There are about 360 villages in the city of Delhi. A field trip in the middle of winter to five of these urban villages provided an opportunity to know the life of the people living there.

Traditionally in villages, most of the work is agriculture-based, creating a sense of community and binding the people into an interdependent system. However, when a village is declared as an urban village, the composition of the village changes very quickly. Land and its ownership rights change. Context changes, culture changes and cultural capital changes, too. It is interesting to see the contrast of the urban village – which is “developing” on the one hand and has a completely different way of life, away from metropolitan amenities and lifestyle, on the other.

It becomes pertinent to question the identity of urban villages now. What parts of urban life and rural life co-exist in this hybridised situation of existing? Is it the comfort of accessibility through roads, education, the opportunity for upward social mobility, health care and transportation that urban life has, or the struggles of population increase and pollution? From the rural life, is it the interconnectedness of ‘Jal, jungle, jan and jameen’ or is it the struggles of unchallenged oppressive social structures involving caste, class and gender?

The identity of an urban village seems analogous with the paradox of a privileged woman. Where privilege and oppression co-exist, apparently by covert and overt interventions of the government. Women’s lives, narratives and hushed silences in these urban villages become markers of development for the ones who wishes to see clearly. In all the villages that we visited, women were in the kitchen more than any male member of the family.

Both the women and men said that before the urbanisation streak started in these areas, women were heavily engaged in agriculture and animal keeping work, and to some extent a few can still be find engaged in these as household chores. As for the men, this shift brought new kinds of work, with agriculture taking a back seat. Mostly now, the land is used to generate money – the tenant culture is growing, as was apparent in Ber Sarai, Naraina and Kakrola villages. With this comes an influx of people who were not there before. Spacing and housing challenges are increasing in these ‘Lal Dora’ lands knows as the urban villages of Delhi. And so is the plight of landless people who use to relate to the farmland in various direct and indirect ways.

A furry friend will welcome you with a wagging tail and kind eyes when entering the Rakesh ‘Akhara’ in Nangal Thakran village. The place has hostel facilities, functional lavatories, and a food mess for boys. There is also a sand pit, indoor wrestling ring and a well-equipped gym. For girls, the hostel facilities are not in place. However, girls in and around the village have been coming to the site for training and practice.

A young girl and her father accompanied us to the Akhara. The 12 year old said that she used to go to this site for ‘kushti‘ (wrestling) practices but discontinued it as there is a lot of school and tuition work and no time. Her father added to this – Also, one needs to eat dirt in the process! Indeed, it seems like girls are eating dirt in the process more than the boys. Equal opportunity to both the sexes to train holistically will celebrate the culture of ‘kushti’ more inclusively. Since girls need to be dropped and picked up from the Akhara, the place is less accessible for girls. Now, girls have less time to train, less time to use the gym equipment and hence, less competence. The culture of village wrestling has changed over the years for sure, with the entry of girls in the ring being a step towards inclusion, but we must walk further after the first step.

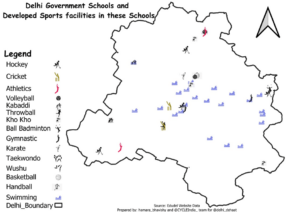

This GIS based map shows how out of 1040 schools under the Delhi government, only 49 have some sort of sports facilities. Wrestling is absent from schools. Delhi has merely 3 stadiums with facilities for wrestling.

Availability and accessibility of education for all accompanied with appropriate sports facilities is something the government needs to be held accountable for. Accessibility of schools in terms of proximity to the village is still a concern for the people. In some villages, there are government schools – MCD and Delhi government schools for boys and girls – while in others, finding education is still a struggle. This struggle is faced by girls more than boys. There is a need for girls and co-ed schools in all villages, so that children do not need to travel for hours to study.

In terms of culture and cultural capital, the people, environment and social institutions play a central role in cultivating it. When the socio-cultural context shifts and changes, then there is a need to facilitate cushioning from an anticipated shock of feeling alienated in one’s own land.

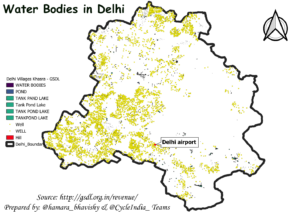

While the water bodies were learning spots for children in the olden days, now there is a textbook culture. So, when a centralised curriculum is followed for the children in urban villages, they face a similar dilemma of that of the remote village children – of not having a culturally and contextually responsive curriculum and hence the dilemma of home knowledge and school knowledge being incongruent and at times conflicting. The NEP 2021 talks about contextualising the curriculum but the implementation for that still needs assertive and didactic interventions.

Near the gram sabha land, you will find a well maintained ‘Johad’ (village pond), with water that sparkles in the mid-day sun, with green bhang weeds and wild berry bushes on the side. The water body is looked after by the Delhi government and is a serene, playful site. Apart from that, a local pond was grey with cement and looks dead. An elderly local woman said, It used to be filled with water, all day long we would just be in the water and play, no need for phones, no need for anything. Now, the pond is cemented. Now, it’s not the same.

Overall, a visit to urban villages in Delhi shows how people’s struggles and lifestyles have changed over time. There is a need to listen to the voices coming from urban villages in Delhi so that space is made for what they truly need.

Apoorva Dheekaw is a 2nd year student of MASW Counselling from TISS, Guwahati

Featured image illustration by Pariplab Chakraborty.