Tonnes of essays, op-eds and books have analysed the phenomenon called Shah Rukh Khan as the poster boy of India’s liberalisation. They’ve dissected how he liberated the Indian middle class from the archaic moralism of past decades. And yet, the story rewrites itself with every new interview, every honorary doctorate lecture, every TED Talk, a David Letterman interview or interactions with Amazon and Google chiefs Jeff Bezos and Sundar Pichai.

The actor once talked about being employed by the myth called Shah Rukh Khan. It’s this mythical element – a living superstar who self-admittedly performs “over the top actions” for his fans as he works for the myth – that makes him a part of our collective and individual consciousness.

So, every #MySRKStory — that trended and peaked on his birthday on November 2 as a reassertion of India’s love for him following the arrest and subsequent bail of his son Aryan Khan in a controversial drug case — tells a uniquely personal story, perhaps reigned in by how one imagines the “Mohabbat Man”.

Growing up in the 1990s, Khan came like a breath of fresh air or an agent of change — his intoxicating voice, dimpled smile and unbridled charm stirring the first rush of a romantic crush. But this essay is not about my being a Shah Rukh Khan fangirl – which in itself is a story about the coming of age of girls whose desires, wishes and dreams have been known to be repressed by custodians of honour, morality and patriarchy.

The 1970s belonged to Amitabh Bachchan’s ‘Angry Young Man’ with the booming baritone symbolising his overbearing masculinity. The latter half of the 1980s saw a transition into Anil Kapoor’s Mr India hero persona, who was comfortable in invisibilising his selfhood and then Aamir Khan in Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak as the young, cute, funny heartthrob.

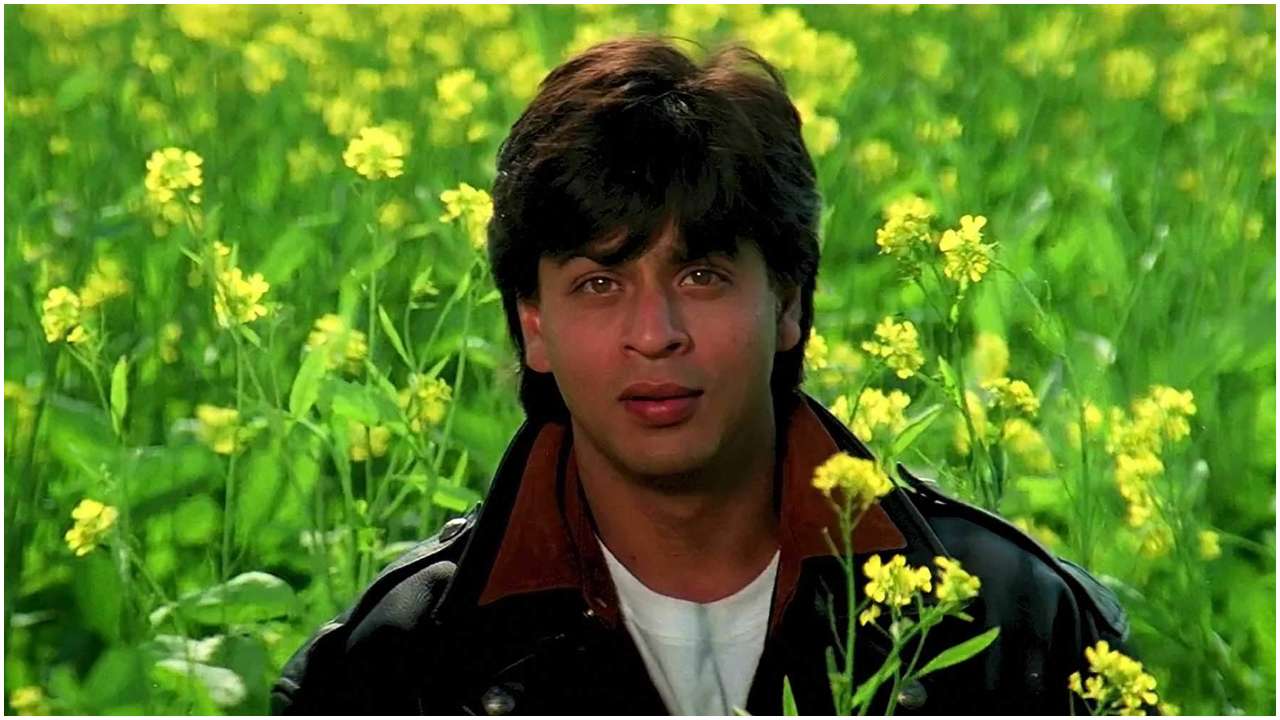

Shah Rukh Khan in ‘Deewana’. Photo: IMDB

But then came Shah Rukh Khan’s Deewana in 1992.

