Ninety-eight days.

It had been 98 days since the lockdown, and it was the first time in a long time that I was stepping out. A huge part of me longed to be ‘outside’. Outside where big things happen, outside where the flower blooms on the crack of the footpath, and outside where people have fun – or well – so I hear!

I finally settled on going to a nearby park in my area. I was so excited by the prospect of finally stepping out. I vividly remember being overwhelmed with the technicolour flowers, the incessant birds chirping and seeing people – surprisingly so many people. I remember hearing a group of uncles discuss the new WhatsApp forward of how morning walks give immunity against COVID-19. I remember smiling to myself. I was absorbed in soaking in what was familiar earlier but felt so eerily unfamiliar now.

However, I forgot one thing. I forgot what it means for a gendered body to occupy space. And it wasn’t long before I got reminded of it.

I saw the same group of uncles, who were discussing their WhatsApp forwards earlier, stare at me now, ogling, but mostly studying and reprimanding me with their gaze.

I was confused and unsure of what to make out of it. Did they see me notice them? Do they know me? Was I missing something? I walked ahead, unsure of what made me so conspicuous. It was then that I saw Seema and Poonam aunty, who I was familiar with, in their regular suits and sports shoes. I nodded a namaste at them.

“Aree, you’re back from your college?” Poonam aunty asked with enthusiasm.

“Yes, aunty!” I replied.

“Kaafi modern ho gayi! Wearing such shorts and all, haan!” Seema aunty remarked with a wry smile.

It hit me then. I was wearing the shorts that I usually wear on my distant university campus, but I was now in a middle-class locality park in Delhi. I immediately realised my ‘mistake’ and tried to make myself as small as possible before I could reach home.

That day, I reminded myself of the script that I usually used to rehearse before stepping out of my house. Be small, be inconspicuous, or better, don’t be outside if you don’t have to be!

But the recent case of moral policing of Samyuktha Hegde and her friends by Kavitha Reddy and others in Bangalore compelled me to revisit my own position. Hegde was allegedly harassed for wearing a sports bra while she practised hula-hooping. In the video shared by Hegde, Reddy says, “These girls are too smart” – a phrase which sounds like a compliment but is often employed as an insult.

Though unfortunate, this incident wasn’t surprising at all for someone who grew up being familiar with the culture of moral policing.

Also read: Schools Need to Stop Shaming Girls for the Length of Their Skirts

Starting from school, teachers measure the length of the suit and skirt. I remember my principal asking “who was I trying to impress” when I wore lip balm for my chapped lips. The culture that exists at school is sometimes unwittingly accepted. Some of the boys from my school now continue to moral police their partners. Some girls grew up and continue to make themselves as small as possible. The same case of moral policing happens at homes, parties, at lounges, at colleges, politics, protests and at any and every place that can be spatially marked. Families, education institutions, friends, religion and communities are all at fault to some extent or the other.

Sometimes I wonder: Is there really no solution at all other than invisibilising ourselves and falling in line to avoid policing? Is the only plausible solution that exists is to be smaller?

