A Queen movie in India feels like such a significant thing. The band was so deeply important to so many people who grew up in the 80s, and generations after that inherited that love – and that music – in different ways. CDs in your parents’ car, old hit songs you just knew by heart without knowing how you knew them; the vision, the spectre of Freddie Mercury.

Bohemian Rhapsody does service to those memories – it plays like a jukebox movie, like the Mamma Mia films, an excuse for narrative build-up until the big hits. It also builds on the existing memory of the band in interesting, if not entirely satisfying, ways, and is an immersive and memorable watch.

The story embedded within Bohemian Rhapsody is one of accepting your roots and identity. The film begins Freddie Mercury’s journey by showing him watching musical acts at bars and pubs at night, rebelling against his parents, particularly his father. His father encourages good thoughts, good deeds, to which Mercury responds, “Where did that get you?”

He is also unequivocally uninterested in his Parsi heritage, being confronted with it at odd times in public and therefore denying it at home. When he performs with future Queen bandmates for the first time, one of them introduces him as “Fred Bul… sara.” The crowd is amused and confused and unwilling to listen to this name (they also yell out the slur, “who’s the Paki?”). All of that changes once he sings, of course; his mastery over the music and his initially flamboyant but then enrapturing stage presence means his name doesn’t matter at all. And that’s what he wants.

When his bandmates and girlfriend Mary visit his home, his mother (Meneka Das) brings out photo albums: Freddie looks at the camera in black-and-white, dressed as a boxer. Mercury is quick to deflect attention from these albums, from stories of why his parents left India for Zanzibar and then moved to England because they had to. He announces his name: Freddie Mercury. The camera here makes sure to linger on a shot of his father (Ace Bhatti), who looks, disappointed, at the photo of the boxer. “You can’t get anywhere,” his father says, “by denying who you are.”

The film, despite its directorial problems off-screen – Brian Singer was replaced, toward the end, by Dexter Fletcher – and its obvious partiality, given band members Brian May and Roger Taylor’s creative involvement in the film, still tells a good story. It tracks the newly baptised Freddie Mercury and his journey with Queen – their runaway success, their tour in the US, Mercury’s developing relationships with men and his alienation from Mary, the creation of Bohemian Rhapsody. It is during this creation that Mercury seems to own himself, in parallel with owning his roots. Studio executive Roy Foster (Mike Myers) is dismissing Bohemian Rhapsody, asking what all those funny words are – Galileo, Scaramouche… Ishmillah? –Mercury, looking ponderingly out of the window, replies only to the last one. “Bismillah.” He is literally uttering South Asia where he had not before.

After the success of Bohemian Rhapsody and its album, A Night at the Opera, Mercury changes, shifts. Things with Mary are tenuous; he is having more one-night stands with men, he is beginning a relationship with one of Queen’s managers Paul Prenter, which will then alienate him from his bandmates and launch him on a solo career. He grows increasingly more insufferable, and also more alone. When he finally fires Prenter, he utters that word again: “Home.” This is in marked contrast with how Prenter sees him: Mercury was always that frightened Paki boy, he says, illustrating exactly how little he understands.

The film is bookended by Queen’s iconic 1985 Live Aid performance. Mercury cuts off toxic influences, returns to his bandmates, and signs up Queen for this massive charity concert. It is when he comes back home to announce this to his father that he says the very words that first he dismissed: “Good thoughts, good words, good deeds.”

The film takes specific liberties with how it tweaks real events. Mercury’s HIV diagnosis, in particular, is revealed earlier on than he chose to reveal it in his real life. His bandmates are aware of it before the performance. The way the relationship with Mary is different from Mercury’s relationship with men is also a curious choice; his most lasting connection, on and off screen, was with Mary, but there is something slightly false in how Rami Malek and Lucy Boynton play these parts.

