Netflix’s recently released first quarter earnings for 2022 reported a shocking loss of 200,000 subscribers – a worrying shift for a business that had previously only seen sustained growth since 2011.

The New York Times headline ‘Netflix loses subscribers for the first time in a decade‘ was catchy – however, a little bit of nuance is required. The company’s withdrawal from Russia as a response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and related sanctions saw a loss of 700,000 subscribers attributed to the quarter.

The net result, taking into account the Russian loss, was a growth of 500,000 subscribers – a number still short of the expected growth of 2.5 million subscribers.

Far worse in the report was Netflix’s estimation of a further 2 million subscribers to be lost by the second quarter.

As a result, Netflix signalled cutbacks in content expenditure, cancelling the Bright sequel and comic adaptation Bone, and flagged potential cuts to employee numbers and discretionary spending.

So what has caused this loss and where does Netflix go next?

Platform proliferation

Netflix is increasingly challenged by a streaming landscape populated with a growing number of platforms – a fact the company recognised in their letter to shareholders. Referring to the robust competition from other players, the company noted:

over the last three years, as traditional entertainment companies realised streaming is the future, many new streaming services have also launched.

The launches of Disney+ in 2019, HBO Max in 2020, and Paramount+ in 2021 has seen these US-based entertainment companies step into streaming. There are a growing number of players in the market. Every major studio that launches a platform means less content Netflix can distribute – when the major studios launch they remove their content from Netflix.

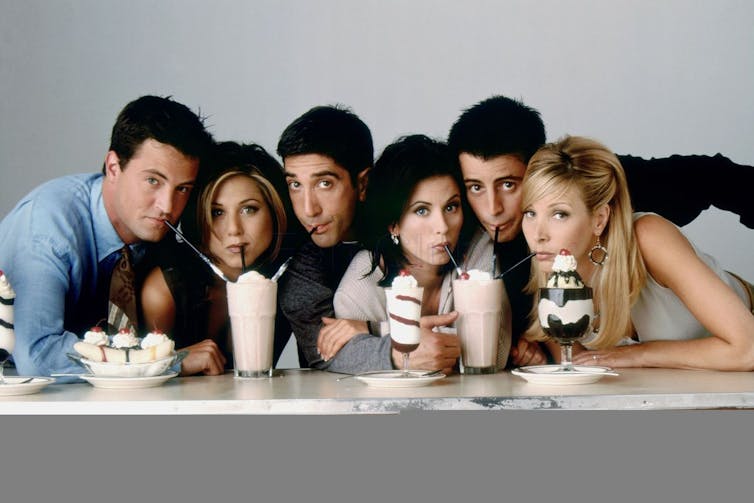

The Netflix license for Friends – once one of Netflix’s top watched shows – was not renewed by rights holder Warner Brothers Television in 2020. As a result, Friends is disappearing from Netflix markets around the world, instead streaming on Warner Brothers’ Discovery platform, HBO Max.

Friends was one of the most popular licensed shows on Netflix, but is now exclusive to streaming service HBO Max. Photo: IMDB

Global streaming platforms have also made inroads with popular originals. Severance on Apple TV+, Halo on Paramount+, and Raised by Wolves on HBO Max have all been popular with audiences. This success is no doubt forcing a more savvy approach from consumers increasingly hit with the reality of high monthly bills when paying for all services.

Netflix and others are also competing for attention with local Subscription Video-on-Demand (SVOD) services, like Stan in Australia and Blim in Mexico, and regional services, like Viaplay in Northern Europe and VIU in Asia.

These services hold unique value propositions in their markets and often trade upon pre-existing relationships in local media ecosystems. Viaplay has a long history as a satellite television network in Sweden while Stan is a venture of local Australian free-to-air broadcaster Nine Network.

It is becoming increasingly difficult for global streaming companies like Netflix to compete against not just other global media companies, but also compete with local and regional services as well that have deeper ingrained relationships with audiences.

Why Netflix needs subscriptions

How can a drop of only 200,000 subscribers from a total of 220 million subscribers crash a share price by 35% and instil fear across the broader streaming sector?

Netflix is a pureplay SVOD service and they are relatively unique in the marketplace. They focus on a single product and delivery method – subscription television. In their 2021 annual report, Netflix said 99.4% of all revenues came from subscription fees (a paltry 0.6% came from the dying DVD business).

Given the uniqueness in the market of this pureplay focus, streaming scholar Amanda D. Lotz termed Netflix “a zebra amongst horses” to describe the company’s relationship to other SVOD services.

Almost every competitor of Netflix has another aspect to their business. In her 2022 book Netflix and Streaming Video, Lotz refers to the SVOD component of Disney for example as a “corporate extension” of the underlying media business and of Apple TV+ as a “corporate complement” to their technology business.

For companies like Disney, the SVOD service can leverage and cross-subsidise the broader business. Apple TV+ itself is under little to no pressure to turn a profit, as Apple’s major growth driver is the iPhone.

But for Netflix, all of the eggs are in the same basket. Even small changes to subscriber numbers, and certainly a negative growth outlook, forces a conceptualisation of their future, without other business areas that can offset these losses.

Indeed, that is partly why Netflix has been making inroads into other businesses, through the acquisitions of Scanline VFX, a visual effects company in 2021, and Boss Fight Entertainment, a gaming company in 2022. We can expect some greater urgency across these acquisitions.

What’s next for Netflix?

Netflix is proposing two key measures to alter the negative subscriber trajectory – a lower cost, ad-supported subscription tier and a crackdown on password sharing between households.

Neither of these suggestions does anything to offer a reason to stay subscribed. There is no promise enjoyable original series won’t be cancelled too soon, like Sense8, Altered Carbon, or The OA for example. Rather than adding new features or content, the Netflix answer is removing key cornerstones of the service.

For Netflix, its recent subscriber loss could warn of a less promising future.

Oliver Eklund, PhD Candidate in Media and Communication, Queensland University of Technology

Featured image: DCL “650”/Unsplash

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.