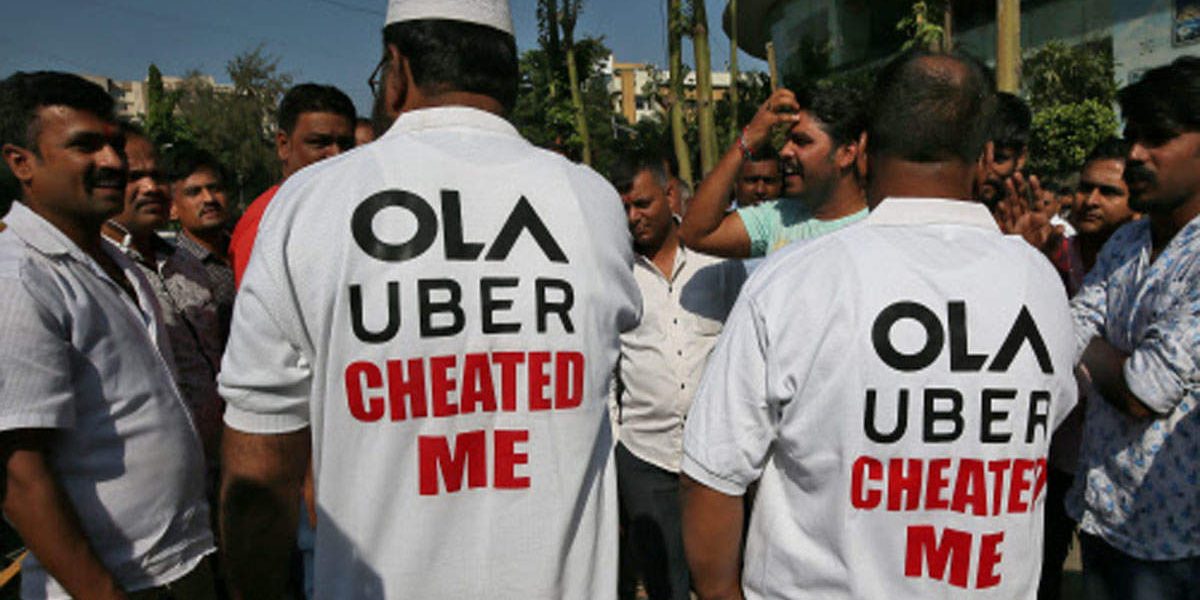

On January 31, as the country grappled with a leaked report showing record unemployment in India, NITI Aayog’s CEO, Amitabh Kant, called a press conference to refute the numbers the media was reporting. One of his main points was that companies like Ola and Uber have created over two million jobs in India.

The kinds of jobs he was referring to are emblematic of the gig economy – workers are hired on short contracts and receive little to no benefits from the company they work for (or with).

Over 46% of India’s formal sector is employed on a contractual basis. We spoke to some blue collar contractual workers in Delhi to see what it really means to be employed in the gig economy.

How far is this picture a true representation of workers’ realities?

Talking to one such driver, unfortunately, paints a rather bleak picture. “We have to put in 12-15 hours of work to make ends meet after spending on petrol and cutting off the commission we owe to the company. I know some drivers who have migrated to Delhi and do not have a home to go to. They sleep in their cars to save on money,” said Arya, a 26-year-old driver from Haryana.

Asif (name changed), a 25-year-old Uber driver, also from Haryana, said, “We used to get incentives on completion of 12 trips in a day. But the company has stopped all such incentives in the last few years. Uber and Ola riders have been protesting almost every year. All our demands fall on deaf ears. Every time we call for a strike, there is a surge in pricing as the number of cars goes down. Lured by the prospect of earning more, some drivers always end up driving despite the strike. This gives the companies reason to not take the protests seriously. They know the desperation of drivers. Some of them will always ride and you can’t blame them considering the kind of backgrounds that most drivers come from. Increasing fuel prices and the slash on incentives means that we now have to ride for more hours to make some money.”

The gig economy – which employs drivers, delivery and other blue collar workers – has boomed over the last few years, but its growth hasn’t improved people’s lives. In fact, without any social or economic buffers, blue collar workers, across sectors, are bearing the brunt of our new labour systems.

Gautam, a 28-year-old, who works as a fashion assistant at a Big Bazaar in Delhi, is one such worker. “I am paid 14,000 per month and an incentive above that if sales targets are met. Ours is a standing job and there’s always a possibility of developing spinal issues later in life. We are given a 15 minute break to sit and relax apart from the 1 hour lunch break in our 9 hour shift,” he says.

Asked about health insurance, Gautam replies, “We don’t get any health insurance. The worst days are during festivals. Most of our sales happen during festive seasons. Our shifts are stretched to 12 hours at a time. There’s no overtime pay and our break time actually goes down. Standing for half a day is too strenuous.”

The Factories Act 1948 limits working hours for an adult to a maximum of 48 hours a week. The Minimum Wages Act 1948, limits the working time for an adult to a maximum of nine hours in a 12-hour shift. Section 33 of the Act further states that the employer must pay double the rates for an hour or part of an hour of actual work in excess of nine hours or for more than 48 hours in any week.

“In apparel or retail outlets in the high rise malls of Tier-1 and Tier-2 cities, those standing for hours to help customers make their choices are referred to as ‘fashion consultants’ or ‘floor executives’. By using such terms, these companies avoid associating them with other workers, which eventually helps in stopping them from unionising,” says Basudeb Burman, a PhD scholar at Tata Institute of Social Sciences who works on labour issues.

