“What’s the point? You can do everything digitally now?,” Baba asked me in 2017 when I showed him my first instant film camera – a Fujifilm Instax 210 wide – which I bought with dollars earned from my on-campus job. Always part of my hand luggage was a cardboard box shoehorned with polaroids and postcard-sized photographs; my pre-flight takeoff routine included skimming through them.

“Ask me this question again in a few years Baba!,” I smirked.

I lived in New York for four years between 2014 and 2018). #FilmIsNotDead they said, but did they tell you how expensive analog film is? My fathers’ question is valid – why did I invest in such an expensive endeavour since I already owned a digital camera?

How was I to explain my photophilia, my love for the tactile nature of photography, and all things analog? There is a seeming permanence to the touch of film chemically altered by photons.

During the spring of 2015, I witnessed my first snowstorm and also got a sinus infection. I didn’t own a polaroid yet, but clearly remember what it felt like to watch snowflakes descend onto the window sill. And that’s when I decided to buy one for my best friend – a Fujifilm Instax mini 8, which produces credit card sized images.

As a child, I memorised fleeting scenes I wished I could record like the fluttering wings of a blue monarch butterfly. I hoped that if I blinked at the right time (like pressing the silver button at a decisive moment) the scene would stop – time itself would stop! Who knew this habit would come in handy while capturing moments as I started making photographs using professional equipment, a decade later?

Have you ever deleted an Instagram direct message? Long press, touch unsend and poof – the moody grey cloud siphons your text away with nothing but white space staring back at you. Unless you burn or throw it down the chute, Polaroid photos last the average human lifetime. In fact, as of May 19, 2020, I confiscated one from my brother because he left it in his study table drawer. How dare he let the precious 3.4 by 4.3 inch frame get scratched? A keepsake for future, I would definitely place my polaroid camera in a time capsule.

Also read: Buri – My Grandmother’s Eternal Lockdown

In college, I could sneak in my not-so-small Fuji to friends’ homes, using it when “the moment” appeared, for the flash screams surprise at evening parties. I clicked to capture not “for the gram”, but to remember beyond college.

To French philosopher Roland Barthes cameras are clocks for seeing. To me, photographs are ticking hands chasing each other. Each Polaroid informs the next, patiently waiting: one push and the negative fused with the positive births itself to the world.

Polaroids are neither proof, nor document, but the grammar of my grief.

Sometimes through negatives you see what positives cannot show – this holds true particularly in case of analog photography, and beyond. There was a time when gently pressing the circle on your smartphone screens didn’t suffice – even before you could “click” or press the “shoot” button you had to “read” the light meter, “wind” the film and “compose” through the viewfinder. There was no flat digital reproduction of the frame or “snapshot” as we know it today, let alone apps on the internet that modify your images within seconds. To see an image, you had to make it – literally produce it in a darkroom, there was no instant gratification.

At the age of 18 (in 2014), light took on new meaning for me. Thanks to my analog black and white photography course, I understood that it was okay to make mistakes; that there was room for errors. Often negatives would get damaged by too much fixer or because I was still learning. The option to ‘burn’, ‘dodge’ and physically ‘crop’ an image existed, each image was work in progress.

Shiny side up, I had to constantly remind myself, while inserting the thin negative film onto the loading reel. It was okay to get imperfect negatives (for the first ten rolls of film at least!).

In the developing room, you had to blink in blackness, feel the rim of smooth bi-perforated 135 millimeter film, before carrying out chemically sensitive, time-bound tasks under an orange-red “safe” light. Then came the herculean task of developing prints with impending risk of ruining your light sensitive silver gelatin paper. Initially, it took me six hours of trial and error (on average) in the darkroom to make 8.5 × 11 inch prints! But that’s not all, my roommates often complained, “Your clothes reek”, (sorry, not sorry, that was the acid in photo developer). At the lair of beauty rest parts we can neither accept nor reject, I thought jokingly.

Also read: Lockdown Paves the Way for Insightful Conversations on Photography

Technology could see greater detail than the naked human eye, so I didn’t care if my clothes had acid burns (although in retrospect, I do miss my cobalt blue shirt very much). As someone who doesn’t remember what it is like to have naturally perfect vision (I started wearing glasses at the age of four), I deemed photography with high regard. The grain and grit that comes with black and white photography is something I chase even today. I don’t have darkroom access in India, but I treasure my prints and more importantly, the thick folder of negatives, currently gathering dust at home in Delhi.

