June 15 marked the 47th anniversary of the repressive state of Emergency in India which lasted for 21 months. The onslaught on civil liberties rendered citizens and the media docile. Former Attorney General Soli Sorabjee was among the lawyers at the forefront of assailing the government’s actions before courts.

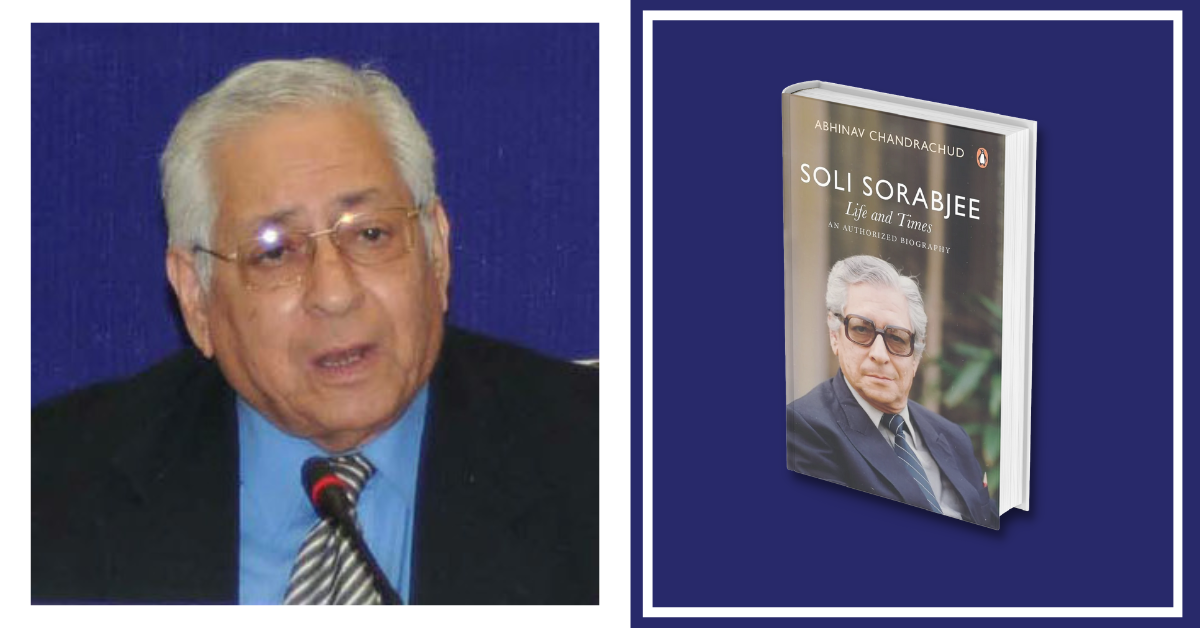

He was also an outspoken critic of the Emergency. Abhinav Chandrachud, Sorabjee’s authorised biographer, explores his illustrious life in the book, Soli Sorabjee: Life and Times. As the name suggests, it is not a conventional biography as Chandrachud gives readers an insight into the key political and legal events that shaped Sorabjee’s life.

It is a non-hagiographic account of the life and times of Sorabjee as the allegations and accusations against him have not been concealed. Interestingly, the description of his legal career is complemented with statistical data on appearances, wins, losses, etc. At a time when we are reminded of the horrors of the Emergency, while also being informed of officials unleashing the brute power of the State, events from Sorabjee’s legal career may provide an apposite perspective.

Sorabjee and the Emergency

Chandrachud writes that the Emergency catapulted Sorabjee into the national arena, as until then his focus was on cases pertaining to customs and excise law. During the Emergency, he represented political prisoners and media houses that bore the brunt of the government’s wrath.

As the operation of freedom of speech had been suspended, censors ran amok and muzzled criticism of the government. Minocher Masani, the editor of a journal called Freedom First was determined to challenge the censor’s prohibition on publishing 11 articles which were critical of the government.

Also read: Book Review: Through 50 Names, Rasheed Kidwai Reminds Us of India’s Pre-2014 Political History

Sorabjee represented Masani before the Bombay High Court, without charging him. He argued that the censor’s order was irrational and arbitrary as the articles were not prejudicial to internal security. He pointed out that the suspension of constitutional freedoms did not empower a censor to overstep his mandate of regulating only those articles that could truly endanger security. Thus, by drawing attention to the scope of the censor’s jurisdiction, Sorabjee convinced the court that free speech may not be regulated in an arbitrary manner, even during the Emergency.

Not only did the court rule that the rule of law ought to prevail during the Emergency but also went on to observe:

“Dissent from the opinions and views held by the majority and criticism and disapproval of measures initiated by a party in power make for a healthy political climate, and it is not for the censor to inject into this the lifelessness of forced conformity”.

Unfortunately, in April 1976, the Supreme Court dealt a death blow to liberty when it ruled that detainees could not challenge arbitrary detention orders before the courts as even the right to personal liberty ceased to exist during the Emergency. Though nine high courts had held that mala fide and illegal detention orders could be assailed, the Supreme Court failed to protect citizens from tyranny.

Sorabjee’s argument that the rule of law could not be subverted even during the Emergency and that officials were required to exercise powers strictly within the confines of the law, failed to impress the majority of the bench. He later wrote that the judgment was ‘disastrous’ and had ‘shaken the faith of the common man in the independence of the judiciary’. To voice his dissent during the Emergency, Sorabjee wrote a book on press censorship. Among other things, the book contained judgments of high courts striking down censorship, which had gone unreported by newspapers.

Tamas and Bandit Queen

In 1988, filmmaker Gopal Nihalani’s TV serial Tamas ran into trouble for its portrayal of communal violence during the Partition. There were violent protests and a petition was filed in the Bombay high court seeking a ban on the serial.

When the matter was taken up by the Supreme Court, Sorabjee appeared for Nihalani. He argued that a TV serial should not be judged from a fanatic’s standard. He went on to submit that if ‘beauty lay in the eyes of the beholder, then smut lay in the eyes of those inclined to view things in a distorted manner’. Eventually, the court ruled that the serial should be judged from a reasonable and strong-minded person’s point of view and not from that of a fanatic or a person with a vacillating mind.

Also read: Gogu Shyamala’s New Book Brings to Life Stories from Margins, Explores Caste, Exploitation

Sorabjee also represented the distributor of the film Bandit Queen – a film based on Phoolan Devi’s life. The Delhi high court had stayed its screening as some of the scenes depicted nudity. He argued that nudity could not be equated with obscenity in all cases. He explained that the objective of showing the protagonist naked was not to appeal to the viewers’ lust but to arouse sympathy for a victim of sexual harassment and generate anger at the heinous act.

Convinced by the arguments, the Supreme Court held that the purpose of censorship was not to “protect the pervert or assuage the susceptibilities of the over-sensitive” and ruled in favour of the filmmaker.

Sorabjee had a role in several landmark cases that resulted in the Supreme Court curbing the seemingly unbridled powers of the State and its functionaries. As the Attorney General, he opposed the Supreme Court’s decision to drop criminal charges against Union Carbide in relation to the Bhopal Gas Tragedy as it could lead to a ‘deep sense of injustice among the victims’.

Sitting judges and the government’s law officers would do well to pay attention to the following statement, when they are called upon to handle cases that involve the State using its might to bully citizens or coerce uniformity in public opinion:

“There is a certain core component without which a government cannot really be said to be based on rule of law — respect for basic human rights and dignity…A state in a free democratic society cannot have recourse to measures that violate the very essence of rule of law”

Rahul Machaiah holds an LLM in Law and Development from Azim Premji University.

Featured image (editing): Ujjaini Dutta