Patriarchy – glittering and so neatly presented on a plate – was not at all what I expected from the Barbie movie. I am conflicted if it was patriarchy oversimplified or just the perfect introduction to feminism for young women.

The 2.42-minute long trailer which came out roughly a month ago stirred something in me.

My friends and I were beyond excited and were asking our parents for permission to watch the film, every other day. We had absolutely no idea what the plot would be like but we knew for a fact that it would be iconic.

It didn’t fail to deliver on that.

Not a fan, but felt the pull

I was never a fan of dolls growing up. In fact, I was what you might call a boring child with other unconventional tastes. Yet, call it the power of dolls, the idea of such a film felt nostalgic to me and I wanted for the magic to guide me.

To see people of all ages, mostly dressed in pink, instilled an urge in me to join the cult.

My co-Barbies and I were dressed in pink and were channelling our inner child at the theatre. We ran around the mall to hug and compliment each other, further ‘disgracing the teenage name’. Side eyes were our companions. Ah, the beauty of female friendships.

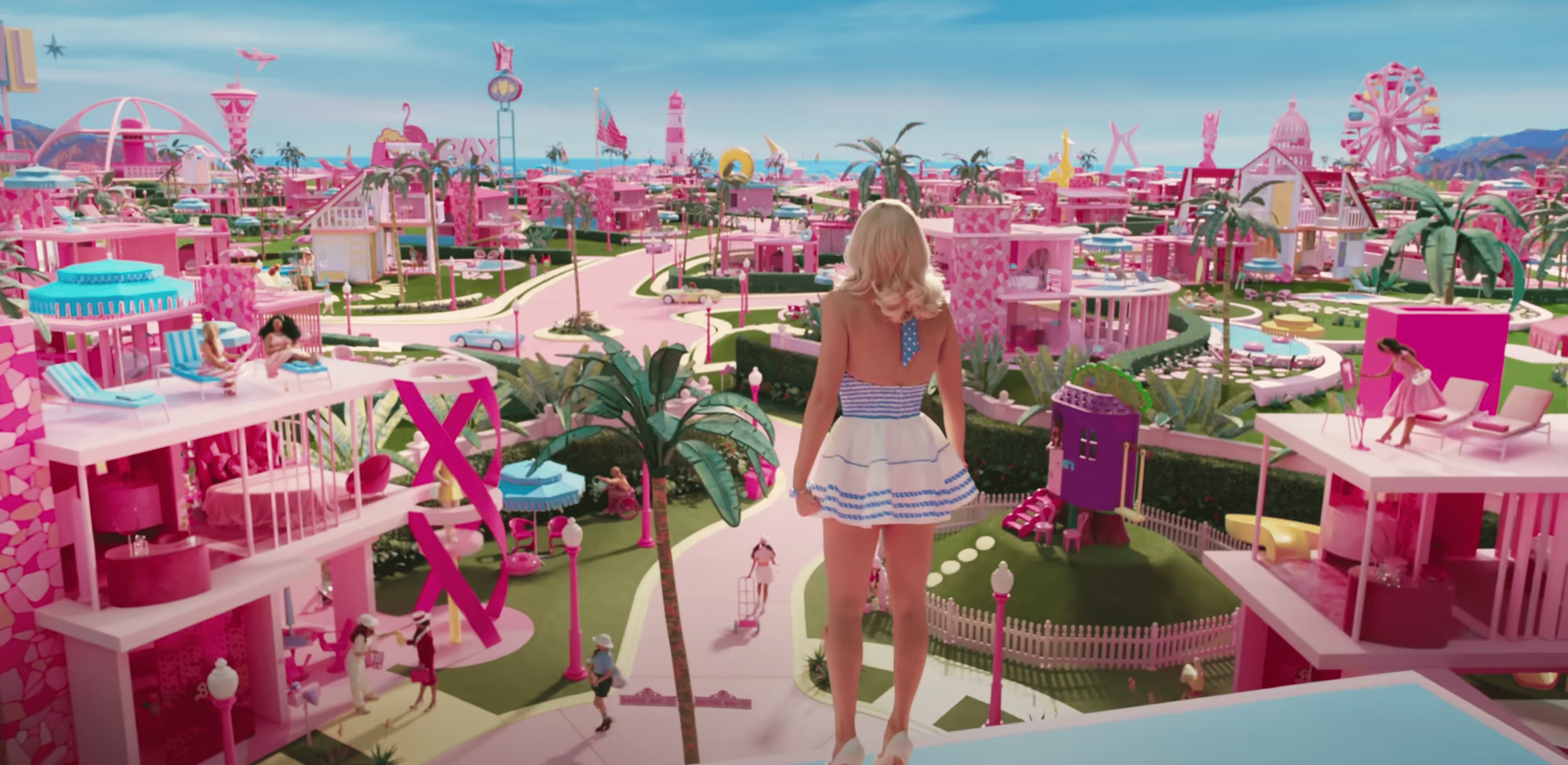

Paint a picture of what you expect from Barbie, it was exactly that.

All glitter and ‘perfection’, with the creepiness of doll-like behaviours by real, live ‘humans’.

But then…

Two contradictory things started happening, the perfect Barbie started malfunctioning. She went into the real world with the intention of fixing her disrupted ‘perfect’ life. Her protest against change left her lips multiple times. This felt insignificant compared to what her plastic heart had to deal with later on in the film.

The whole idea behind Barbie dolls itself is beyond significant today. In an age of body positivity and acceptance of unique beauty – which somehow goes hand in hand with toxic masculinity and embracing of misogyny – a female doll that can be everything she wants to be, but with caveats. The poster of the movie makes a play on this when it says, ‘She’s everything, he’s just Ken’.

One of the ‘Barbie’ posters.

Then there was Ken

Plastic Ken had no occupation, no identity of his own, not even a dream house. He was an accessory, an addition to Barbie’s life. As the narrator of the film says, ‘His day went well if only she glanced at him.’

Little Ken however changed miserably when he went into the ‘Real World’. The real world was the opposite of ‘Barbieland’. He was given respect there and quickly found out about patriarchy. He also developed an obsession with horses.