While several Indian laws spell out what companies owe to their full-time employees, they don’t necessarily cover the rights of people who work in non-traditional employment situations – loopholes that companies then exploit by using terms like ‘consultants’. And this isn’t limited to just one sector.

Changes in management techniques, increased automation and subcontracting all allows companies to avoid certain labour laws and regulations.

“For example under Companies Act 2013, any company which employs 20 or more workers is bound to provide various basic rights and facilities. By forming subsidiary companies which will have 19 workers, the parent company gives the contract to its subsidiary and avoids the responsibility towards its employee,” says Burman. This often leads companies to hire people on short-term contracts, since employers can then avoid investing in a labourer but still profit from the labour.

These factors have given rise to a category of jobs known as ‘precarious work’. The term refers to a wide variety of jobs – mostly created post the 1991 liberalisation – that are not covered under any of the labour laws.

Precarious work has led to broadly two major issues. First, the informal-isation of the formal sector. Subcontracting may help companies reduce costs, but leave the labourer in flexible but risky economic circumstance.

Employees in these situations don’t have certain rights such as medical leave, the right to unionise and a safe working environment.

Mohammad, a team leader and de facto supervisor of fashion assistants at a retail store said, “We do not get overtime pay. But the newer employees have it worse. Most of the recent employments are contractual. This was never the case before. So most of the young Fashion Assistants here are not eligible to the incentives, like gratuity, that we (older, full time workers) are. ”

Why are companies resorting to contractual employment?

“It’s easier to kick them out. If you find a contractual employee problematic, you don’t have to risk fighting a case in court. Plus, it saves them much more money,” explained Mohammad in a matter-of-fact tone.

“The workers in the gig economy are subservient to the whims of the market. Their condition is entirely dependent on demand and supply. There has been a deterioration in labor rights and a serious deficiency of trade union rights. These sectors do provide jobs but the quality of the jobs does not validate the claims of the sector being a good employment creator. There is no employment security, social security as the organised sector is moving towards informalisation,” says Dr Mukhul Sharma, former editor of Labour File.

However, just because employers have reduced their obligations to employees doesn’t mean they lower their expectations from these workers.

Rahul, a 23-year-old shop assistant who mans a store alone in Select Citywalk, described his work environment: “There’s a camera right above my head. My boss is always watching over me. If I sit on my stool for too long, he immediately calls me on my phone and instructs me to stand. The worst part is that we are never given leaves apart from the one holiday per week. Any additional holiday, whatever the reason for absenteeism may be, results in a deduction of payment.”

Nearly half our of workforce is exposed to such precariousness.

Why do workers continue to stay on?

“My family migrated from Nepal 20 years ago. We still live in a rented apartment. I am the eldest son and the financial burden of the family is riding on my shoulders. I will also have to finance my sister’s wedding. I wish to one day get to the managerial position of the store,” said Rahul.

“I don’t like my job at all. I joined the retail sector because I had no other choice,” Gautam said, but then, when asked about future plans, he says, “I have no choice. My entire experience is in retail. I hope to be promoted to a managerial position some day.”

The digital giants have created convenience for consumers – and new lows for labour

Away from the world of brick-and-mortar retail, companies like Amazon, Zomato and Swiggy have redefined the concept of a job.

Delivery jobs pre-date app-based delivery businesses, but now, as Burman explained, “These companies are employing workers but they are not directly under them and they are not getting any traditional social security benefits under these companies.”

According to these companies, they don’t own any assets. For example, Ola doesn’t employ its drivers or own the cabs. Amazon doesn’t own the products it sells on its website. Swiggy doesn’t own the restaurants or employ the people who deliver food.

At first, workers are drawn to these companies because of the flexibility and incentivised pay structure. Deepak, a first-generation migrant from Uttar Pradesh and a delivery partner for Uber Eats, earns Rs 40 per delivery. On average, he makes approximately Rs10,000 per month if he works for exactly eight hours a day, but being the only earner in his family, he regularly pulls 12-hour days, earning closer to Rs 15,000 each month.

Uber Eats pays him an incentive of Rs 250 if he makes 15 deliveries in a day day, but it doesn’t pay for petrol or offer any social security benefits to delivery partners. There are no paid leaves in case someone falls ill and needs time off.

Such treatment may have been legal until now but countries are already taking steps to rectify the situation.

In the UK, the government has proposed a Good Work Plan, under which gig employees will have the option of getting a stable contract and various other benefits after six months of work. The EU has also drafted a bill for transparent and predictable working conditions.

Discussing the Indian context, Sharma said, “Workers and their lives should not be left to the mercy of the employer who can mostly get away without providing any security to their labor force. It’s a weak argument that labor laws are hard to enforce. Employment should not be at the cost of a worker’s dignity, health, and livelihood.”

The Indian government hasn’t yet tabled any draft bills on this, but late last year, NITI Aayog released a strategy paper that calls for greater compliance with existing laws and the codification of labour laws. The paper proposes reforms aimed at achieving the “optimum combination of flexibility and security” – increased flexibility for the employer without compromising on the security of the worker. How this is actually implemented remains to be seen.

As policymakers around the world continue to puzzle over the impending crisis of automation, human unemployment and the still-growing gig economy, blue collar workers have no choice but to stick with such precarious work.

Shreegireesh Jalihal, Arindam Roy and Tapasya are pursuing a postgraduate diploma in english journalism at Indian Institute of Mass Communication, New Delhi

Featured image credit: Reuters