The Braille graffiti project at Jadavpur University, Kolkata, came about as part of a class presentation on graffiti and disability by our group, ‘The Graffiti Joint’, for our M.A. final year course at department of English. Our course co-ordinator for the project was Ishan Chakraborty, a person with visual disability.

Inspired by a series of Braille graffiti by an artist called ‘The Blind’ in Europe, our group put up a similar installation at the UG arts building in our university. That’s how we created India’s first Braille graffiti of this kind.

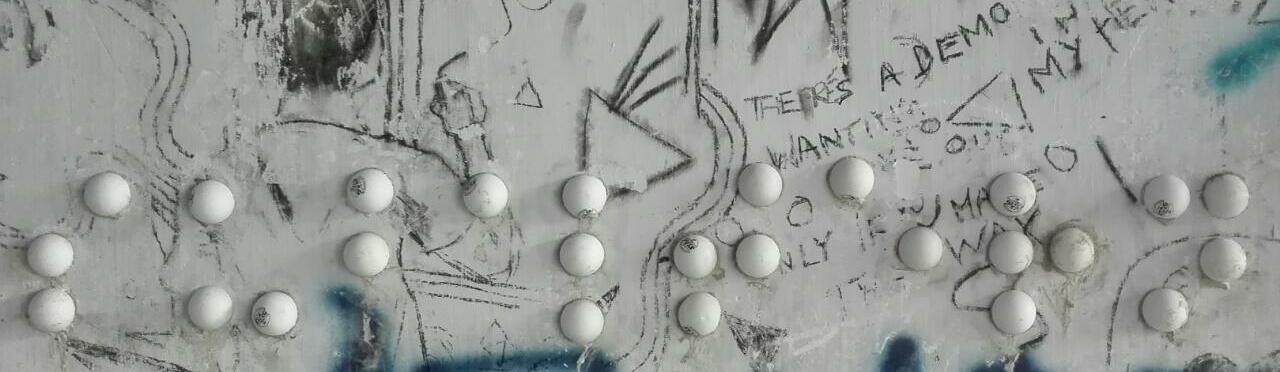

The graffiti reads ‘subaltern’ and we have made it by sticking halves of table tennis balls on the wall with screws and cement. The members of the group – all M.A. final year students at the department of English – are Subhradeep Chatterjee, Utsa Ghosh, Chandrima Mukhopadhyay, Anik Mandal, Manikankana Sengupta, and Emon Bhattacharya.

The process of creation

We started out by using some online Braille translators to write the word ‘subaltern’ in Braille letters, which we traced on a piece of paper using halves of table tennis balls. Then, we cut out the markings in correspondence with the Braille letters to make a stencil, and used it to make dots on the walls resembling the Braille script using crayons.

After preparing the initial canvas, we hammered the screws wrapped with coconut fibre into the crayon markings on the wall to create a firmer grip for the table tennis balls.

Finally, we filled half-cut balls with a cement and sand mixture and stuck those up on the walls and taped it around to leave it to dry overnight. The following day, we removed the tape. Thus, we completed the installation.

The Braille graffiti reads ‘subaltern’. Photo: Shubhradeep Chatterjee

Making art accessible

Graffiti, as an art form, has always gone beyond the boundaries of artistic expression and aesthetics, with its political undertones – aiming to start a dialogue about various issues.

Braille graffiti, such as the one we have put up, is particularly effective as it enables and encourages interaction between the blind and the visually abled.

“In a socio-cultural situation where ‘respect for difference/diversity’ is increasingly becoming a contested idea, dare I say, this is a bold step towards not mere tokenistic integration but inclusion in the truest sense of the term. This, we can say, is one of the may small, albeit significant, steps towards making the department culturally accessible (which is as important as making the space physically accessible) for (visually) disabled persons,” said Chakraborty, our co-ordinator.

Also read: My Experience With Travelling in Indian Railway’s ‘Divyang’ Coach

He further added that the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act 2016 is about ensuring accessibility of art and culture for both recreational as well as educational and professional purposes. “But ensuring accessibility usually remains confined to removal of structural barriers which are more often than not merely tokenistic in nature. These lack the true spirit of inclusion which calls for innovative ways of ensuring a holistic and humane approach for the same,” he said.

His essay ‘To the ‘Other Senses’: A Dialogue between Visual Arts and Visual Disability’– published by International Research Journal Persons with Special Needs and Rehabilitation Management, Centre for Disability Studies – focuses exactly on this issue. He talks about the importance of accommodating persons with disability in the field of art and culture and how that remains more or less unexplored in India.

Professor Ishan Chakraborty with the Braille graffiti. Photo: Subhradeep Chatterjee

Subhradeep Chatterjee, one of the students involved with the project, had previously observed in his research paper tilted ‘Art and Disability: Introjections and Underlying Politics in Subcultures and Genres’ – published in the same journal – that Braille graffiti relies heavily on the politics of subversion. He notes that it “inverts the ‘normal’ scenario where it is the visually disabled who don’t get access to the graffiti.”

This graffiti, he adds, “promotes communication between the visually abled and the visually disabled as the latter are usually informed about the said graffitis, and then they read and decipher its meaning”. This paper was behind our collaborative project, whose principal motive was cultural accessibility.

While working on the topic of Disability and Graffiti, we thought about taking this discourse outside our classroom, and hence we put up the installation. Sure, it’s important to make public spaces physically accessible to the disabled. But, it is equally pertinent to understand that access to art is not a luxury and should not be treated as such.

Also read: Here’s What Working With an Invisible Disability is Actually Like

It is arguably tricky to put these installations on the streets and anywhere outside the university – as it is done in the Western countries.

In comparison to the West, Braille literacy is much lower among the visually disabled in India due to the non-availability of such modes of education. A large number of blind people do not know how to read Braille, thereby making it futile to install these in public places. But, such projects can possibly attain more meaning and utility within a university, where a large number of blind students know how to read Braille.

The way forward

We have put another graffiti – which reads ‘look’ – in our university with the approval of the head of department of English.

‘The Graffiti Joint’ aims at making art a part of the daily lives of the visually disabled students in the university. We hope that more attempts are made to ensure cultural accessibility and inclusion in the truest sense of the term within the campus space and beyond.

Manikankana Sengupta is pursuing masters in English at Jadavpur University, Kolkata. She is always curious about new words and the worlds they open up.

Featured image by special arrangement