‘Male authors of the world’s patriarchal epics blame

The bewitching femme fatales who seem bereft of shame

But the heroes insist they need such beauties as their brides

In the killing fields and theatres of war, like trophies by their sides.’

– ‘Sita and the Golden Deer’

One can hardly be convinced of the wealth, fluency and dexterity of sarcasm until one arrives at the poetry of Sanjukta Dasgupta. Linear, measured, suave and highly dissident, Dasgupta’s poems stand out for their remarkable ability to compress social criticism in bold and geometrically precise sarcastic strokes. Keki Daruwalla calls her poems “trigger-tense poetry at its best” and one would be hard put to challenge the observation.

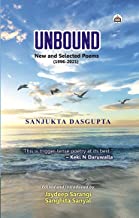

Unbound: New and Selected Poems (1996-2021)

Sanjukta Dasgupta/Edited by Jaydeep Sarangi and Sanghita Sanyal

Authorspress, 2021

Unbound: New and Selected Poems (1996-2021) is Dasgupta’s seventh book of poems that, along with her new pieces, brings together the best of her work from her six former collections. There is a wide range of subjects here – poetry, the pandemic, memory, history, love, loss, negotiation, social injustice, nature’s bounty and more. What, however, strikes the reader with particular force in most of these poems is their consistent articulation of the woman question – women’s socio-cultural status, identity, historical and ideological stereotyping, ways of rebellion, and possibilities of emancipation.

In Dasgupta’s poetry, there is no obliqueness or ambiguity, no dilly-dallying with metaphor, no laboured linguistic games. As a feminist scholar and critic, her terrain is clearly political and her focus, pre-eminently, on her ideas. Her feminism too, one realises, has a wide intersectional base. From mythological and fictional women across ages and cultures to everyday women of all ages and classes in homes, kitchens, workplaces and dreams – Dasgupta converses with all.

In ‘To Avantisundari’, she speaks to the 9th century Prakrit poet, wife of scholar-dramatist Rajshekhar – “Your footsteps unseen/ Provoke, tantalize./ Till a sister ten centuries young/ Continues what you, incomparable Avantisundari,/ Began” – establishing a communion between her and the vernacular women writers of nineteenth century India.

‘In Memoriam’ is a tribute to the socialite Naina Sahni who was murdered in 1995 and her dead body burnt in a tandoori oven – “Did you not see your tragedy on their brows?/ Powerless Circe, futile Urvasi,/ Did you take it too easy, alas?”

In ‘Mrinal’s First Letter’, the poet focuses on Mrinal, the protagonist of Tagore’s famed feminist short story ‘Streer Patra’ (‘The Wife’s Letter’) – “Mrinal like her elder sister Nora/ In a faraway world/ Shut herself out from the hypnotic/ Humiliating, terrifying sacred space”. Sita, Kali, Durga, Manasha, Meera, Saraswati, Chandalika, Chitrangada, Circe, Medusa, Radha, Helen, Draupadi, Eve – all wander freely across Dasgupta’s poetic canvas in a tight, empathetic bond of sisterhood, voicing and reinforcing each other’s stories as they open their arms to embrace women globally.

However, the figure that watermarks Dasgupta’s feminist oeuvre with the greatest potency is Lakshmi. Lakshmi, or Lokkhi in Bengal, is not merely the goddess of wealth and good luck but also a powerful cultural trope of the patriarchal stereotyping of women. The Bengali word ‘lokkhi’ has several connotations – good, tranquil, pure, auspicious, benevolent. While as an adjective, it can be and is often applied irrespective of gender, for centuries, its use has been typically reserved for women.

Also read: On Writing Like a Woman: A Review of Paul Kaur’s ‘The Wild Weed’

The ideal girl/woman scripted by patriarchy is the ‘lokkhi meye’ – shy, quiet, docile, dutiful and sacrificing. Dasgupta rightly compares this construct of the ‘lokkhi meye’ or Lakshmi to the Victorian idea of the ‘Angel in the House’. Implicated in the idea of ‘lokkhi’ are also, as Dasgupta clearly points out, biases of caste and class as only high-born women of the upper class could aspire to this ideal. Thus, in the poem ‘Gora’s Re-birth’ based on Tagore’s novel Gora, Gora’s realisation that the maid “Lachhmia and the rarefied Lakshmi/ Are indissolubly entwined” remains, in its egalitarian spirit, revolutionary even today.

Dasgupta’s ‘Lakshmi’ is critical of her status from the very beginning. In ‘Lakshmi’, she is deafened by prayers – “Give us more, more, more/ More than another/ Give me more, mother/ More than everyone else”. “The anthem,” she realises, “is the same everywhere” and regrets having to, immortally, listen to it. In ‘Lakshmi Unbound: A Soliloquy’, Dasgupta’s Lakshmi resents her enforced docility and domesticity:

‘I just can’t be Lakshmi

I have to break the silence

My wealth is not jewels

My wealth is my gypsy spirit’

Rebelling against patriarchal imposition, Lakshmi seizes her feminist binary – “I don’t want to be Lakshmi/ I am Alakshmi/ Trap me if you can!” Alakshmi or Olokkhi in Bengali is Lokkhi’s binary opposite – loud, unruly, wilful, inauspicious. Alakshmi is Lakshmi unbound from her fetters of enforced domesticity, patriarchal expectation and self-abnegation. She is Dasgupta’s defiant feminist who refuses to be scripted, hedged and spoken for by patriarchy, capitalism or consumerism. Asserting her control over her body, mind and tongue, Alakshmi advocates a strong earth-centric ethic as she walks free into possibility and promise.

In ‘Sita Meets Lakshmi’, Dasgupta attempts a radical feminist reading of the Ramayana with the golden deer symbolised as Alakshmi or Lakshmi Unbound. Drawn to the deer, Sita steps out of the lakshmanrekha to claim her freedom – “Sita felt Lakshmi’s firm clasp/ As her chains clattered to the ground!” Given that Sita is widely believed to be the incarnation of Goddess Lakshmi, her association with Lakshmi Unbound is also an attempt to reclaim her authentic identity as a free woman.

To focus on Dasgupta’s strong feminist leanings is not to deny the wide thematic and emotional range of Unbound. The 135 poems in this powerful collection constitute a bold social commentary on the hypocrisy, fanaticism and decadent morality of our times with a firm faith in the redemptive power of poetry. However, what lingers in our minds long after it has been read is its staunch avowal of an empowered pan-cultural sisterhood.

Basudhara Roy teaches English at Karim City College affiliated to Kolhan University, Chaibasa. Her latest work is featured in LiveWire, The Woman Inc., Madras Courier, Lucy Writers Platform, Berfrois, The Aleph Review and Yearbook of Indian English Poetry 2020-21, among others. She is the author of two collection of poems. Her third collection Inhabiting is forthcoming this year. She loves, rebels, writes and reviews from Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India.

Featured image: Nikunj Gupta/Unsplash