This is the first of a three-part series on mohalla clinics in Delhi based on a ground investigation by students of TISS, Guwahati, along with the Centre for Youth Culture Law & Environment (CYCLE).

Delhi, a city of never-ending chaos, is viewed as one of the most developed cities in India. It is a place millions have migrated to search for better opportunities. Over the years, the population of the city has continued to steadily climb. To accommodate more and more citizens, the city continues to expand its border, swallowing up rural lands in the process. In the period after Independence, in an effort to solve the issue of housing refugees and migrants, many villages within Delhi were urbanised. Thus came the idea of ‘urban villages’.

As part of fieldwork as students of TISS, with Centre for Youth Culture Law & Environment (CYCLE), a Delhi based not-for-profit, we visited some of the different villages – Naraina, Kakrola, Nilothi, Mungeshpur, Jhuljhuli, Nangal Thakran, Bajitpur, Dariyapur Kalan and Katewara – that make up parts of Delhi.

It was quite surprising to see how these villages have a unique peculiarity. Some were urbanised decades ago and some are merely declared urban on paper, but all are within the same city limits. The main objective of our visit was to better understand ground-level realities and to get an idea of the state of education, employment and healthcare.

I visited different villages and spoke to people about the condition there, with a primary focus on primary healthcare and schools. With such a high population, they need good facilities for all age groups. Everyone has their own medical needs – from newborns to senior citizens.

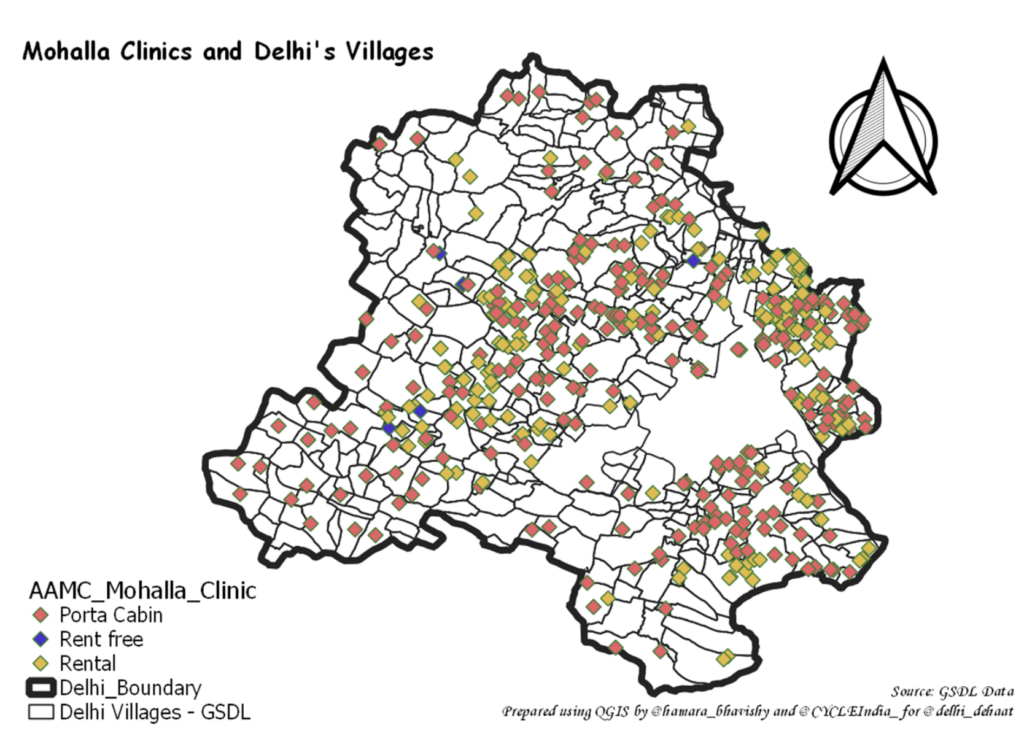

As for the mohalla clinics touted by the Aam Aadmi government in the city, none were to be found within a 3-4 km radius. According to the people we spoke to, even if there is a clinic near by, it is usually either closed or not well-equipped to handle many kinds of ailments.

