This month, our national media houses have taken to predicting election results on CGI helicopters above a CGI map of India.

But wait – first, let’s talk about Omelas. Written in 1973, The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas is is a short work of fiction by Ursula Le Guin.

In the city of Omelas, everything is beautiful. There is no guilt – although there is sex and beer if you want it. In fact, the reader fills in the specifics of the utopia they’d prefer. In Omelas, you are finally happy. No disease, no poverty, no Our Planet reminding you about dying polar bears and your role in the climate crisis.

In Omelas, there is a cellar. Inside that cellar is a child upon whom all this happiness rests.

The people of Omelas are wise because they collectively accept a difficult truth – a social contract: that for the happiness of Omelas, one creature must suffer alone, in the most degraded conditions. Always. The suffering isn’t a byproduct – it’s the point.

It would be stupid to say we live in Omelas.

§

Variations on a theme by Ursula Le Guin: I

Say, like me, you live in Delhi. Say, like me, you grew up with a certain amount of power. Maybe the ads were talking to you.

Delhi is nothing like Omelas.

Here, even if you live in a gated apartment complex and travel in an air-conditioned Uber, the driver asks you in Hindi – a little desperately – for a good rating.

Perhaps you’re driving. You get stuck at the red-light and see a child crisped brown in the sun. He bangs on your clean window with his snot-crusted hands. If you’re in an auto, the child throws a wilting rose at you, falls at your feet violently, palms in prayer. Maybe you shove her away and think of the translucent balloons she is selling – lighting up the evening with twinkling LEDs as she lurches away from your vehicle to the next.

Maybe you even use this imagery of floating lights in an essay or something. An advertisement.

In Delhi, dissent is not appreciated. Our colonial inheritance, Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, punishes ‘sedition’. In letter for ‘incitement to violence’ ; in practice, for protesting government approved activities like the corporate acquisition of Adivasi land or urban bastis for ‘development’.

In Delhi, the police renew Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code every two months, prohibiting assembly of five or more persons – carrying placards, or shouting slogans – outside ‘designated protest sites’. To prevent the “disturbance of public tranquility,” any protest must take place at Jantar Mantar, Ramlila Grounds or Parliament Street.

Jantar Mantar works because no one goes there unless they’re going to protest. The public remains tranquil.

Who even protests?

Only those ‘professional protester’ types. College students, farmers, the poor, the ‘gays’? People without a 9-5 job or a family. Aunties. People with fat wallets.

Meanwhile, the tranquil public is comprised of adarsh family units. The adarsh family unit stays on the peripheries of protests – even when it is comprised of roommates.

The prayer of the adarsh family unit for its members:

“If they’re gay, may they be the kind of gay who can buy what Anouk advertises. If they’re mad, may they be the kind of mad who are only depressed because of something specific and time-limited. If they’re women, may they have the money to not occupy a public bus, and the luck not to have a pushy partner or an over-friendly uncle. May they never travel alone. May the body they are born in be the box they like.

May they be rich and upper-caste enough so that the rules don’t apply. May they be rich enough that they’ll be able to buy effective Vogmasks because the air here is killing us.”

§

Variations on a theme by Ursula Le Guin: II

Walking, shouting, talking and sweating with the many womxn protesting in Delhi over the months leading up to elections means de-familiarisation.

It means forgetting to reduce people into ‘populations’; forgetting that being a womxn is equivalent to being a victim.

The Farmer’s March, November 2018

India’s agrarian crisis amounts to a slow genocide – one which feeds us as it happens.

At the Kisan Mukti March, I meet Pooja Ashok Morey, 21 and in law-school. She has travelled to Jantar Mantar Road with her parents from Beed Zilla in Aurangabad, Maharashtra.

Along with other farmers organising under Swabhimani Shetkari Saghtana (SSS), they have crowdfunded this journey, filling three trains from Kohlapur. Richer farming families who haven’t come have sponsored the Rs 3,300/head train fare for others instead.