Playing the namesake hero, his entry in the second half of the film after the supposed demise of Rishi Kapoor’s character announced the arrival of Shah Rukh Khan as a symbol of New India, the hero who combined the raw and rough edges of masculinity with deep-rooted feminine pathos within a commercial template. The aggression with the vulnerability, the smile with the tears, the moody volatility with the softness of pain and longing. The hero who desired and whom the heroine — and a whole generation of Indian girls — desired.

The Deewana gaze heralded the gaze of the passionate lover — inward-looking and evoking depth and intensity, more soul-searching than body-ripping. It was manly, but not built upon the male gaze that routinely objectified women or sought ownership of the female body. It was only fitting that Divya Bharti’s Kajal crowned the lover boy as ‘Deewana’ in the title song of the film as this hero – who was out to make his lady love happy – considered the woman’s approval in what he did as important.

The Raj-Raju-Rahul saga continued with Khan fashioned as the hero who offered himself in love and to be loved in a succession of films. Even if Raj in Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995) was obsessed with the palat-palat gimmick, insisted on the girl’s father as the authority in her life from whom permission must be obtained – pegging sanction of love as patriarchal in a man-t0-man dealing – and crossed boundaries of the body especially as one would rightly acknowledge it in the post-feminist #MeToo times, running away with Raj surely felt like a whiff of freedom despite the film title suggesting that it was Raj who would whisk ‘his’ Simran away.

The mustard fields where Raj stood with his arms wide open was everything that Hindi cinema’s cult of mard or mardangi wasn’t until then. There stood a charmer who was beauty over brawn, mind over body. In the times that it was made, DDLJ signalled the arrival of the new-age hero, the modern, confident and compassionate Raj who could be cocky at times but who would offer a revisionary manhood to the likes of Kuljeet, the hefty and uncouth, desi “gabru jawans” who wanted to have “fun” with women in foreign lands while their perfect Indian wives waited at home. A Raj who would rather spend time with the women of the household, doing chores and singing, or helping an aunt select a lovely sari for herself than sit with the men. A Raj who would cry and would not assume his right to call Simran’s younger sister by her nickname in any manly entitlement.

Simran rose above the oppressive chain of control. Raj was Simran’s choice. And as every Simran rejected the nostalgic motherland narratives of their Baujis and the regressive Kuljeets of those hegemonic worlds, somewhere it was hoped that there would be a Raj to stand up for Simran’s choice. The lover who would go through a series of humiliation for her without making it about the fragile male ego.

It was also during the 1990s that before the birth of Raj, Khan was the cold-blooded murderer Vicky/Ajay in Baazigar (1993) and the obsessive stalker Rahul in Darr (1993). Blurring the lines between good and bad, Khan embraced the anti-hero graph with a toxic strain.

This was a novelty in his time, something he credited to his unique looks – which by his own admission was not a “regular, sweet boy face or an action hero’s face, it is a mixture” – enabling him to slip into a Deewana or comic roles like in Chamatkar (1992).

That’s not all. There’s the musically-inclined happy-go-lucky Sunil too in the romantic comedy Kabhi Haan Kabhi Naa (1994), who realises and accepts that Anna will never love him no matter what he does. The journalist Amar in the avant-garde Dil Se (1998) who fails to understand how his one-sided love and his attempts to oversimplify Meghna’s life were built on ideas of entitlement, access and privilege until his final act of surrender. The anti-hero roles perhaps set wrong examples, especially in a country that has a Romeo-on-the-streets culture. In the adoption of a less than righteous path to love, revenge and redemption, Khan at times combined oddities and excesses in his hero figure without preachy overtones.

Also read: In Appreciation of ‘Kabhi Haan Kabhi Naa’ and Its Flawed Hero

Through the pre-and-post Raj romance era in Hindi cinema, the Shah Rukh Khan persona kindled a hope for romantic alternatives to age-old censorship of female desire, sexuality and agency. A belief that women treasured deep in their hearts that they didn’t need to settle for anything less than love in life or marriage, and that a relationship should not be a product of banal conventions, reverence for the patriarchal need to protect a woman or out of a fear of not being able to find the one who would desire her and make her feel special. With his big, brown eyes and forehead-caressing mop, he struck a chord that perhaps it is the right of every woman to feel loved and in fact, demand that love, and if need be revolt for that right.

In much of his earlier filmography, Khan effaced his Muslim identity under the Hindu lover boy-guise so much so that he is said to have popularised Hindu rituals of Karwa Chauth and glamourised wealthy funerals in his movies. That was until he played the ‘tainted’ Kabir Khan, who redeemed himself as he coached the Indian women’s hockey team to victory in Chak De! India (2007). A decade later came the first-of-its-kind and beautifully enacted, gentle-hearted badass bootlegger namesake hero in Raees. In My Name is Khan (2010) set against the backdrop of the 9/11 attack, Shah Rukh’s Rizwan Khan (Shah Rukh Khan) with Asperger’s syndrome sets out to meet the US president to tell him that yes, his name is Khan but he is not a terrorist and not all Muslims are terrorists.

