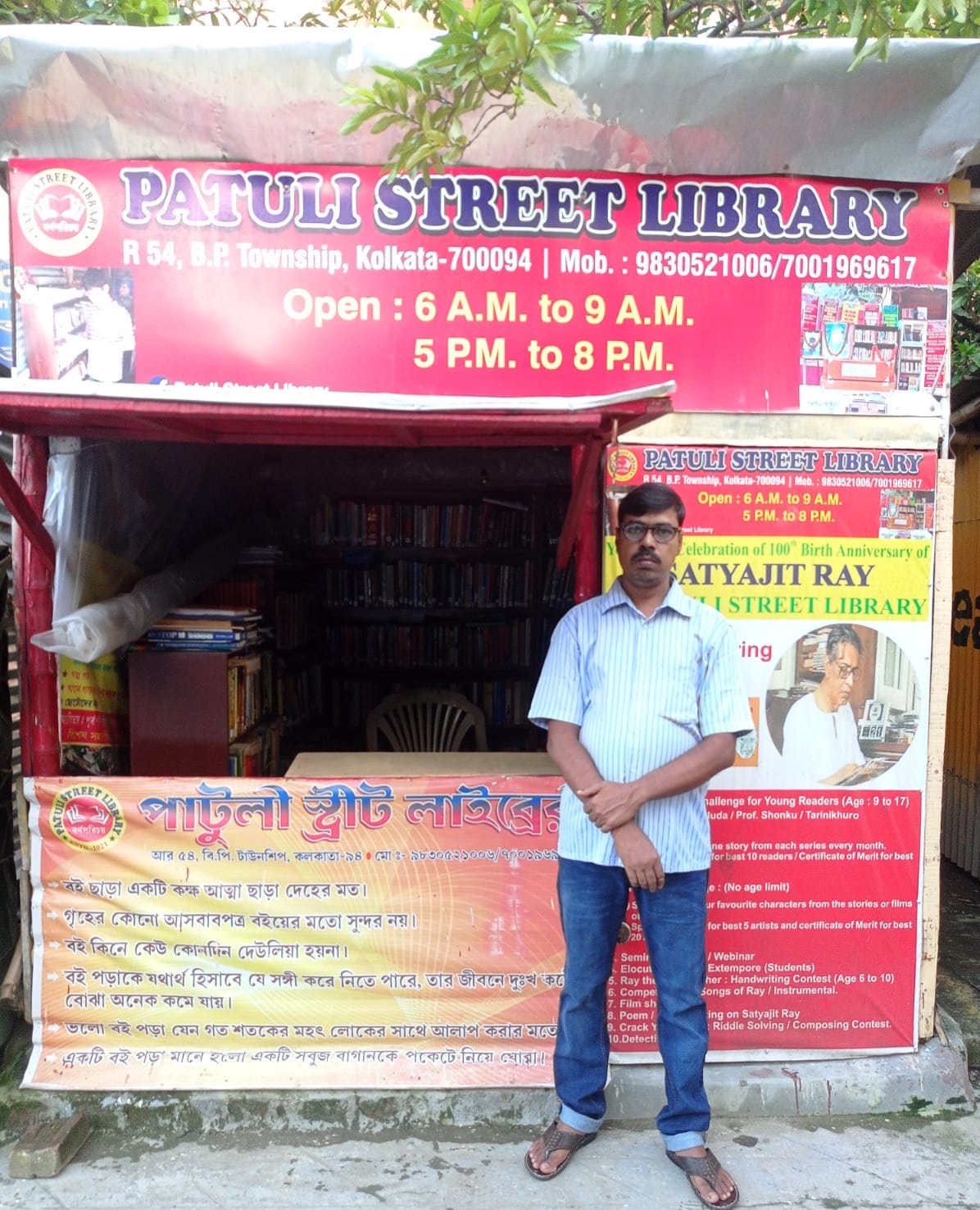

“The only thing that you absolutely have to know is the location of the library” stands true for Patuli Street Library (PSL) at Patuli, Kolkata. Hidden amidst a row of makeshift shops on the margins of the pavement which borders a residential complex, a technology and management institute and a park, this library is one of its kind in the city. Its location makes it so inconspicuous that it can be mistaken for another wayside stall until one notices an old refrigerator stacked with books – which in itself is almost a leaf out of fiction.