Through our conversation, Pooja name-drops Raju Shetti over a dozen times. A member of parliament in the Lok Sabha, he founded the SSS and has a track record of successfully agitating for farmers’ rights in the sugarcane belt of western Maharashtra.

“Raju Shetti is an idol” Pooja says, her eyes lighting up. She is a “krantikari” her father tells me. When she’s done with law-school, she’s set on being a union-leader “just like Raju Shetti”.

About the “Ladies Mantri, Pankaja Tai” she is scathing: “’We are with you’ bolti hain, and then she looks at caste.”

Pooja and her parents are so politically educated, I feel ashamed at how little I know. For an hour they school me on interest rates in China for cash crops (2%), the lie of demonetisation, how the Modi government abolished the Planning Commission in favour of corporates, and the Karza Mukti Bill.

Pooja talks about their demands confidently: “Lagat se 50% adhik paisa kisaano ko milna chahiye (Farmers must get 50% more than the cost price.)”

On learning I’m Bengali, they begin to talk about the traders’ mafia in Kolkata – where they travel to sell fruit (sweet limes mostly). Tomatoes are bought at Re 1 per kilo from farmers, and sold at Rs 20 a kilo.

Sometimes, the fruit is sold and then there is no money to head home. Often there is no rain. The Moreys own five acres of land. “We don’t make even Rs 50,000 a year.”

As we say goodbye, they urge me thrice to vote in the elections.

By the time I leave, it’s dark. The remaining farmers make their way to Ramlila Maidan where they will camp for the night before the long journey home. The roads are strewn with paper which minimum-wage workers sweep up. I wonder about people who are drawn to grassroots activism; and who cannot be apolitical.

I pass a news crew for [redacted big-name centrist TV news channel]. They look about my age, millennials. One of them stands in front of the news van, frantic: “I was supposed to have farmers in the background, but they’ve all left now!”

Another pulls his jacket over his head, entertaining the others sitting on the pavement:

“Hum itna poor hai, loan karke, apni kidney bech ke beti ki shaadi karwa rahe hain.”

(I’m so poor, I’ve taken a loan, sold my kidney to marry off my daughter.)

As I walk away, I hear one of them say, “I’m a spoilt Delhi girl… I can’t help it.”

The Stop Trans Bill Protest, December 2018

The Trans Bill 2018, passed in the Lok Sabha, ignored recommendations of activists and the earlier landmark NALSA judgement which laid down the right to self-identification. Among other things, the Bill mandated a “screening test”, criminalised begging – the primary source of income for the hijra community, and enshrined the natal family as ‘custodian’.

This protest is smaller. It is led by grassroots activists, many of whom have travelled from down South and are helming the fight.

I go alone and bump into acquaintances from the queer community. One, a law student at Delhi University, will later be elected convenor of my university’s queer collective. Even later, her family will demand she cut all ties and present herself as male. They will send her to therapy. She will endure dysphoria so that she can complete her law degree.

I stand beside women in colourful sarees and large earrings from a hijra collective in Tamil Nadu. We smile at each other bereft of a shared spoken language. One of the women beckons me to come closer. She touches my red lip with her finger and raises an eyebrow: “Kya hai?”

“Colorbar” I say and she nods in approval.

On stage, a trans man takes the mike, shouts: “Hum apna adhikaar maangtey – na hum tum se bheek maangte (we demand our rights, we’re not begging!)”

It’s a compelling slogan and we chant in response. Later, a femme will remind us of the exclusion this implies for the hijra community and some of our trans sisters.

The revolution is not televised but the Bill lapses in the Rajya Sabha.

I think about how the family unit socialises us. How five years ago, my internalised transphobia would have me shrinking away in fear.

Look, we have to admit these things. It’s our only hope at not exceptionalising and digging into the roots of the problem instead. I’m sorry – we learned to hate ourselves and those who fell outside the ‘adarsh’.