For example, the scene where Ryan Gosling (as Ken) goes into a hospital and asks for a doctor while talking to a female one is excellent. Ken had found out about the ‘superiority’ of his gender only a few hours ago, and even then he was so utterly entitled and confident that it really helped show how sharply patriarchy leeches onto one.

It was impressive how the notion of patriarchy was so easily and effortlessly accepted and learnt by the Kens. The Kens were unsure of themselves, wanted superiority to be served to them and wanted merely being ‘born a man’ to become their greatest superpower.

Ken, in a still from the film ‘Barbie’.

We as a society have been there, done that.

Barbie accepts defeat and goes into an existential crisis. The scene where Gloria (America Ferrera) is explaining the double standards set for women and just how ‘impossible it is to be one’, is powerful. It snaps Barbie out of her trance.

It felt exhilarating to watch this sequence, as these things have made their way into our subconscious. That they were finally articulated and made explicit was good to see.

As a 16-year-old girl, I am well aware of these pressures and double-standards.

Beyond pink

I adored how the Kens did not automatically have an equal place, but were made to gradually get there. In some sadistic sense, it gave me satisfaction. Barbie not ending up with Ken hurt my 10-year-old heart but this was such a refreshingly powerful move.

Ken figuring out he was enough (kenough!) and Barbie didn’t make him worthy – so he was better off on his own – and Barbie breaking from the shackles of her given identity of being the ‘stereotypical Barbie’ were all really powerful parts of the film.

The film had great potential. A movie this big, with superstars, could have been as effective as a school workshop. It truly did make an impact. But for me, the important question is whether that impact was like a footprint in the snow or like doodles on stone.

It did something, yet not enough – the spoon taken away after just a sniff. It felt almost ridiculous, how fast everything happened and how a concept (patriarchy) which is a major component of our societal fabric was resolved so easily.

A still from ‘Barbie’.

It left me uneasy because the fight against patriarchy has been going on for decades, yet to this day it rears its head high and comes armed with sharp claws.

The pink would have glittered, if towards the end, the men truly did realise their wrongs and accepted the importance of gender equality.

The term feminism has lately become a synonym for ‘hating men’ and claims the superiority of women over men, for some. The film could have used this opportunity and the attention that it commanded to showcase its true meaning.

In a world bleeding with misogyny, the film was a bandaid for teens and tweens.

Irene finds life in books, cats and music. She has adapted multiple personalities from characters, some thorns, some roses.