Though I had read on social media about Patuli Street Library, I had no inkling of the extent of work PSL has been engaging in. It was during our visit to the city this summer that I got curious, when my septuagenarian father, a regular visitor to the library, introduced my child to its collection. Seeing my child running to PSL almost twice a week, I realised the potential of a street library and the kind of enthusiasm a free library can instil in a child.

It was on a humid summer evening that I happened to meet Kalidas Halder, the founder, outside his dimly-lit library. He had just returned from Madhukhali in the Sundarbans, after conducting a theatre workshop for children. The brief conversation that I had with him revealed the extraordinary zeal of an otherwise ordinary high school teacher, steadfast in his promise to keep the concept of the library relevant and the value of books alive among children across class, in a technology-driven world.

When sights of death and of thousands walking home were troubling us and the sudden school closures led to a shift to online modes of learning, jeopardising the education of thousands of disadvantaged children, Kalidasbabu and his elder son, Kingshuk (then a Class 9 student), were determined to reach out to those in distress. It was not difficult for them to perceive the importance of reviving reading habits among children, particularly at a moment when the young and the old were gripped by hopelessness or had become victims of unprecedented levels of screen time.

For them, providing books (ranging from academic books to fiction, dictionaries, classics and comics) to those who lagged behind due to internet inaccessibility and poverty and those who needed to be weaned from the virtual world, and its often poor content, was the easiest option. Since the family already had a large collection of books, they decided to set up a library with a difference — a street library — one without frills, one that is open, free and based entirely on trust.

Also read: How Zimbabwean Artist Kudzanai Chiurai Has Reinvented the Idea of a Library

Even though it started as a family initiative, the neighbourhood came out in support of it. The local grocer lent his shop space to stack the first lot of books and when nobody was around to help a customer, the nearby presswallah substituted the mentor. Several volunteers of PSL have never received any formal education, but they believe in the value of education which motivated them to join Kalidasbabu.

It is no wonder that for Kalidasbabu his library ‘is a family’. Besides his wife, a couple of retired elders of the locality contribute towards the running of this library, from where anybody can borrow a book for a month; nobody needs to become a member or pay. While PSL’s target readers are 8 to 18 years old, a large number of visitors are senior citizens.

In Kalidasbabu’s own words, as much as he wishes his library to act as an “icebreaker” for children whose lives are limited to gadgets with hardly any scope for socialisation, or, for those who have absolutely no access to books, he wants the same for the elderly too who are increasingly living a lonely and secluded life, away from their children and relatives.

The concept of a street library has been popular across the world and Kolkata is not new to street libraries. However, what makes PSL unique in its model is that unlike many such street libraries across the country, PSL was not a result of any government intervention. It is run entirely by an individual with no financial ties with NGOs, nor does it rely on any external funding.

Kalidasbabu puts in 25% of his personal income to keep the library going. The library has grown manifolds over the months. It now boasts of 10,000 (from its initial 600) books on its shelves housed in a tiny shack. It is a rich repository of both Bangla and English books with a special focus on children’s and young adult literature. Not only do well-wishers donate old books, but some of them have also added new ones to the collection.

Kalidas Halder in front of Patuli Street Library

PSL aims to make children with basic reading skills read at least one book per month. Knowing well that a book may not be as attractive as a gadget and children have to be wooed to read, it began organising theatre workshops, storytelling sessions, and skits and formed a drama club. These would inculcate reading habits, social values and empathy among the uninitiated or disinterested readers. To establish reading as a pleasurable experience, PSL has gradually evolved as a hub of literary and cultural activities. Recently, a new space has been acquired in Patuli, where ‘sahitya aashor‘ (literary meets), storytelling and book reading sessions would be held regularly; it would also double up as a children’s reading room.