To me “observe” is a state of mind and not just a verb. In the words of photojournalist Dorothea Lange, “The camera is an instrument that teaches people to see without a camera.”

My father, a medical physicist, sees light in a totally different manner. In March 2020, after going through 20 odd albums, I found a polaroid of him at a science conference, from at least 10 years ago. I called out for him, and he asked me why the room was in such a disarray.

I didn’t have an answer, the mess spoke for itself – I handed him the polaroid.

Subhashree Rath graduated from Sarah Lawrence College in May 2018 with a background in Visual Anthropology and she believes in the power of photography, storytelling, and active listening.

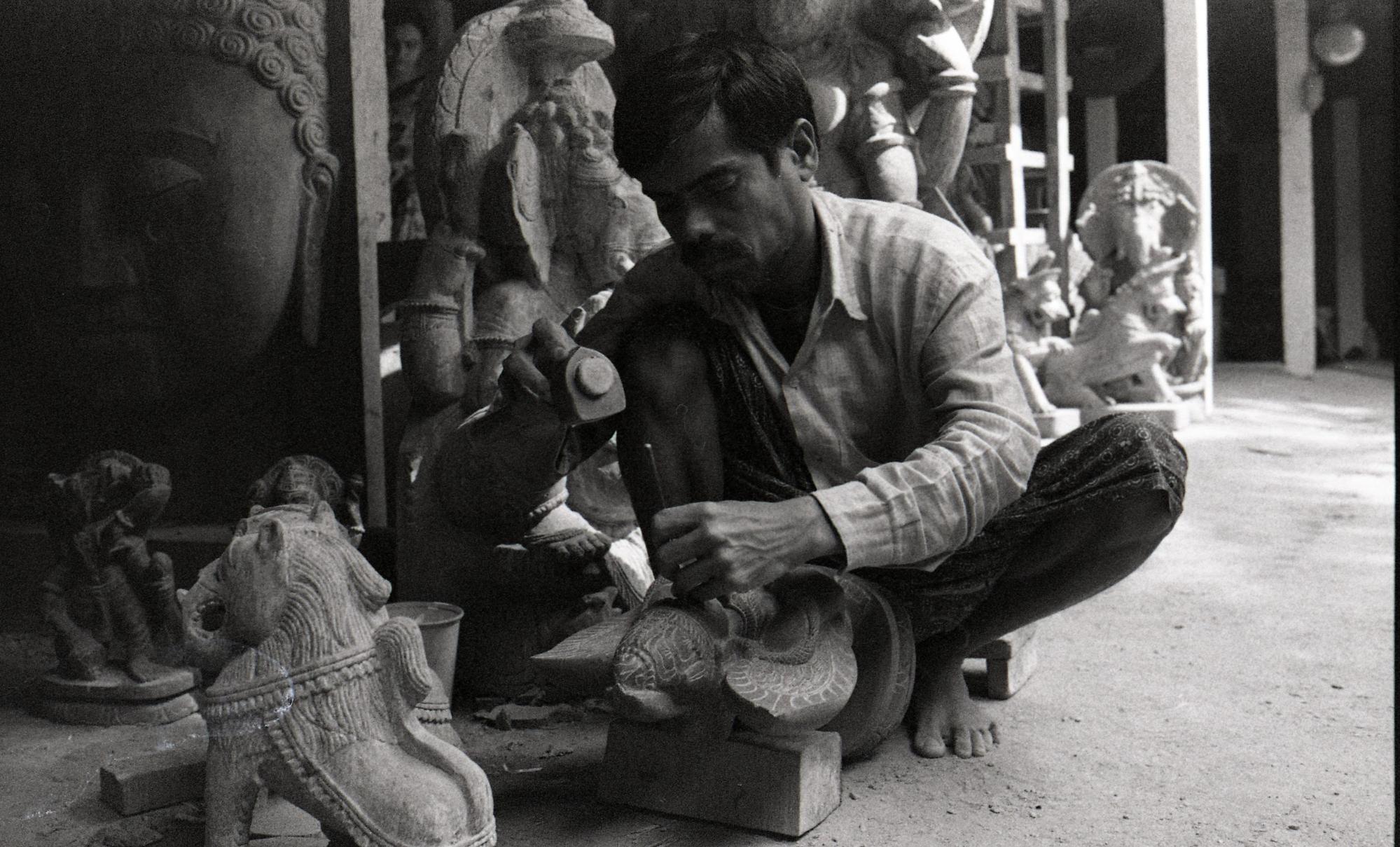

All photos provided by author