“Bhaiyaji, library band ho gaya hai (Brother, the library has been closed).”

We stood outside the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) in New Delhi in the scorching mid-day heat of April 2021, pondering over the looming crisis. It was even more threatening than the expressions of the security staff, who informed us about the closure of the specified institutional archive. We were clueless about how to proceed at the moment, and were left with no other option than to board a Delhi Transport Corporation (DTC) bus and head to our campus hostel at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU).

The fourth and final semester of postgraduate studies at the Centre for Historical Studies, JNU, involves an academic component of writing two original research papers. Our fourth semester began in February 2021. During this period, we started to use the services of the aforementioned library to hunt for primary and secondary sources with regard to our fields of research. However, the intensity of the second wave of the coronavirus pandemic in India resulted in the abrupt closure of almost all institutional spaces by April 2021.

As we submitted our research papers by June 2021, we sincerely felt that we could not do justice to actualise the potential of our research interests and capabilities. This was very crucial for us because we intended to develop, build and expand upon our postgraduate research while pursuing our doctorate degrees.

We were further led down a rabbit hole of difficult challenges in the Indian higher education system by another series of events. By October 2021, a problem much larger in magnitude engulfed our lives. It was no longer an issue of the pandemic, but rather it had quickly evolved into the phase of the ‘post-pandemic’. The government authorities tried their best to ensure the continuation of our woes in an unabated manner.

It is important to note that there has been a constant reduction in the number of seats allocated for PhD research, especially in subjects such as ‘historical studies’, ever since 2017.

Also read: JNMF Asked to Vacate Teen Murti to Preserve Legacy of ‘Other Former PMs’: Centre

It is almost impossible to cover the cost of pursuing a PhD degree for a large majority of students in central universities (such as that of JNU), who hail from marginalised social backgrounds, without the grant of fellowships. Further, we were jolted by the information that they were keen on considering the retraction of non-NET (National Eligibility Test) fellowships, which are provided in many Indian universities to research scholars who do not have a Junior Research Fellowship (JRF).

With the possible retraction of non-NET fellowships, we were now left with no other alternative but to clear the cut-offs for the JRF programme, which is constituted within the NET examination. But the thorny academic journey continued on. The NET examination was supposed to be held within the month of October 2021, but it got postponed several times and was finally held in December 2021.

The long process of securing PhD admissions at JNU, through the entrance examination and viva-voce interview, had begun by September 2021, and since we did not already have a JRF, clearing the entrance examination is a mandatory requirement in case one needs to directly qualify for a viva-voce interview. The assessment of PhD admissions through the viva-voce interviews is bound by several real-time constraints, and hence, it does not stand on favourable and justifiable grounds on the historical rigour, skills, and acumen of an aspiring candidate.

These factors made us quite apprehensive about even thinking of applying for a PhD in the first place.

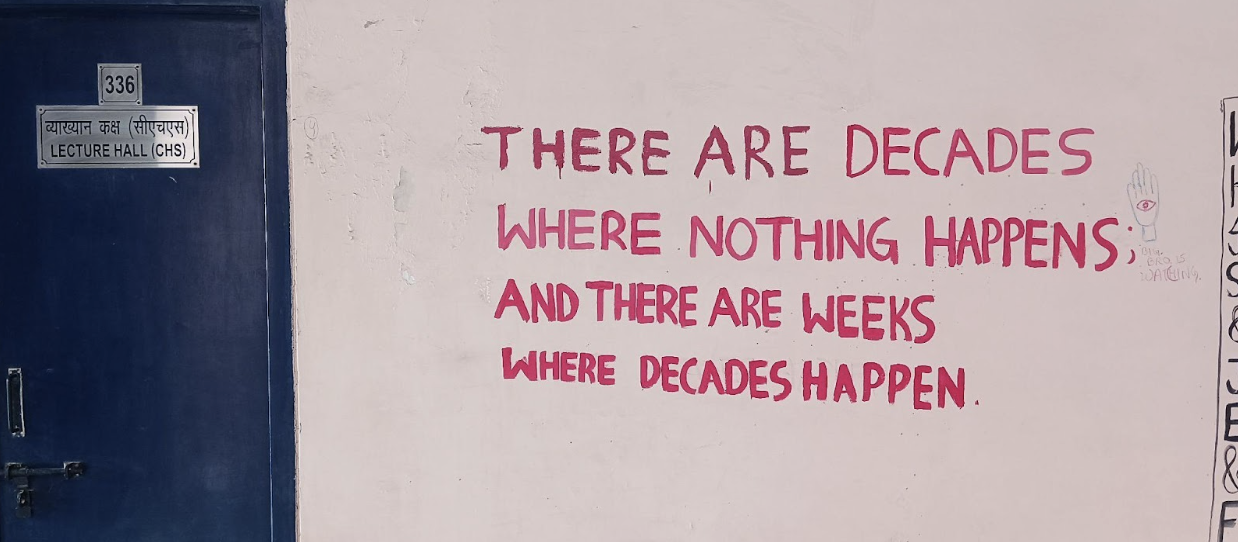

Graffiti on the ground floor of the Centre for Historical Studies, School of Social Sciences III Building at JNU. Photo: Author provided

The future of the Indian higher education system as envisioned in the New Education Policy, 2020, undeniably constructs further roadblocks to our ambitions. The vision(s) highlighted in the policy for the academic discipline of ‘historical studies’ is extremely narrow at best, and heavily prejudiced (on the grounds of ‘ideological inclinations’) at worst.

Although there are lofty mentions of providing encouragement for research facilities, everything seems to be far removed from the ‘truth’. For instance, it is worth observing that one cannot visit NMML, or even the National Archives of India without an institutional affiliation. Consequentially, we had to resort to the usage of digital archives, which are not at all sufficient as far as the orientation of our academic fields of research is concerned.

More graffiti at the Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University. Photo: Author provided

The university administration has a reputation for excessive delays in the disbursement of scholarships and fellowships, but it is usually very swift in the termination of institutional affiliations (and their associated benefits) for students who complete their degrees. A primary component of PhD applications is the preparation of a research proposal. It is a matter of basic understanding for anyone engaged in the process of historical research that the use of primary sources, especially those preserved within the spaces of institutional archives, is very instrumental to the academic discipline.

However, as mentioned earlier, we could gain no access to the corridors of the institutional archives after the completion of our post-graduation in June 2021. Due to these uncertainties, it was quite difficult to conceive a well-thought and articulated research proposal.

Despite all the challenges we have faced, especially in the post-pandemic phase after the completion of our post-graduation in historical studies, we strive to produce good academic research – which is something we have always been genuinely interested in. We would like to introduce a more theoretical/practical dialogue in the consideration of educational phases like the ‘pre-PhD’ period, which seems to have a lacuna in academic research.

Krishna Kumar (@Krishn_naa) and Somnath Pati (@rebel_academic) are former postgraduate scholars of Modern Indian History from the Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

Featured image: Nehru Memorial Museum and Library. Credit: Wikimedia Commons