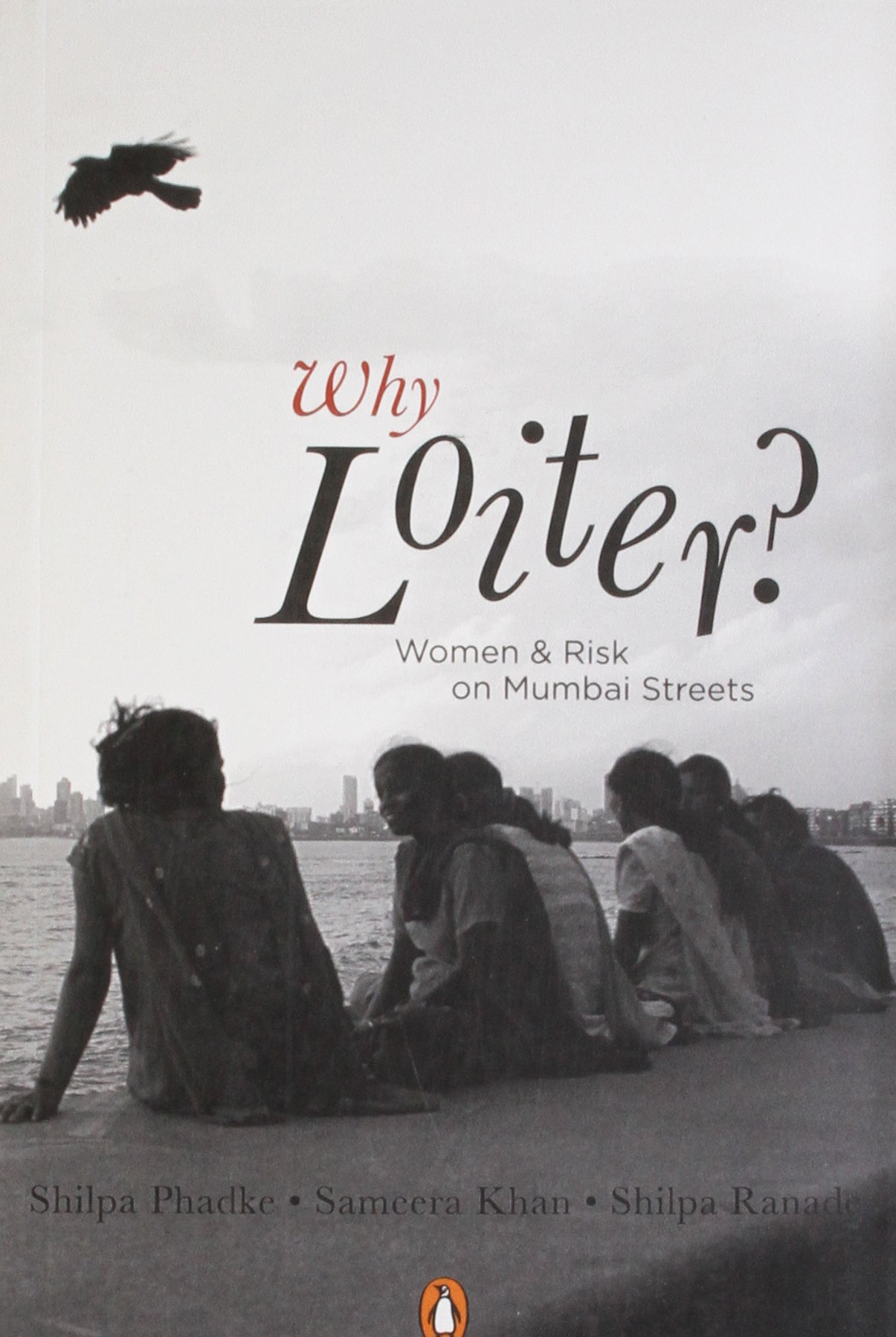

Why Loiter

Shilpa Phadke

Penguin, 2011

Reading Shilpa Phadke’s Why Loiter, I realised it’s quite the contrary. In her profound work, she asks simple questions such as who’s having fun? Can girls really have fun? Is fun conditional?

Through a trenchant analysis, she points out that having fun in a public space always comes with “terms and conditions” attached for girls and women – the particulars of which depends upon one’s location: caste, class, religion and influence in a given society.

Through a careful detailing of the history of space and its relationship, Phadke shows that whenever women are out, they “need to demonstrate a purpose” to be out, unlike men who can be out for fun. I remember a friend asking me once: how many times can you see a group of young women chilling at a local park together? Not doing anything but just chilling? I couldn’t answer that question.

Phadke then, in a section on “imagined utopias”, proposes a simple yet groundbreaking idea that women should loiter.

Loitering is still seen as an unfeminine act, and the simple act of occupying spaces has the potential then to “subvert the performance of gender roles”. This simple act of occupying public spaces also has the potential of questioning the binary between domestic and public space that has long been used to keep women in place.

The logic dictates that as more women step out, the relationship with space would be renegotiated and it would be kinder as well as safer. She urges women then to take risks and occupy spaces but most importantly, to have fun. In doing so, she suggests that violence and quest for pleasure aren’t separate things but rather part of the same ongoing demand for equality.

I am not certain though that loitering alone can amend this fissured relationship of gender and space. However, if loitering and occupying space in a post-Covid world is what it takes for an undifferentiated right to public space, then so be it.

Ridhima Manocha is a final year Media Studies student at Ashoka University and has authored the book, The Sun and Shadow.

Featured image credit: Samyuktha Hegde/Instagram