Mouthing the dialogue “Khan, from the epiglottis” and wearing his Muslim identity with pride and authenticity, Khan on and off the screen still seems to be saying it to an India of today that his name is Khan, he is Muslim, Indian, Indian Muslim, an Indian global superstar and a Muslim Indian superstar.

Brand of love in times of Hindutva hate

It is this resonance of Khan’s secular Indian identity with an inter-faith marriage with his Hindu wife Gauri, the epiglottis hallmark and his signature adaabs that run parallel to his superstardom, making him rise above the bhakt-unbhakt, Hindu-Muslim, regional/national, Hindi-Urdu-English, male-female-queer, masculine-feminine, India-Bharat divides; above the narratives that are made to run like barbed wires of partisan identity in today’s climate of polarisation.

Once an icon of the “Yeh Dil Maange More” generation, Khan today is an icon of an India that needs the redemption of love. Marrying meaning with metaphor and some madness, it is startling that two decades later, Khan still propels an aspiration for a more modern India that is being remoulded through a narrative of hate drawing upon imagined or better forgotten historical pain and trauma.

“Our religion cannot be defined or shown respect to by our meat-eating habits. How banal and silly is that,” said Khan in an interview to NDTV as he spoke with journalist Barkha Dutt on how religious intolerance would take India to the dark ages.

Star and person Shah Rukh Khan is that image of India which is not anchored in hate and misogyny but in inclusive tales of respect, love and warmth. At a time when love itself is hyphenated with jihad, where Muslim men are charged of seducing Hindu women in order to convert their religion to Islam, with those in power punishing the former for being Muslim and infantilising the latter while curbing their agency of choice, it is perhaps ironic and beautiful that India’s biggest cultural export to the world in the post-liberalised world is Shah Rukh Khan, the eternal lover.

And whose “naked gaze of passion” age has yet not diminished, even though he has self-consciously alluded to himself as resembling his wax statue of late as age catches up. As Khan personifies the man with the addictive power of love, whom women across faiths and languages swoon over, he must be seen as more dangerous for the Hindutva project than a man holding a gun.

The articulate and witty Khan has stood for how intellect, compassion and empathy could still be part of a commercial hero’s public persona, as much as the norm-defying cartwheels and humour. How warmth would not necessarily dilute his brand, hero image or worse manliness.

With a power to make love his biggest brand value and lending himself to female desire, Khan’s warmth shines through even in the self-parodic arc of the ‘Mohabbat Man’. Like it does when the shy Everyman Surinder Sahni in Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi (2008), is respectful towards every meal his wife cooks and is comfortable holding her handbag while riding behind her on a motorbike. There’s humility in love.

Also read: From the Targeting of Shahrukh Khan’s Son to Urdu, At Play Is Insecurity of the Hindutva Mindset

Remembering his father as “the most successful failure in the world” as he read a touching extract about a visit he took with his father to Peshawar, and his “straightforward” magistrate mother, Khan said, “I imbibed both sides and became a very pragmatic, practical poet.” He was speaking at the Think 2012 session with former Tehelka managing editor Shoma Chaudhury at a session titled ‘The Solitude of a Superstar: The Public-Private Journey of a Dream Catcher’.

As he read from his own writing ruminating on loneliness while drawing on the poet W.H. Auden, Khan read at the end that “Adulation has the distinct quality of isolation”. The duality of the poet and the pragmatist is evident in how he went on to talk about having no qualms about living the good life. And yet how he cherished “the laughter of a lonely, struggling mother and her strange son” at a scene in one of his movies.

In that happy duality or between the extremes perhaps lies the magic and myth of Shah Rukh Khan who describes himself as a shy person and his children as his best friends and who joked about changing his name to Akshay Kumar at an NDTV show hosted by Dutt. The topic was “Muslim identity” and Khan was hailed as an example of India’s lessening prejudice against Muslims as he didn’t have to change his name unlike Dilip Kumar, and in all earnestness, the actor said he wouldn’t have changed it ever.

Akshay ‘Bharat’ Kumar with his trademark pop patriotic and jingoistic films has refashioned himself as the poster boy of Narendra Modi’s India, interviewing the Prime Minister on mangoes and mother. In the process of co-opting of the Hindi film industry by the ruling regime, the likes of Kumar have fuelled the Hindi-Hindu and patriarchal narrative in sync with the current majoritarian imagination.

It was in 2015 that Khan took a public stand for Mohammad Akhlaq, a Muslim man, who was beaten to death by a Hindu mob. Soon, he was trolled and his nationalism questioned. Since then, there have been more silences.

We love Khan’s dignity. We love his charm. We love the adaab. We love the open-arms pose. We love Khan flying the tricolour in a cricket stadium. That’s the India that makes us proud. And we would not like Khan to be silenced.

Sanhati Banerjee is a Kolkata-based journalist.

Featured image credit: Pariplab Chakraborty