“Don’t question your elders. When you’re older, you’ll understand.”

This is a phrase most Indian children have heard and consequently imbibed. From a young age, many of us have been programmed to sit, listen, and nod our heads in agreement when faced with figures of authority.

India is considered to have a high power index (77), as defined by the psychologist Dr. Geert Hofstede. The index is used to measure to what degree does a society accept inequality between those in positions of power and those on the margins. India’s high power index indicates that we appreciate hierarchies and have a high level of respect for authority and those in leadership roles.

In such a culture, Indian students are already at a disadvantage when it comes to developing critical thinking and reasoning skills. For history students, like me, this creates a clear hindrance. Historians are meant to question the evidence and strive to produce an objective view of it, overcoming challenges of differentiating between fact and opinion. However, in such a hierarchical society, the lines between opinion and fact often gets blurred. This becomes particularly dangerous when unconstitutional ideas are propagated through different mediums.

Worryingly, in the last couple of years, religious affiliations now seem to play a critical role in the introduction of leaders into history textbooks. For example, according to an opinion piece by Christophe Jaffrelot and Pradyumna Jain, a Class 8 textbook in Rajasthan introduced in 2017 by the then BJP government referred to B.R. Ambedkar as a ‘Hindu social reformer’. The use of the word “Hindu” diminishes Ambedkar’s life-long struggle against the caste system and overlooks his later decision to convert to Buddhism.

Also read: School Textbooks Need to Teach the Constitution, Not Sing the Government’s Praises

The piece also talks about Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, a key ideologue of Hindutva ideology, being described as someone “…whose contribution to the cause of independence cannot be described in words,” in school textbooks. For a historian, this goes against the grain. The very point of a leader’s contribution is that it can be described, examined and validated – mistakes may well have been made on both sides of the political spectrum.

In 2015, ex-culture minister Mahesh Sharma said that modern history was presented in a manner that glorified members of the Nehru-Gandhi family and not other freedom fighters and leaders. However, in re-writing history, it seems that pieces of history have been selectively omitted to portray a distorted vision of India’s past. According to historian Mushirul Hasan in his paper, ‘Textbooks and Imagined History‘, writes, “Just as the arrival of postmodernist theory in the 1980s led to ‘an extended epistemological crisis’ in the West, India’s current intellectual climate and the ensuing historical controversies have thrown the historical profession into disarray.” He added that at the RSS Vidya Bharati schools, students are taught that Islam “teaches only atrocities”.

Currently, with all focus on the pandemic, the NCERT administration has hastily brushed up the syllabus. The most prominent change can be seen in the political science textbooks. For instance, they have removed critical chapters that form the basis of the Indian constitution such as citizenship, nationalism, and secularism from the curriculum for Class 11 in the academic year 2020-’21.

Amidst a pandemic, when we are all dealing with loss of all kinds, curriculum modifications like these often go unnoticed. However, these changes will leave a lasting impression on young minds who wouldn’t even have the ability to think critically or to find their own voice. They’d just be prototypes of the vision of a ‘New India’.

Yaamini Singh is a 17-year-old student at The Shriram School, Moulsari. She is an avid history buff.

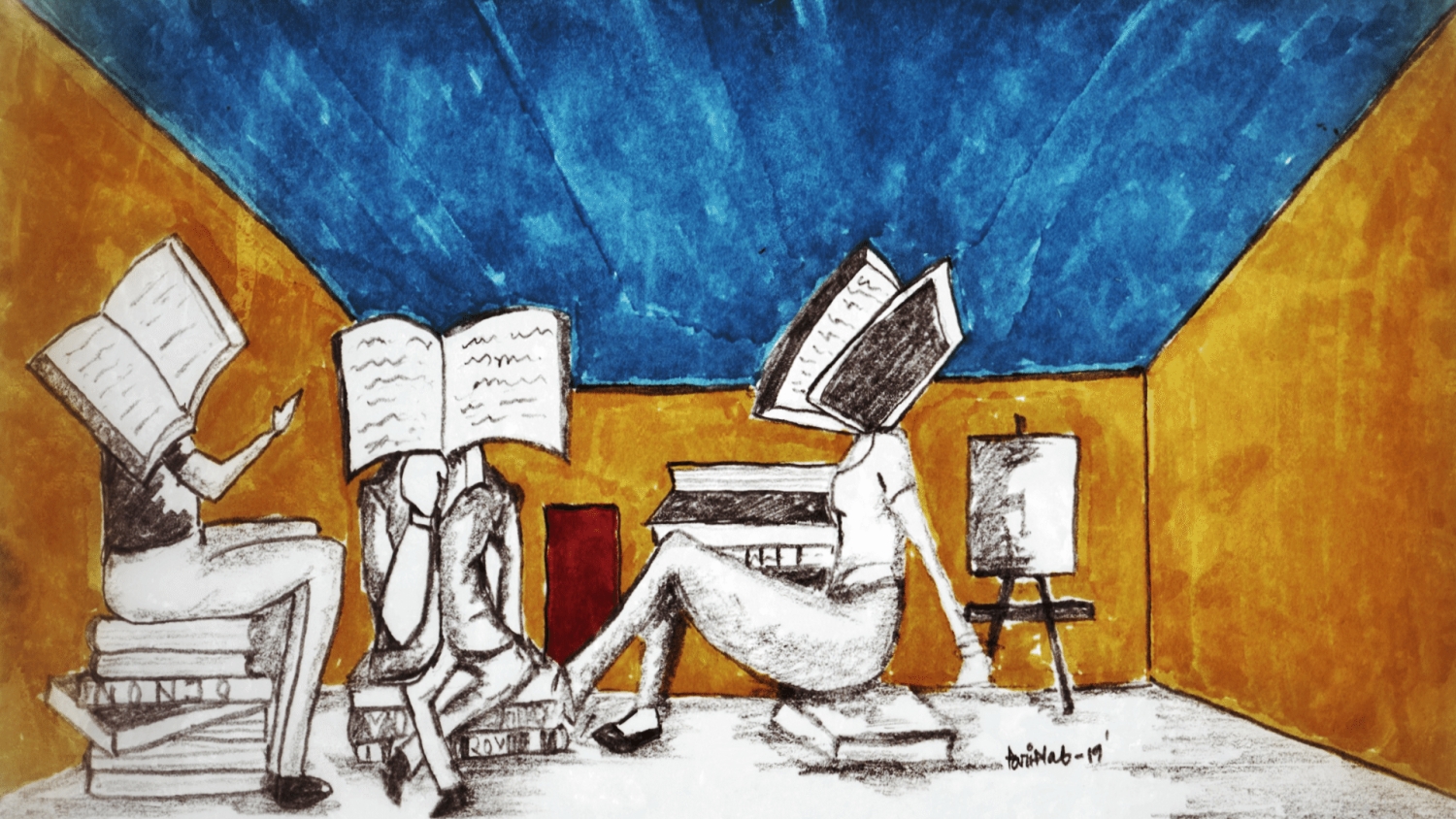

Featured image credit: Pariplab Chakraborty