In 2008, during the Amarnath land row controversy, schools in the Valley remained closed for over two months. Similarly, after Burhan Wani’s killing in 2016, schools in Kashmir reopened after eight months.

Then, after the complete lockdown post August 5, 2019, children returned to schools seven months later only to be locked up once again inside the four walls of their homes after the Centre announced a nationwide shutdown in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Needless to say, long patches of separation from school aren’t novel for Kashmiri children.

What is unfamiliar, however, is the pretence of normalcy brought about by the introduction of ‘online classes’ in the Valley.

Following the Centre’s announcement, Kashmir’s private schools unanimously decided to resume classwork via the internet. It isn’t the first time that private schools have tried to compensate for the ‘loss of academic sessions’ due to cycles of violence in the Valley. However, the government’s callous copying of the old ways is ridden with a host of shortcomings.

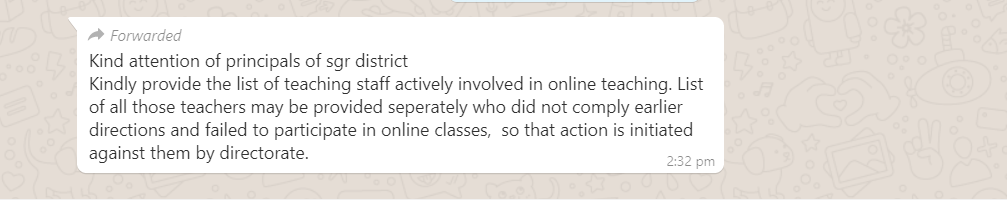

In early April, the government passed an order directing public school teachers to start classes online. It seems that the order has been passed rather informally, in the form of phone calls and text messages to the school principals/headmasters. The directorate of school education Kashmir’s official website does contain any information in this regard. Teachers say that they learned about it through personal calls among colleagues and WhatsApp groups.

“I heard about this order a few weeks ago via one WhatsApp group,” says Hameedah, a high school teacher in Srinagar.

Figure 1. A WhatsApp forward asking teachers to start online classes, waring of repercussions otherwise.

The directive (if any), has been formulated without consulting the school administration and the teachers who are actually expected to carry out all the formalities. Bringing them on board would have certainly made this process more feasible for both, teachers and students.

It is, therefore, a reflection of the lack of systemic planning as it fails to consider the obvious unequal access of internet or even the means for accessing it for students. Furthermore, the teachers are not well equipped with the technical know-how of e-learning, a relatively alien concept for them as well as for the majority of the students.

Also read: Delhi University: Online Lectures and Accessibility

This rather ‘enforced digitalisation’ of education has come at the cost of utter confusion and uncertainty. Teachers are concerned about the insufficient number of students they are able to reach during classes. “There are 14 students in my class, only three have access to both, a smartphone and internet”, said Shabnam Parveen, a govt middle-school teacher in district Budgam. “I don’t know how Google classroom works and neither do my students.”

The teachers I spoke to told me that they don’t have books at home, and therefore they have no choice but to step out despite the lockdown.

Their anxieties show a sense of despair as these classes have been made compulsory. It brings to light the continued ban on high-speed internet, as it enters the ninth month, making it the longest ever in history. Despite the slow-internet speed in the valley, expecting an already broken way of teaching to be effective is condescending and questionable.

And for the students who are unable to go online, there are not alternative plans.

“My teacher used to teach us so well in class, now she only reads aloud three sentences and we are done… They give us way more homework than we would get in class. I hate it, I wish we were in schools or we had video classes instead of audio,” says Marwah, an 11-year-old student.

At the university level, students are finding it extremely hard to deal with the academic pressure as the only source of teaching and learning is WhatsApp audio notes and short videos, which take long hours to upload and download on 2G speed internet. In all likelihood, they will miss these semesters, as has been the case for the past three years in the Valley.

Interestingly, a parallel of this move could be drawn with the government’s earlier attempts of persuading people to send their children back to school post the reading down of Article 370 in an attempt to present a picture of ‘normalcy’ in the Valley. It doesn’t therefore come as a surprise that students are now expected to take lessons via the All India Radio, as per the recent statement from the Directorate of School Education, Kashmir.

The lockdowns in the Valley has already taken a toll on the mental health of people in Kashmir and this inadequately planned guidelines are further putting them at the risk of increased anxiety and stress. There is a need to adopt more reasonable and thoroughly researched plans of action by the education department in the Kashmir.

Mariyeh Mushtaq is from Kashmir and she is interested in researching and documenting the socio-political aspects of militarisation in South Asia, more specifically in Kashmir. She recently completed her masters in Gender, Sexuality and Culture at Birkbeck, University of London.

Featured image credit: PTI