Across the road at Jantar Mantar, a group of men holding their own protest – in support of the exclusionary rhetoric the BJP has propagated with the National Register of Citizens to push ‘illegal immigrants’ out of Assam.

Women March For Change, April 2019

Before the elections and the first phase of voting, several womxn’s organisations and activists mobilise a massive march across 100 locations in 20 states under a single banner. It is a call to womxn voters to symbolically counter the attack on the idea of an India of pluralities. To protest the shrinking space for dissent and sovereignty of our institutions.

I go with classmates from my Master’s programme in Gender Studies. Our dean has ‘unofficially’ urged us to put our bodies where our theory is. We convince other professors to cut classes short “for democracy!”

In the height of summer – at noon – we are a thick mass of womxn sweating down our necks, marching from Mandi House to Parliament Street.

We are Safdar Hashmi’s words in the flesh: “Auratein uthi nahi toh zulm badhta jaayega!” we chant.

(If women don’t rise up now, atrocities will keep increasing)

We scream: “Azaadi! Bhukhmari se! Azaadi! Manuvaad se! Azaadi! Pitrsatta se! Azaadi Azaadi Azaadi!”

(Freedom! From hunger, from Brahminism! From patriarchy!)

It Impossible to say these words out loud without remembering the sedition case, arrests and media-trials of Kanhaiya Kumar, Shehla Rashid and Umar Khalid for being “anti-national”. It is impossible not to think of Najeeb Ahmed. It is impossible not to think of Rohith Vemula, of Delta, of Kunan Poshpora, of Thangjam Manorama, of the Koregaon 9, of G.N Saibaba – a list without end.

A legacy of oppression; a legacy of resistance.

It’s electrifying to be here. I shout louder.

Once we reach Parliament Street, a journalist, whom India’s brand of misogynist-nationalist would slur a ‘presstitute’, takes the mike. Beside her, a sign language interpreter translates.

At the back is a giant banner made by students from the Performance Studies department in our university. I take over one of the stands for a bit, so someone else can go drink some water.

It reads “SAVE OUR CONSTITUTION”.