When we asked them about how they managed moderate to extreme medical emergencies, we were told that they would head to hospitals some 12-14 kilometres away.

Note: This GIS based map shows how villages have no mohalla clinics and how a majority of clinics are rental and porta cabins, while the villages have vacant land that has potential to build hospitals with a capacity of hundreds of beds. The village we visited included Naraina, Kakrola, Nilothi, Mungeshpur, Jhuljhuli, Nangal Thakran, Bajitpur, Dariyapur Kalan and Katewara.

During the interactions, many women spoke about the lack of essential medical services related to their menstrual and reproductive health. It was eye-opening to see how the government plans schemes on paper and mindlessly implements them without understanding the people they are serving.

For a city resident, it is convenient to find healthcare. But in villages that are away from such necessities, absence of can mean the difference between life and death.

More so, the staff at these clinics are underpaid and exploited. Many are paid per-patient and are not given proper workplace rights. There are also enough loopholes in place to make money in the name of bogus entries. The whole mohalla clinic system starts to look hollow the closer one looks.

After looking at the information about these clinics in terms of numbers and the kind of facilities available, the much touted ‘Delhi Model’ sounds like mere rhetoric.

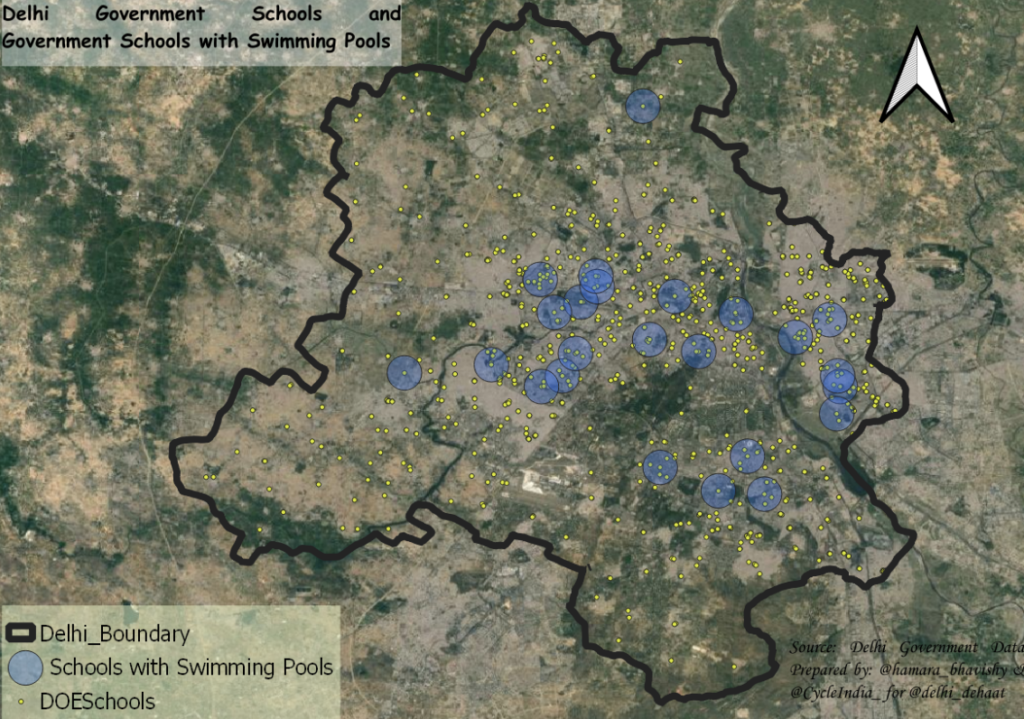

This GIS based map shows how inequitably the schools of Delhi government have sports facilities.

As citizens, we pay taxes and trust the government that they will work in favour of us and our future generations. One can only hope that the government we choose will understand our issues and resolve them.

Sajati Bhadouria is a MASW Counselling, 2nd year student from TISS, Guwahati.

Featured image: A worker sprays disinfectants on a closed mohalla clinic in IP extension, New Delhi, March 26, 2020. Photo: PTI/Ravi Choudhary