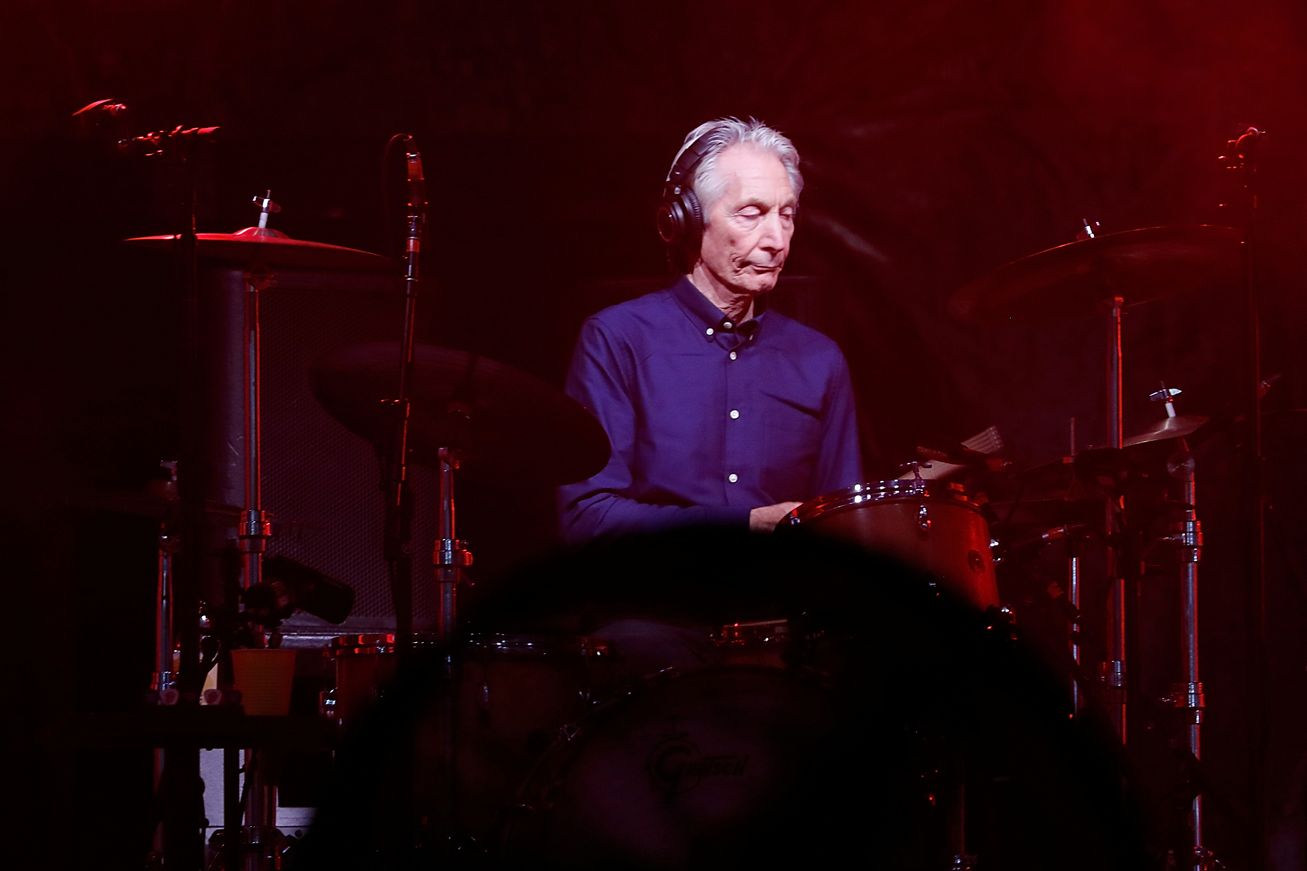

Drummer Charlie Watts, who passed away on Monday, was as integral to the Rolling Stones as its frontman Mick Jagger and songwriting partner and guitarist Keith Richards. As Watts’s biographer Mark Edison put it: “No one dances to the guitar solos. No one dances to the words.”