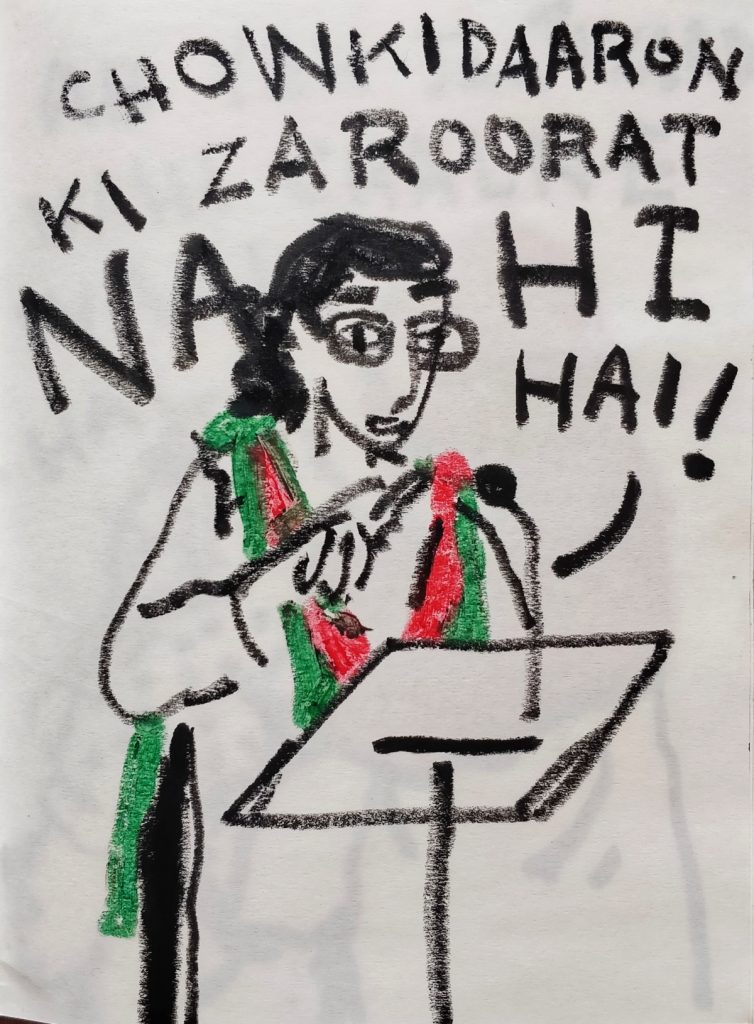

Women’s ‘Apolitical’ Press Conference, May 2019

Once voting begins, Prime Minister Modi – who has famously never given a press conference – gives a televised, publicised ‘apolitical’ interview to pro-BJP Bollywood actor, Akshay Kumar. They chit-chat about the best way to eat mangoes. In response, womxn’s groups organise their own at the Press Club. They raise a list of 56 questions for Modi – a riff on his hyper-masculine bragging about his 56-inch chest.

Question 1. How many jobs were created in the last five years? Why is the government suppressing official data on unemployment? EPFO (Employee Provident Fund) data represents formalisation of economy, not job creation. And most loans under Mudra are too small to create any employment.

Question 5. More than 40 whistleblowers – the real chowkidars – have been killed since 2014 for exposing corruption and wrongdoing. Why has the BJP government not operationalised the Whistleblowers Protection Act passed in 2014?

Someone performs a poem which ends “Jab jal raha hai desh, tab thandi gharon mein baith kar aam khaiye”.

(While the country burns, sit in your cool houses and eat mangoes.)

I sit beside Suman from Kusumpur Pahadi, a basti near the richer locality of Vasant Kunj.

She has been working for seven years with RTI activists, mobilising womxn in the community.

The government provides 5 kg ration per month and in Kusumpur the ration-dukaan, too, is only open five days a month.

“A person can’t survive on that!” she says.

They no longer get subsidised sugar or kerosene for stoves – and the faulty implementation of the Ujjwala scheme has them paying out of their own pockets.

“For 5 kg we have been agitating!” she says. “Look, even if I don’t work with an NGO, it is my adhikaar (right)”.

“Sarkar is running the country. When we run our families we think of everything, but sarkar doesn’t even know how many bastis there are in Delhi!”

Unemployment is so bad, their boys are roaming around. “Sharaab peete hain (they drink alcohol)” she says, gesticulating with her hands.

