In his book Maximum City, author Suketu Mehta contends that, “Each Bombayite inhabits his own Bombay,” attributing something more than geography to the heart of this city.

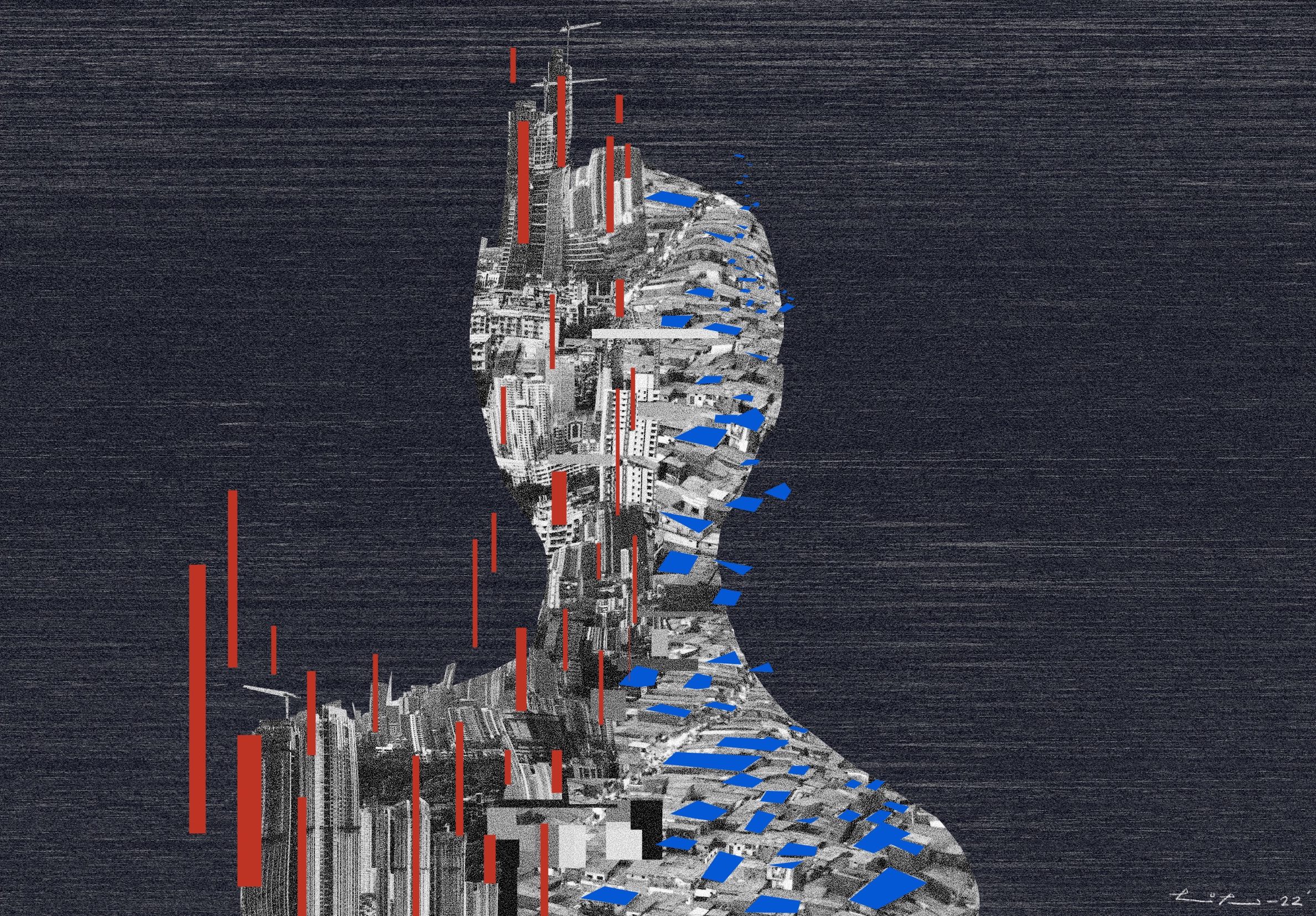

Growing up, I did not understand the dichotomy of this magnanimous metropolis. My elementary school teachers would always describe it as ‘diverse’ and ‘cosmopolitan.’ “A City of Dreams,” they would say. And while these adjectives are mostly accurate, they are also shields, protecting the city, and its citizens, from facing unpleasant, yet urgent truths. No two people have lived in the same Mumbai because no two people can live in the same Mumbai. There exist two figurative cities within this single piece of land. And somewhere between the tallest building and the dingiest room in a slum, these worlds collide, silently enough to not shatter, but never managing to bridge the chasm between them.