Watts’s drumming was unique. He differed from his peers in the rock drumming pantheon, partly due to being a jazz aficionado, a sensibility that he took to the music of the Stones, and also through his self-contained manner. For someone at the heart of a legendarily dissolute band, he largely eschewed both the glitz and grime of his milieu.

Watts wasn’t formally trained as a jazz drummer, but like fellow Rolling Stone Brian Jones and Cream members Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker, he passed through the early sixties British blues evangelist Alexis Korner’s outfit, Blues Incorporated. He idolised jazz pioneers including Max Roach, Tony Williams and Joe Morello, and his jazz sensibility – his capacity to “swing” – informed the Stones’ music.

A jazz sensibility in a rock format

While the Stones’ most obvious musical inspiration was the blues, Watts’ drumming had the fluid yet disciplined tendencies of jazz. Few would say he pulled the Stones in an overtly jazzy direction – this would be something he would explore more fully later through side-projects in the 90s, including a big-band and a jazz quintet. But his jazz underpinning would help the band incorporate other genres into their repertoire, from reggae to funk, which helped expand what a rock sound was.

One such sound was the Afro-Cuban mambo groove, which he became familiar with via big band music. This allowed him, as drumkit historian Matt Brennan points out, to play seamlessly alongside conga player Kwasi Dzidzornu on Sympathy for the Devil, which opened the landmark Beggars Banquet album when the Stones sought to broaden their palette in the late 60s.

While he was able to stretch out across genres, Watts’s playing was uncharacteristically unflashy for a drummer in a rock band. Brennan identifies a set of traits that, in the popular consciousness anyway, are associated with rock drummers – being primal, powerful, virtuosic and exhibitionist. On the face of it, Watts displayed none of these.

Unlike Led Zeppelin’s John Bonham, he was not an especially powerful hitter. He lacked the quixotic flair of The Who’s Keith Moon, and his playing was far removed from the complex virtuosity of the prog-rock and fusion players who emerged in the 1970s, or indeed, his jazz influences like Roach. Self-effacing as well as self-taught, for Watts, serving the song was key.

“I try to help them get what they want”, he said of Jagger and Richards. “I don’t think what I do is particularly difficult. What is good, though, is that people look at me and say, ‘Well, I can do that’”. But doing what he did is not as easy as he made it sound.

Modesty and distinctive simplicity

Watts’s hallmarks were simplicity and a feel that provided both space and a solid base for Keith Richards’ open-tuned swagger on guitar. The Stones groove derived from how Watts played infinitesimally behind the beat, which Richards has attributed to his distinctive style, and credited as foundational to the Stones sound.

On the hi-hat, most guys would play on all four beats, but on the two and the four, which is the backbeat, which is a very important thing in rock and roll, Charlie doesn’t play. It pulls the time back because he has to make a little extra effort.

And so part of the languid feel of Charlie’s drumming comes from this unnecessary motion every two beats. It’s very hard to do – to stop the beat going just for one beat and then come back in … And the way he stretches out the beat and what we do on top of that is a secret of the Stones sound.

The Stones, then, relied almost as much on what he didn’t play – on the space he left – as on what he did. Watts himself said, “there are a million kids who can play like me”. But it was his deceptively difficult and idiosyncratic playing that propelled hits such as Honky Tonk Women and Start Me Up.

In Honky Tonk Women, this can be heard in the slight mismatch between the cowbell and his drums. Then again in the way he subtly pushes the tempo as the song nears its conclusion, which makes it simultaneously a standard rock beat with a tinge of funkiness – without overt syncopation.

“No Charlie, no Stones”, Keith Richards has repeatedly stated. His passing will surely test that claim to its limits. Ultimately, he shaped rock and roll by ignoring its expectations. “Charlie’s good tonight, innee”, said Jagger on the live 1970 album Get Yer Ya Yas Out. This was both true, and beside the point.

Modest, understated and reliable in a musical world characterised by volume, extravagance and mercurial personalities, Charlie was always good on the night.![]()

Adam Behr, Senior Lecturer in Popular and Contemporary Music, Newcastle University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()