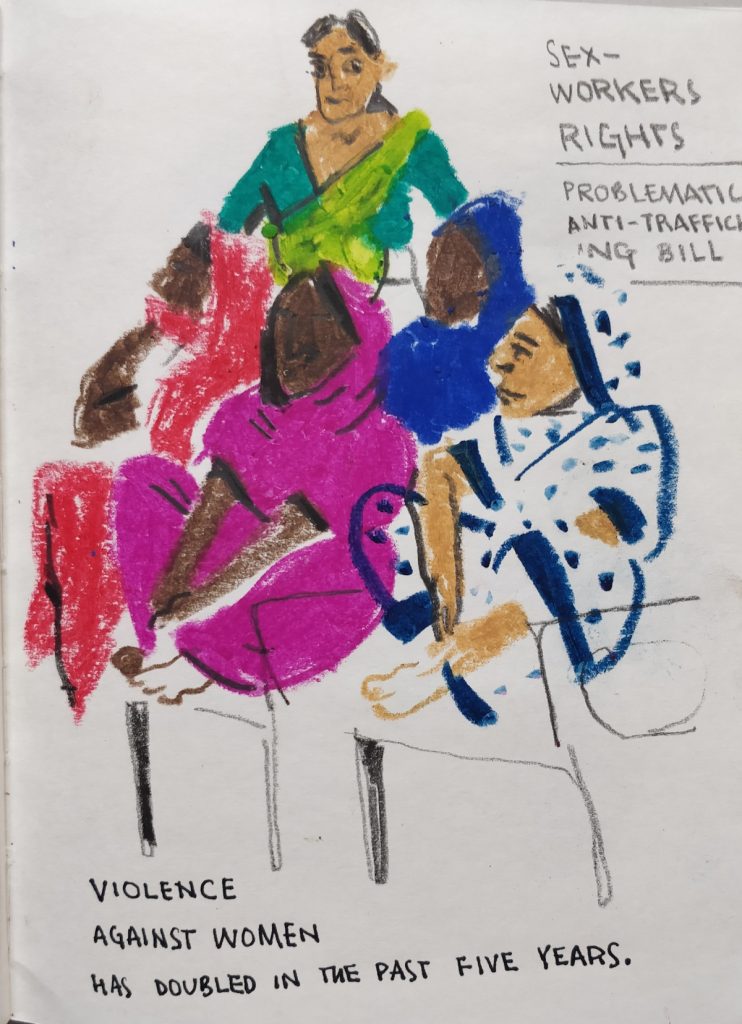

On stage, a womxn speaks about the Anti-Trafficking Bill and how if you don’t have an Aadhaar card, you can’t avail ration or get admission in government schools.

“Humari itni sex-worker behene hain” she says “They don’t have Aadhaar. They can’t get admission for their children. And now the government is taking their rozgaar away?”

Personhood nahi mila toh aam khaiye.

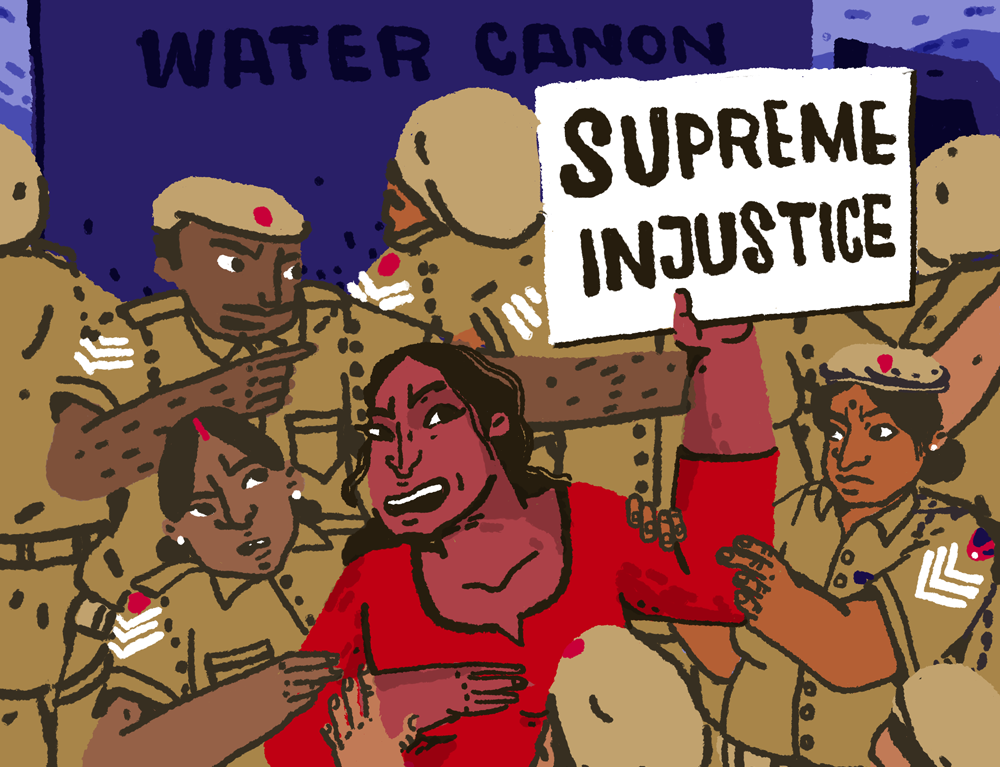

#SupremeInjustice Protests, May 2019

After an ex-Supreme Court staffer alleges sexual harassment and victimisation by the Chief Justice of India, the CJI sits in on his own case, maligns the reputation of the woman through the Bar Council of India, and is given a clean chit. The allegations are declared to be a “conspiracy to undermine the independence of the judiciary”.

