Is Hunger a name? If yes, then whose name is this? The name of a person? Class or Society? Or Country?

Author Dhruba Jyoti Borah tries to find the answer. His novella set against the backdrop of Char Chaporis (the river island) has Farman as a protagonist. Farman in the book is not merely a name of a person or rather the name of Hunger. The novel revolves around the theme of how Hunger – the basic, primitive force shapes the ontological as well as metaphysical presence of an individual. The book pushes the readers to embark on a journey of how hunger kills the innocence of Farman. Farman knows hunger with all the layers.

“First, there would be a burning sensation in his stomach — a desperate cry from his empty belly. Then there would be nothing. This would be followed by a sense of unease, as the indefinable pang relentlessly gnaws at the pit of his stomach and the region just below his chest. Eventually, the pain would subside to a dull ache — curiously numb, apart from a sharp twinge now and then.

As the evening falls, the day’s hunger would result in a stupor. It would overpower him mercilessly, mind and body. Yes, Farman knows hunger well.” (P -17)

Like the slushy quicksand of the chars(the bank of the river), Farman gets caught in hunger, the more he tries to get out, the more he gets inside. No escape route. But the desperate human instinct to try to survive on the brink of loss pushes him to be a failing – a cow smuggler who sometimes even steals cows to smuggle those catches to the nearby country Bangladesh. The novella keeps the readers glued to its pages with the steady flow of events. The structure of the novel is like the mighty river Brahmaputra on whose bank the people of Char Chaporis live. When the readers think that it’s a moment of peace – a respite for the protagonist Farman, the novella breaks the lull and jolts the readers like the river in the rainy season does, it opens the floodgates of misery.

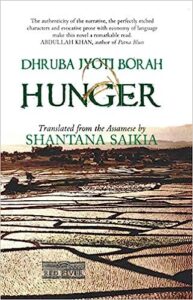

‘Hunger’ by Dhruba JyotiBorah

Translated from the Assamese by SHANTANA SAIKIA.

First published by RED RIVER in March 2020.

The revised version has been published by Red River Story, an imprint of Red River in 2023.

Set in a very remote place, in a small district of Barpeta of the northeastern state of Assam, this novel pulls out the painful collages of miseries of the people who are often absent in the literary imagination of the so-called mainstream literature. Farman belongs to Chars, the riverine islands. Like the Chars, his identity is also fluid. For the people living on the Chars, displacement and losing the last straw are yearly affairs:

“Farman’s family used to live in a low-thatched two-room shack made of bamboo and straw. Every year the floods would destroy the house and they would rebuild it. It was a yearly affair at the char. However, not all lands were inundated. Only the low-lying areas. The higher grounds did not suffer serious damage except when the waters in the Chaulkhowa River rose high.”

Poverty with a conscience is a difficult combination. His conscience and sense of honesty wrestle with his decision to go with Mansoor, the smuggler. Though he agrees to go with him, the readers feel the presence of his gnawing conscience. Farman had no choice but to choose the path of no return. Author Dhruba Jyothi Barua numbs every reader when Farman asks Mansoor Falengi,

“Haven’t eaten for two days. How can I go?”(P- 27)

Isn’t it a question for every poor person in this country?

Farman becomes a falling, not out of greed but out of his basic need. The all-powerful hunger defeats him. Out of his sense of morality, he feels guilty:

“As the sky became call-powerful law seven cows, two pairs of them were bullocks! Hai Allah! There was no boat this time. They would have to swim across the Brahmaputra with the cattle. Farman desperately held onto the tail of a big bullock. Irshaad and the other falling chased the rest of the herd across the river. Farman had no idea how long it took him to cross the river or for that matter how he even manafallingdo it. Three cows and four bullocks! A catch of no less than five to seven thousand at least! What had he done? How could he commit such a gunyah Hai Allah! As the enormity of his sin struck him, he was almost paralyzed with shock. “(P -33)

With the money he earns from the smuggling, he repairs his house and begins a new life with Hamida, his wife.

“With Hamida, his dark and lonely two-room hut lights up.”

The readers too begin to settle and hope for the emancipation of the protagonist, Farman. But like the Greek tragedies, Fate plays the spoil. But in this novel, it’s not fate but Hunger again plays with the dream of Farman. His savings begin to drain and the shadow of hunger begins to loom large, and this time it’s on two stomachs:

“Moreover, there is also the question of his self-respect. He cannot let Hamida go hungry! The monsoon arrives. The river swells. It is not easy to get a job at this time of the year.”(P-42)

Farman searches hard and takes every odd job. But hunger doesn’t even leave his only shelter, Hamida with him. Poor Hamida chooses a better life with Mansoor.

Crime as the author says is like mire. Eventually, Farman becomes a middleman and lastly becomes a thief. Like the layers of hunger, the cyclic transformation of Farman completes from a falling to a thief. At the end of the novel, a boy asks Farman,

“Why do you steal?”

and debilitated Farman’s answer shakes the conscience of the readers.

“The question fills him with an unexplained, indescribable sensation. Something debilitated pulsating, throbbing inside his head, seems to snap. He begins to shake uncontrollably. His eyes bulged. He glares at the boy and stands up abruptly. Instinctively, the boy falls back a few steps. Farman’s lungi comes off as he rises. Grabbing at the falling lungi, without any warning, he begins to wave it over his head. Like a warning. Like a flag. Stark naked and waving his lungi frantically over his head with both his hands, Farman begins to shout, ‘Hunger. Hunger. Hunger’.”(P-61)

The novella should be read not only to understand the poverty that was the constant companion of the people of Char Chaporis but to understand the people of the Char Chaporis of the present time. Much water has been flown on the river Brahmaputra since the novel was first written three decades ago in Assamese, and the condition of the people of Char Chaporis has hardly improved. Still, we have people like Farman who get into cow smuggling to face bullets. Cow smuggling is still a reality in Indo-Bangladesh border areas, where the novel has set in. Hunger is a reality that we often invisibilize. Every year young boys die while smuggling cattle and beef.

It’s said a great piece of literature defeats time. Author Dhruba Jyoti Borah not only defeats time but his novella, Hunger becomes a witness of ever-present Hunger that still plays a vital role in the lives of the Miyan people living in Char Chaporis of Assam.

Moumita Alam is a poet from West Bengal. Her poetry collection, The Musings of the Dark was published in 2020. The book has about a hundred poems written in protest against the humanitarian crisis from the abrogation of article 370, the Delhi riots, and the Shaheen Bagh movement to the unbearable sufferings of the migrant labourers due to the unplanned COVID – induced lockdown.

Featured image illustration by Pariplab Chakraborty.