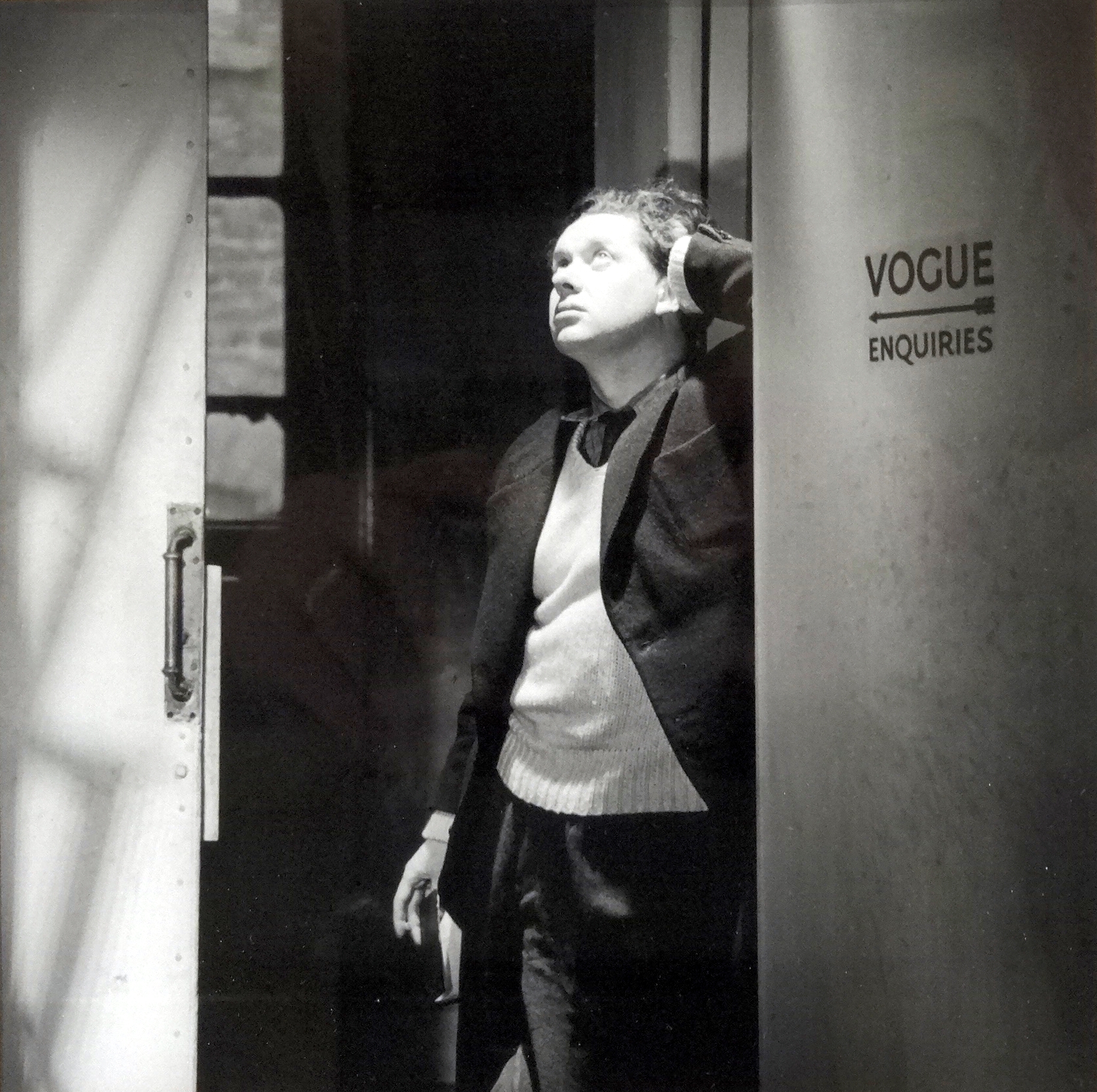

Featured image: Dylan Thomas Museum in Swansea; Credit: Flickr/Jim Forest