Womxn across Indian cities take to the streets. #MeToo.

On day one in Delhi, they protest outside the Supreme Court.

On day two, outside Rajiv Chowk metro station in Connaught Place. I am detained until sundown along with 15 others for violating Section 144 and for not sticking to Designated Protest Site.

By day four, they have taken away and detained 106 womxn and allies within 20 minutes of assembly at Mandi House. Elsewhere, I have written about the non-violent violence of ‘detention’. Here I want to tell you that on day four, along with other womxn activists I visited the Assistant Police Commissioner to ask that the detainees be released. He was polite and firm. He made the call.

In the thick of elections, the police have better things to do than turn up to protests, he told us. “Protest as much as you like at Jantar Mantar. The media will turn up”.

Afterwards, outside, the activists congratulated each other and took a group-picture. “We knew it, actually,” they said.

Where thousands of farmers walk miles on foot to demand attention for their dying crops, their dying families without even a blink from parliament – a Jantar Mantar protest is routine.

At the heart of protest is disruption, is to shake the ‘population’ out of normalcy, to cry out that this – the status quo – cannot be the normal.

So, the drama of over a hundred people turning up, knowing that there is a chance they will be detained – is also sort of the point. It says, this is not okay.

§

Variations on a theme by Ursula Le Guin: III

All dystopias at their heart have already happened to certain kinds of people.

It would be fallacious to call Delhi Omelas. In Delhi, we are slowly dying from toxic air – but we are still walking around, so we don’t say anything.

It would be wrong to call Delhi Omelas. We walk around the manholes, see the manual scavengers emerge from the darkness we sidestep – dread the thought, what if we should stumble?

At the end of the story, Ursula Le Guin writes, there are a few who – having seen the child in the cellar – grow quiet and leave.

“The place they go towards is a place even less imaginable to most of us than the city of happiness. I cannot describe it at all. It is possible that it does not exist. ”

Considering Omelas, physicist and writer Vandana Singh describes her problem with dystopias which are so often premised on “the individual as the Lone Ranger hero.” When actually, the “trouble with complex problems like social inequality and climate change is that they require masses of people to work together”.

I think having described the last few months of protest, what I am trying to say is this:

Let the record show that masses of womxn protested.

They screamed in Omelas for freedom, in different languages. They got sick, they went home and rested, they took turns, they tweeted – making hashtags trend when Big Media was out reporting each time the Prime Minister changed costumes or an actor had a #hottake.

Writing this as the exit polls predict a majority for the Hindu Rashtra-propagating BJP, I feel ill at the prospect of five more years.

I do not want to say that we will survive. Because many have not survived this government. Because demonetisation casually took lives. Because just yesterday, a Dalit man was attacked for daring to have the self-respect to sit on a chair.

What I want to tell you is that the womxn tried.

And whichever government comes into power on Thursday, the womxn will keep screaming.

And you – what will you do?

Riddhi Dastidar is a writer, journalist and Gender Studies scholar at Ambedkar University Delhi. She was a finalist for the 2019 Toto Award for poetry. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Harper Collins Anthology of QueerPoetry South Asia, Glass, Firstpost, Scroll.in, The Wire, Soup Magazine and elsewhere. You can follow her work on Twitter and Instagram: @gaachburi

Kruttika Susarla is an illustrator, comic maker, and graphic designer based out of New Delhi. Her work explores themes of gender, sexuality, and observations on the status quo. Her clients include Google, FRIDA, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Human Rights Watch and Vogue among others. You can follow her work on Twitter @kruttikasusarla and Instagram @kruttika

Featured image and illustrations credit: Kruttika Susarla