The music saves them again, though, and the music is inarguably the highlight of the film. It serves a dual purpose: as a ‘Greatest Hits’ playlist that will rekindle old memories for some, and bring the music alive for new, slightly unfamiliar listeners. A scene with Malek and Boynton in particular, that is set against ‘Love of My Life’, is beautiful and makes great use of a song that will become a classic all over again. The creation of ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’; the use of ‘Somebody to Love’; even ‘I’m in Love with my Car’. All of these songs come to life and the best parts of the movie are seeing the lyrics, karaoke style, loom larger than life.

Shreya Ramachandran is a writer based in Mumbai.

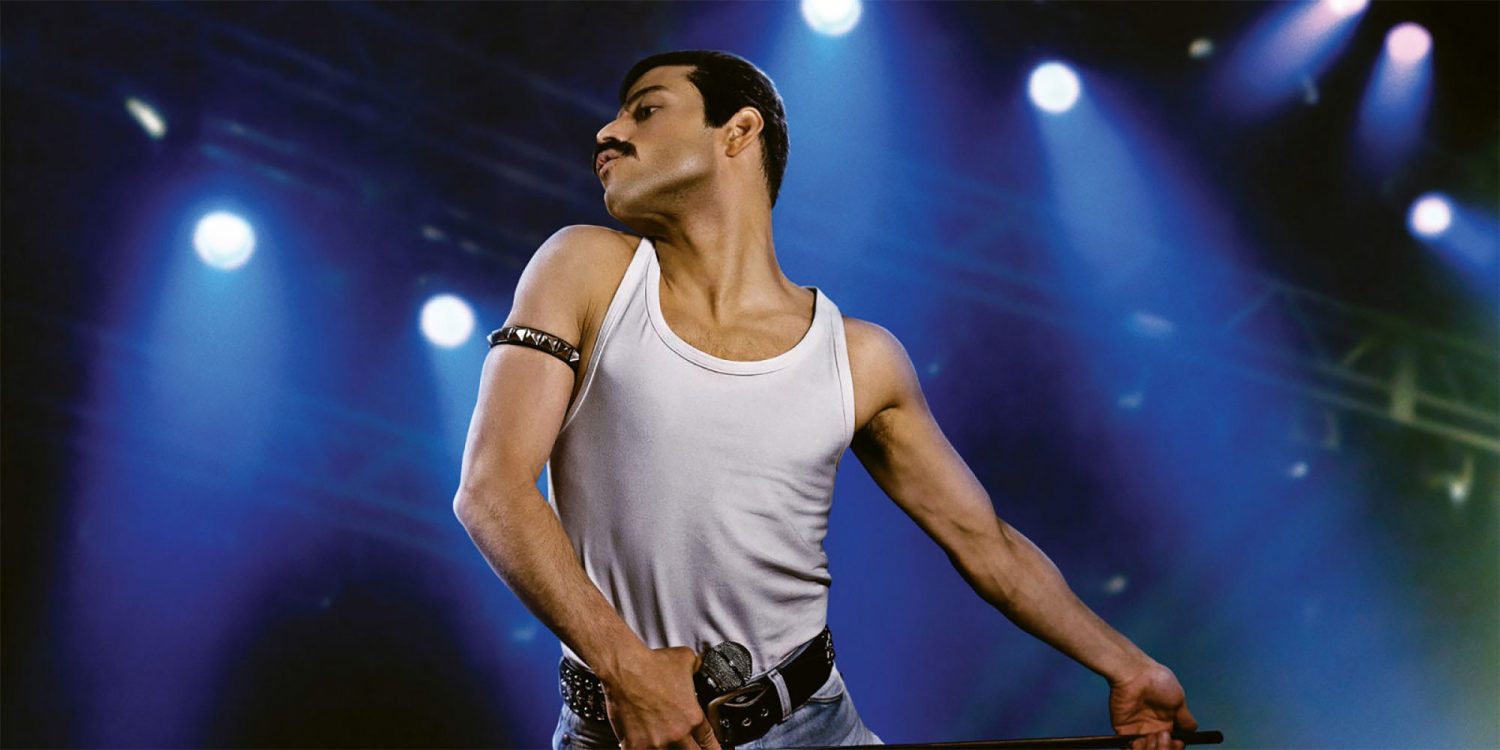

Featured image credit: 20th Century Fox