In 2014, when Kashmir was trying to come to terms with the unprecedented floods which devoured much of Srinagar and many other small and big towns, I was sent to Delhi. Repeated shutdowns and curfews had severely affected my studies – owing to two summers of conflict in 2008 and 2010 – and my parents decided that I be sent to the national capital to be able to continue my schooling at Jamia Millia Islamia and eventually at Delhi University.

Back then, many of my friends and seniors in Kashmir had to suffer the consequences of living in a conflict zone. Some ended up in police lockups, while others had cases registered against them. My parents wanted me to move out of Kashmir both for a better education and to protect me.

During the past six years that I have spent here, I had started to feel privileged since I had managed to stay away from conflict. I had defeated the cost this conflict could/would have incurred on my education. Stereotyping and the casual name-calling, from friends and adversaries alike, did bother me at times, but people back home were suffering more.

Over the years, my level of equanimity increased, probably because my education was going well. I was studying the course of my choice, and it was more than I could ask for.

On August 5, 2019, Article 370 was scrapped, and a subsequent ‘security’ lockdown brought everything in Kashmir to a standstill. Most of my friends and acquaintances here in Delhi remember those days like any other news cycle; those events were similar to demonetisation and surgical strikes. There were a few days of protests at Jantar Mantar and Twitter hashtags, both in favour and against the removal of the special status.

For me, it was more than that. My family went incommunicado for a month, and that was a lot for me to bear. The communication lockdown did ease – although partially – but not before traumatising out-of-state Kashmiris like me.

The conflict had finally caught up to me and the worst was yet to happen.

Also read: In India’s Borderlands, Education Needs to Start at Home

My father, who owns a retail furnishing shop in the southern Kashmiri town of Anantnag, went out of business. Our shop, the sole source of income for my family, remained closed for eight months after August 5. The rented space cost my family a fortune, and the coronavirus lockdown has only made the situation worse.

Meanwhile, I was preparing to apply for my masters since it was my final semester. I had applied to Ashoka University, touted to be India’s leading liberal arts university. I wrote essays and qualified round after round – including a comprehensive application process, a telephonic interview, and an hour-long personal interview – until I got my acceptance letter on April 20.

The programme I had applied for was expensive, but I was told that the university was generous in providing financial aid. I applied for financial assistance and supported my ask with bank statements and income tax returns of my father’s shop explaining the financial condition of my family with regard to the August 5 lockdown.

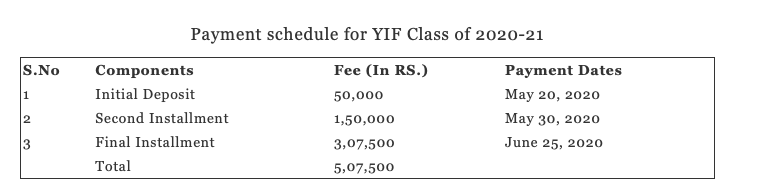

Unfortunately, it did not help me. I was still required to pay Rs 5,07,500 for the one year course. Worse, I had to make the payment in three not-so-easy instalments and within two months.

I know that some of my not-to-be Young India Fellowship programme batchmates, whose financial aid applications were evaluated according to their needs, were lucky enough to be able to secure an admission.

But talking about my application and the reason I had to let go of this opportunity, I believe that universities (both privately owned and publicly owned) do not have any mechanisms in place to deal with students from conflict zones. There were instances when Kashmiri students were heavily fined for not being able to pay their fees on time because of the communication blockade. Many had to return home due to the shortage of resources, and also because of safety concerns.

Also read: Amidst Lockdown, Kashmir’s Online Classes Are a Disaster Waiting to Unfold

The difficulties students like me face are very different from the mainstream. It is, therefore, not fair to use the same models and systems to evaluate us when it comes to fee concessions and financial aid granted by various universities.

According to a statement put out by Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KCCI) in October last year, local businesses and trade in Kashmir faced losses of Rs 1,705 crore due to the lockdown. At a time when the political economy of conflict zones is extensively studied across the world, it seemed absurd to me that a liberal arts university that prides itself on “diversity and inclusion” would turn me down for lack of money.

A lot has been written about the homogeneity of students on campuses, especially private ones like Ashoka and O.P Jindal, but it seems that nothing has changed. In March last year, a survey report was published by The Edict – an independent student newspaper at Ashoka University. According to this report, 63.16% of the students in the flagship Young India Fellowship programme had an annual family income of Rs 10 lakh, followed by students with a yearly family income of Rs 30 lakh.

There are many reasons for this disproportional representation. In my case, the lockdown in Kashmir robbed me of this opportunity. It was the false claims of diversity and inclusion which made me spend days and weeks writing essays and preparing for interviews, only to be disappointed in the end.

I do not want to discourage others from applying to any university. However, it is imperative to point out that reforms are needed to make processes such as these more accommodating and empathetic towards marginalised students.

Maknoon Wani is a final year student at Delhi School of Journalism, University of Delhi. He also runs kashmirinnovators.com – an online repository of scientific and social research undertaken by Kashmiris. He recently created tiny.cc/jktaeleem – a

Featured image credit: Nathan Dumlao/Unsplash