“…I do not cross my Father’s ground to any House or town,” replied Emily Dickinson in a letter to Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson, the writer, abolitionist and soldier.

She had been invited three times by Higginson to Boston to attend his lectures and meet other poets to have literary discussions. Higginson was one of Dickinson’s regular correspondents, one with whom she shared her poems as well. Yet she rejected his invitations, even to meet other contemporary poets.

All women are dangerous, if we go by most traditional texts which have discussed women and especially those which have been written by men. But perhaps the lone woman is the most dangerous or, at least, the strangest of them all. The single adult woman with no husband, no children, and with no desire for a family, is suspect. Such a woman, who also shuns socialisation and enjoys solitude, should be distrusted and/or dissected, because she is supposedly an irregularity, a glitch in the normal order of things.

Emily Dickinson fulfilled all of these criteria.

Also read: Woes of a ‘Child-Free’ Indian Woman

During her youth, Dickinson had a social circle and a fiancé. But towards the latter part of her life, she gravitated more and more towards isolation. Although she disliked household chores, Dickinson now restricted herself to her home, engaging in baking, gardening, sewing and being devoted to her dog Carlo. The rest of the day, she spent in her room at her tiny writing desk beside the window, composing nearly 1,800 poems during her lifetime, and writing letters to close to 100 correspondents.

Writing letters and poems in her few spare hours was the only way she could hone her writing skills and socialise at the same time. For a 19th century woman, as for most modern women bogged down with household work, time for practising her art was preciously limited.

Thus, Dickinson’s crime was not only radical poetry. It was also her choice to be alone and socialise mostly through her letters. The reason for this preference can be found in her words, for Emily Dickinson was an outlaw. Like a true rebel, she placed great importance on freedom. She had an acute aversion to power and dogma. It is evident that she was well aware of the societal limitations on her and she frequently she tested this “circumference”.

Also read: A Diary of Loneliness

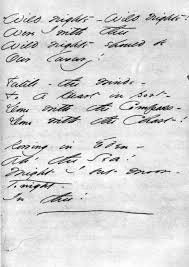

Dickinson must have realised that even if she did venture out of her home, this freedom was going to be superficial. There would always be places she would never see during her lifetime. So she visited these impossible sites through her imagination and in her poems. She experienced “wild, wild nights” and early one day she took her dog “and visited the sea”. Emily Dickinson never got to see the sea.

Emily Dickinson’s home at Amherst, Massachusetts. Photo: www.emilydickinsonmuseum.org

But the borders of time and space were not all that Dickinson blurred. She also knew that she would never be able to truly be herself among a crowd of people. So within the confines of her room, she negotiated the lines of her sexuality and gender, sometimes tiptoeing on them (as in her cryptic poems) and at other times, thumping upon them (as in her explicit letters to Susan Huntington Dickinson or “Susie”). Her room was the only space where there was no judgment. Only her words could truly give her freedom.

Emily Dickinson’s handwritten manuscript for “Wild Nights-Wild Nights!”. Photo: Emily Dickinson archive

But for this love of seclusion and yearning for free will, she was punished by her early publishers – who were instrumental in forming the image we have of Dickinson even today. It is thus that we have the idea of the detached, lonely, probably bitter poetess in white robes scribbling away on pieces of paper at a little desk.

It came to be assumed that she was forced into isolation after a possible heartbreak because this deliberate choice to be alone did not make sense for a woman.

Also read: Why Do Good Male Authors Write Bland Women Characters?

Pablo Picasso had said, “Without great solitude, no serious work is done.” Picasso too supposedly turned into a recluse late in his life. But while a brooding loner male figure is usually an object of attraction and fascination, his female counterpart might have been burnt at the stake during the Middle Ages and is branded an oddity even today.

Much scholarly work has gone into reinterpreting and understanding the personality of Emily Dickinson, yet the impression of the solitary and thus tortured poetess refuses to completely leave her. Even after the discovery of so many letters by Dickinson, indicating her range of correspondence, and her writings which indicate the freedom of her mind and spirit, the image of the pitiable hermit still stands strong.

Perhaps this is an indication of society’s fixation with the anomaly called “the lone woman”. This image might have been a marketing ploy to pique the interests of poetry enthusiasts. Nevertheless, it cannot be denied that it is neither a very desirable nor an accurate one.

One day, Dickinson’s niece Martha visited her in her bedroom. The poetess pretended to lock the door with an imaginary key and then turned to her niece and said, “Matty, here’s freedom.”

This idea of liberty and love for quiet and seclusion shared by Dickinson and many women is seemingly radical even in today’s world.

Deeplakshmi Saikia is PhD research scholar, Visual Studies and Art History, Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Featured image credit: Wikipedia