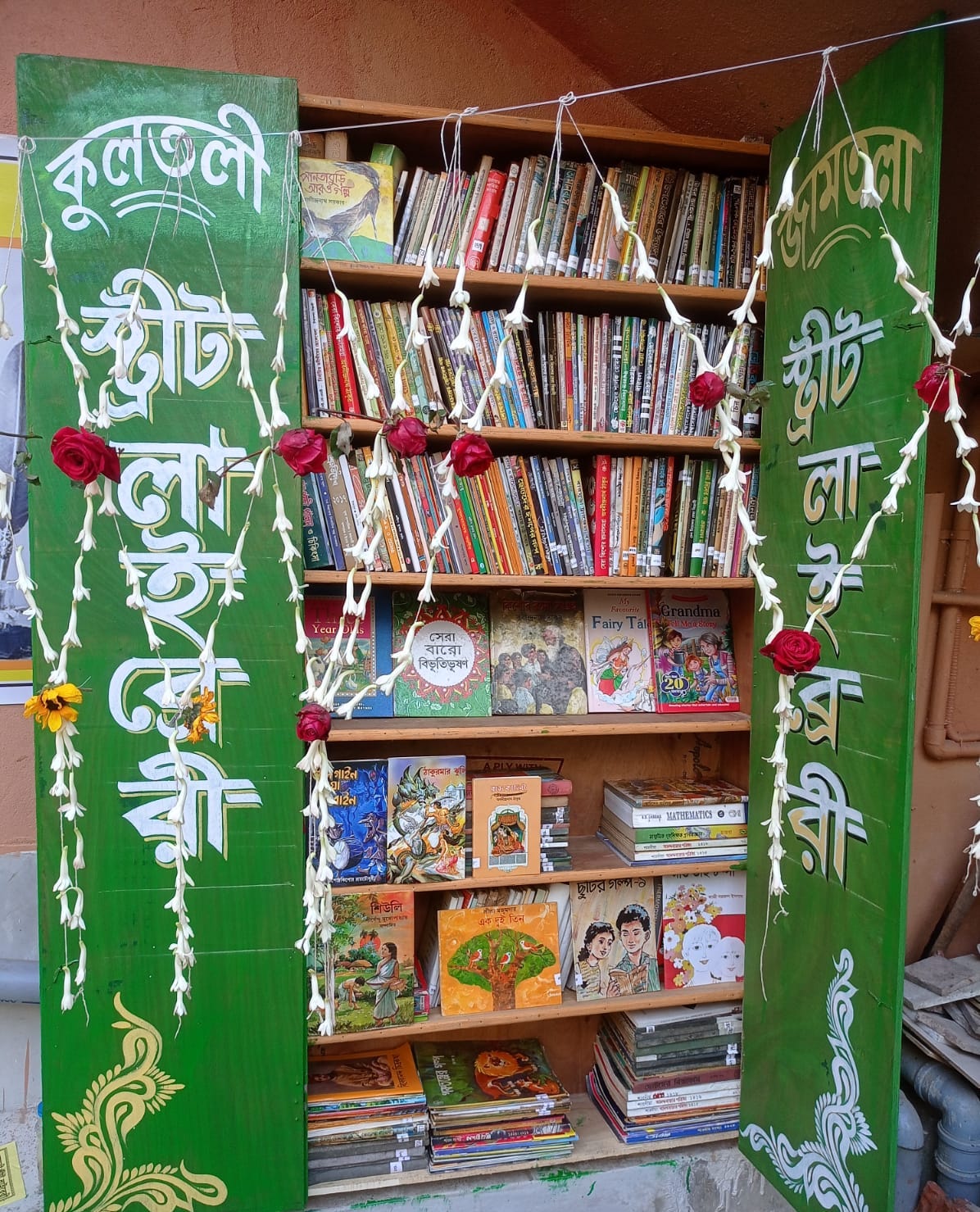

Tarapada Kahar in front of his grocery store. The old refrigerator is stacked with books.

