In 2019 at the Abantu Book Festival in Soweto, South African writer and artist Zakes Mda was celebrating the publication of his final novel, The Zulus of New York, when he made a surprise announcement. He had changed his mind and was writing another novel. He explained that “sometimes when you are a writer a story finds you and attacks you. It forces you to narrate it.”

The story is set in Lesotho, a landlocked and mountainous country neighbouring South Africa. It covers the growth of a kheleke – a wandering minstrel – and his career and the heights it is possible to reach, before tragedy engulfs and silences his accordion.

In Wayfarers’ Hymns, the author draws on his early life in Lesotho, where he joined his father in exile, and where he later taught at the national university. This novel re-connects the author to the land and culture of colourful blankets, Famo musicians and feuding factions, or “musical gangsters” as academic Nokuthula Mazibuko-Msimang calls them in a recent interview with Mda.

Subverting traditions

The central character is a nameless boy-child kheleke – “the eloquent one” – who sings the praises of his sister Moliehi. Despite the abundance of compliments sung by her brother, she describes him as a lazy leloabe (vagabond) and molelere (wanderer), with the connotations of a wastrel. But as the kheleke narrates the novel, it is his viewpoint that wins over. He explains in the first line that “she was the one I sang my hymns to” and he makes her name and beauty famous.

The tradition is explained thus:

A great hymn begins with the kheleke introducing himself to the world, repeating his name and his father’s, against his father’s if his father was a reprobate as men tend to be, and praising the virtues of his clan, his village and his chief.

And throughout Mda plays with this convention as the kheleke himself remains nameless, it is his “cult” (band) “of the arum-lily”, Mohalalitoe, that becomes famous. And although the kheleke sings about his father, it is a father who is missing, having died in a deep goldmine. He could not be buried among his kin in ancestral land and his spirit remains unappeased. In many ways it is the search for his father’s body that propels the action in the novel.

This apparently patriarchal form of music also praises the land, “even when the hymn is a lamentation. Even when the land is barren.” Before moving on to the sister: “A kheleke dwells on his sister and her unsurpassed qualities of womanhood.” Again the irony here is that the kheleke must sing about a “formidable woman in his life”, if he doesn’t have a sister, then his rakhali (paternal aunt) is the best he can do.

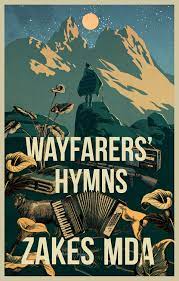

Wayfarers’ Hymns

Zakes Mda

Penguin Random House South Africa

Most importantly, “No self-respecting kheleke sings the praises of his wife in public, lest he invites vultures to his homestead.” And yet the song the kheleke becomes famous for U Ka Se Nqete celebrates female polyamory, or at least the ability of women to take different sexual partners while their husbands are working in the gold mines of Johannesburg.

This song that celebrates cuckoldry becomes an unexpected hit. The duet that the kheleke creates with his girlfriend, the dancer Maleshoane, is what cements the success of the song. It’s upbeat and funny, and though the men claim to dislike it, they all sing along.

Musical gangsters

In the ensuing battle between rival bands, the kheleke’s Cult of the Arum Lily directly challenge The Cult of the Train, an antagonism that leads to his downfall. Unknown to him, the cults also operate illegal mining operations and, as his father’s age-mate Tau ea Khale explains, things have changed greatly since the days when “warriors were warriors and musicians were musicians”.

The gangs arose in 1999, escalating in 2007, when Tau ea Khale describes being in prison and hearing of “inmates sentenced to years because they killed others over music … Mosotho killing another Mosotho for a song … boys who used to look after cattle together.” It is this snapshot of Lesotho gang warfare that Mda expertly captures in this novel, though it also celebrates music, composition and creativity itself.

Meditation on masculinity and femininity

Mda develops a significant meditation on masculinity as Wayfarers’ Hymns continues the pattern of Siphiwo Mahala’s When A Man Cries, Thando Mgqolozana’s A Man Who is Not a Man, and Masande Ntshanga’s The Reactive, all of which consider ulwaluko (traditional circumcision ritual) and what it means to be a man in southern Africa (during the HIV/AIDS pandemic).

A continued refrain amongst the men of his band is that the kheleke is disloyal because he is not circumcised and must “graduate from an initiation school” to be a man. He responds: “All I wanted was to be a kheleke of note, playing beautiful music, appearing on television … Radio.” But he is pushed by an attack on his sister to write a song which directly challenges The Cult of the Train and therein lies his downfall.

Mda develops different notions of freedom – in performance, singing, music and mourning – by bringing back the much-loved character of Toloki from his celebrated 1995 novel Ways of Dying. Toloki seeks more ways of mourning, away from the township and the HIV/AIDS bereavements of South Africa, with the deaths of the Famo musicians in Lesotho. Although he is a background figure in Wayfarers’ Hymns, Toloki provides ample comic respite from the posturing and machismo of the gang warfare. He also challenges us to rethink categories, bringing his performance of ‘grief’ to Lesotho and then juxtaposing it with his own genuine grief at losing the love of his life.

Mda has always written strong female characters, but in Wayfarers’ Hymns he also classically undercuts notions of femininity by making Moliehi a woman who loves another woman, providing unexpected female khelekes and featuring female gangsters called MaRussia like Mme Mpuse. She offers her sage advice to the boy-child kheleke when he sings with her. She tells him, “One day you will be a sought-after kheleke. But never be led by your penis. That’s what has destroyed great men. Be led by the music.” The Wayfarers’ Hymns are songs worth listening to.

Lizzy Attree, Adjunct Professor, Richmond American International University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Featured image: Lesotho singer and rapper Teboho Mochaoa Morena Leraba seen in the fields outside the village of Ha Nchela. Photo: Reuters