There is, of course, one version of this city that presents itself as an urban maze of high-rise buildings and modernity. This Mumbai glistens in the night sky as its endless skyline projects bright lights into the darkness, replacing the twinkling stars hidden beyond the pollution. The roads here are never empty, constantly pervaded by people in a rush – honking, stopping, speeding, soaring. They are decked with seven-storey malls and aesthetic coffee shops and fine dining restaurants.

But beneath the glitz and the glamour of glass homes and first-world qualms, exists another Mumbai; one that is littered with tiny houses, arranged in neat boxes tightly placed next to one another, leaving no room for even air to flow through the gullies. Painted in shades of blue from the tarpaulin sheets flimsily resting on the roofs of these homes, this is a city that does not complain, rather struggles, as it works tirelessly to lay the ground for the Mumbai that it cannot inhabit. These streets are sprinkled with middle-aged sari-clad women on the way to take care of other people’s homes, children, dogs, gardens, only hoping that one day, their labour might be acknowledged beyond the meagre salaries they draw. This is the Mumbai of dreamers – people who can afford only to imagine, not experience the ‘dreamy’ life.

Also read: Commuting Via Mumbai Locals

While most citizens living in urban areas contend that these anachronistic beliefs have been erased from the modern social fabric, there is evidence to the contrary. Not only are caste and religion used to sway votes among the working class, but these apparently outdated divisions are unknowingly and sometimes intentionally, still being propagated by the elite in the form of microaggressions. In my opinion, however, the latter can prove to have far more adverse effects on hampering the process of bridging the gap between these two worlds, because unfortunately in Mumbai, those fostering outdated beliefs regarding untouchability and class status, are in positions of power. For instance, many residential complexes in the city have different lifts for members and maids or workers. This begs the question: just because they haven’t used the word ‘segregation,’ is this not an act of discrimination?

What makes the inequality in Mumbai different from other Indian cities is that it manifests so overtly – there seems to be both a lack of physical distance between the rich and the poor and a distinct boundary between the two. This has been craft fully illustrated by Johnny Miller’s Unequal Scenes Project, which captures arial views of urban spaces and cities using a drone.

Through his work in Mumbai, he was able to place the two extremes of Mumbai within the constraints of a single frame. His images are haunting because they call attention to the physical proximity between the two Mumbai’s – these aren’t distant worlds existing at two ends of the city. Instead, they are two completely different living and breathing societies, lying merely a few meters from each other. The only difference is that the tall buildings pierce through the clouds, making them visible, while the slums and huts are concealed, below the allure of this cosmopolitan dazzle. The city is so concentrated with concrete buildings and swanky infrastructure that you cannot help but notice that these cramped spaces are filled with a painfully obscured rift.

Unequal Scenes by Johnny Miller

One track from Zoya Akhtar’s Gully Boy (2019), titled ‘Doori’, summarises Mumbai’s fractured soul – the social and economic disparity between two individuals is much greater than the physical distance between them. Every day, hundreds of cars drive on the streets of Mumbai, holding in them people who can see the world outside their glass windows but perhaps choose not to. They turn their face the other way when a hungry child knocks, and sigh in disappointment at the sight of a street-bookseller. They use window covers to keep the heat out, turn the AC to full to keep the unpleasant smells away and play the radio to drown out the sound of street processions. They use every luxury at their disposal to keep themselves from seeing another Mumbai. But as beautifully depicted by Bong Joon Ho in Parasite (2019), these worlds inevitably clash.

Also read: Home, or the Idea of It

Although Mumbai’s harrowing class conflict should be acknowledged and addressed, it is interesting to examine the city’s charm, despite this conspicuous phenomenon.

On my last day in Mumbai, I drove to Marine Drive. When I sat down on the parapet, I noticed the cacophony of crows fighting over the piece of bread someone thought belonged on the road, and the chatter of the tea-sellers, arguing over whose spot it was. I watched as a group of aunties from a building nearby gossiping about that one odd neighbour whilst completing their evening walk, and I looked at the dreary faces of young officegoers who were just seeking some respite before they returned to their exhausting routines. A couple sitting next to me went 30 minutes without speaking — they nervously held hands as their feet gently brushed against each other; they didn’t want to waste these fleeting minutes on words but on the seemingly timid gestures that they called intimacy.

On my left, two frustrated policemen were ranting about their day’s work whilst feeding a stray dog, and on my right, teenage girls posed for Instagram-worthy pictures against the backdrop of the Queen’s necklace. In a city persistently divided and conflicted, perhaps the sea was its only constant and equaliser. I thought to myself, maybe this was my city’s parting gift to me — a transient moment when I could be alone and together with strangers from everywhere and nowhere, from my Mumbai and theirs as we watched the sun sink into the sea.

Nandini Gumaste is a recent Liberal Arts Graduate from King’s College London and an aspiring storyteller.

The featured image is an illustration by Pariplab Chakraborty. To view more such illustrations, click here.