A journey which began only about a year and a half ago, inside a humble neighbourhood grocery shop’s shelf and a defunct refrigerator, has now turned into a silent movement. Being a voracious reader himself and a member of popular libraries in the city, Kalidasbabu realised that such elite spaces are beyond the reach of the marginalised children. With a deep understanding of the unequal world we live in and the socio-economic and linguistic inhibitions and barriers which restrict such children from using those libraries, Kalidasbabu set out to ensure their right to read through street libraries (which he believed was the sole alternative).

His experiences during the pandemic and later the cyclones which struck Bengal strengthened his resolve to transform the lives of the deprived children through books. When Cyclone Yass hit Bengal in 2021, the PSL volunteers carried food to the cyclone-hit villages of Sundarbans and Digha (Midnapore). During their interactions, the villagers expressed their inability to access books. PSL did not disappoint them. On the subsequent visits, they distributed 4000 books among the poor yet inquisitive children of those far-flung villages.

PSL’s mission is to open 100 street libraries in remote areas in Bengal and spread the joy of reading among those for whom a library full of books is only a distant dream. In fact, PSL is looking for prospective mentors outside Bengal, who would be interested in building street libraries. It donates an initial stock of 400 books (250 new and 150 old books) and a few shelves to whosoever desires to open a street library.

Continuing in its mission to reach the unreached, it has already managed to help set up six such libraries not only in and around Kolkata but also in the extremely backward pockets of South 24 Parganas (Madhukhali, Lahiripur – Sundarbans, Shaktipur – Bokkhali and Kultali). The process to open the seventh one in the tribal area of Belpahari (Jhargram) among the Lodha community is underway, and is likely to become functional in August.

Books being distributed in the Cyclone Yass affected areas; Street libraries were inaugurated at new locations.

Besides helping open similar street libraries away from the city and building a strong community of readers ( 70-80 regular users) around the township, PSL has extended its presence through a temporary mobile library called Milestone. To encourage underprivileged children to read, cope and continue their education despite the hardships they are facing due to the pandemic, PSL’s mobile library visits nearby slums at specific hours twice a week. The vehicle used for Milestone is an old car offered by one of its benefactors.

It is working towards procuring a permanent mobile library to help cart books to children residing in other localities. Apart from offering library facilities to schoolgoers, PSL has also been successfully running a free coaching centre called Barnaparichay for needy students of Classes 9 to 12, studying in Bangla medium schools. The space for the classes has been provided by Dinabandhu Andrews Institute of Technology and Management.

Children are seen borrowing books from ‘Milestone’ at Goragachha slum (near Garia Station).

To maintain the quality of teaching PSL has brought together a team of committed teachers and researchers who are teaching free of cost. In the coming days PSL, aided by Kalidasbabu’s former students, is also planning to hold science exhibitions and talks around science to fight superstition and cultivate scientific temper among the young.

Also read: Why I Like Reading Without a Purpose

In an age when nobody has time for anybody and the future of libraries looks bleak, PSL stands firm against the onslaught of online libraries and ebooks. The progress it has made in a short span of time is noteworthy and the response it has garnered from its benevolent patrons has been overwhelming. However, they are conscious of the challenges that street libraries tend to face in the long run. Sustainability is an issue, and, to make the new librarians self-reliant and to help their libraries become self-sustaining, Kalidasbabu and PSL volunteers spend a considerable amount of time guiding them.

Similarly, language has the potential to act as a hindrance in certain areas and to overcome the same PSL makes sure that the libraries are well stocked with books in the language, mostly in Bangla, used by the local people. Loss of books due to theft could be another possible problem, but Kalidasbabu is unperturbed. PSL seems to have taken an innovative stance by not only placing the entire trust of keeping and returning the books safely on the readers but also in believing that whoever would steal a book would do so out of sheer love for the book!

Amidst all the violence, injustice, and pessimism around us, PSL’s unswerving determination to turn crisis into an opportunity is exemplary. Even though the pursuit of this kind is often fraught with obstacles and uncertainties, PSL emerges as a reservoir of humane values in an increasingly inhuman and lonely world. As we look beyond the pandemic and move on without forgetting its lessons, Patuli Street Library’s story comes across as one of hope, resilience and solidarity.

Devjani Ray teaches at Miranda House, University of Delhi

All images have been provided by the author.