‘Mainstream feminism’ in India has hitherto had glass ceilings of its own kind. From history books being authored by upper-caste writers, to capitalist corporates constantly expanding on surname privileges, or the elite entertainment industry propagating dominant-caste standards of beauty – the contributions and sacrifices of pioneering Bahujan women have not only been obliviously sidelined, but they have also been intentionally abandoned.

Knowing about Fatima Sheikh, hence, becomes imperative in myriad aspects. The salient one being how she, along with her brother Usman Sheikh, had given their own residence to Jyotirao Phule and Savitribai Phule to establish the first school for girls in India in 1848. This decision was not only a deed of goodwill, but was in fact an action of colossal courage. Society back then considered female education a sin. This lead to Jyotiba Phule’s father to ask him and Savitribai Phule to leave the house when the two decided to champion the cause of female education and rights.

This act of establishing the school thus, is not just another fact about the Indian feminist history – this act is the history of feminism in India. It not only broke glass ceilings, but also paved way for an entire new universe of educated, assertive, independent Indian women. And while all four of them – be it Jyotiba Phule, Savitribai Phule, Fatima Sheikh and Usman Sheikh – faced heinous attacks, Fatima Sheikh, a Bahujan woman said to belong to a farming caste, faced resistance from all sides; be it from religious fundamentalists or from those upholding brahmanical patriarchy.

Also read: Caging Women Is Violence – Not ‘Safety’ or ‘Protection’

Undeterred, she studied teacher’s training along with Savitribai Phule and taught in their self-established school in Pune while also managing the affairs of the school. And unlike today’s elite schools which cater to the privileged caste-class in India, back then, parents were not queuing up for admission forms outside school gates. In fact, fearful of societal backlash, most parents were very reluctant to send their girls to school.

Fatima Sheikh then went from house to house to convince families to enrol their daughters. Even though upper-caste men and women threw mud and cow-dung at her and passed all sorts of abuse as she walked on the streets, Fatima Sheikh pursued her cause. Consequently, girls from all castes, religions and economic backgrounds who came from localities which barred them from intermingling or dining into each other’s homes owing to religious and casteist segregation, received education under the same roof.

In a society which constantly pits women from the privileged caste-class against each other even today, back then in the 19th century, Fatima Sheikh and Savitribai Phule (both Bahujan women) became the first female teachers of India and manifested what happens when two underprivileged, marginalised women join hands – that together they bring about a revolution. Maybe that is why dominant caste-gatekeepers don’t teach us about them in course-curriculums or make them a part of the mainstream media narrative, because they are afraid; afraid of history repeating itself, afraid of marginalised women challenging the status quo.

Also read: The Hollow ‘Wokeness’ of Educated Upper Class, Caste Women

This act of relegating Fatima Sheikh to the margins cannot be a mere coincidence. It is an erasure akin to diminishing history. This is not to say that such practices have been curbed with time. Even today, through active gaslighting, trivialising, as well as space-hogging, the career-building of ‘elite feminists’ happens on the trauma and dead bodies of Bahujan women. The same so-called upper-caste women – who rightfully write on the gender-based wage gap in the educated diaspora, and who face patriarchy propounded by dominant caste men in homes, universities and workplaces – themselves do not practice labour rights when it comes to the Bahujan women working as domestic help, construction workers or vegetable vendors. They refuse to understand the narratives of Bahujan women, the way white women discouraged black women.

No wonder then, that the poems of Savitribai Phule were not taught in most schools; that the life history of Fatima Sheikh was not discussed in most course books. The fact that Dr. Ambedkar fought for the Hindu Code Bill so that women got the right to property, divorce, remarriage and bodily autonomy, was mostly not a part of the common syllabus, and most history books didn’t actively spoke of how Jyotiba Phule and Periyar E.V. Ramasamy fought for women’s rights. Mainstream feminism in India has failed its own foundation by failing to remember Fatima Sheikh and her idea of inclusive education.

Learning about Fatima Sheikh then, teaches us that the phrase “pass the mic” comes from a place of policing where dominant-castes believe that the mic is theirs to give, when in fact, the stage itself has been built on the labour of the marginalised. It is therefore, sacrosanct to comprehend that having inter-sectionalism in feminism is not an option – it is the essence of feminism itself.

Ankita Apurva was born with a pen and a sickle.

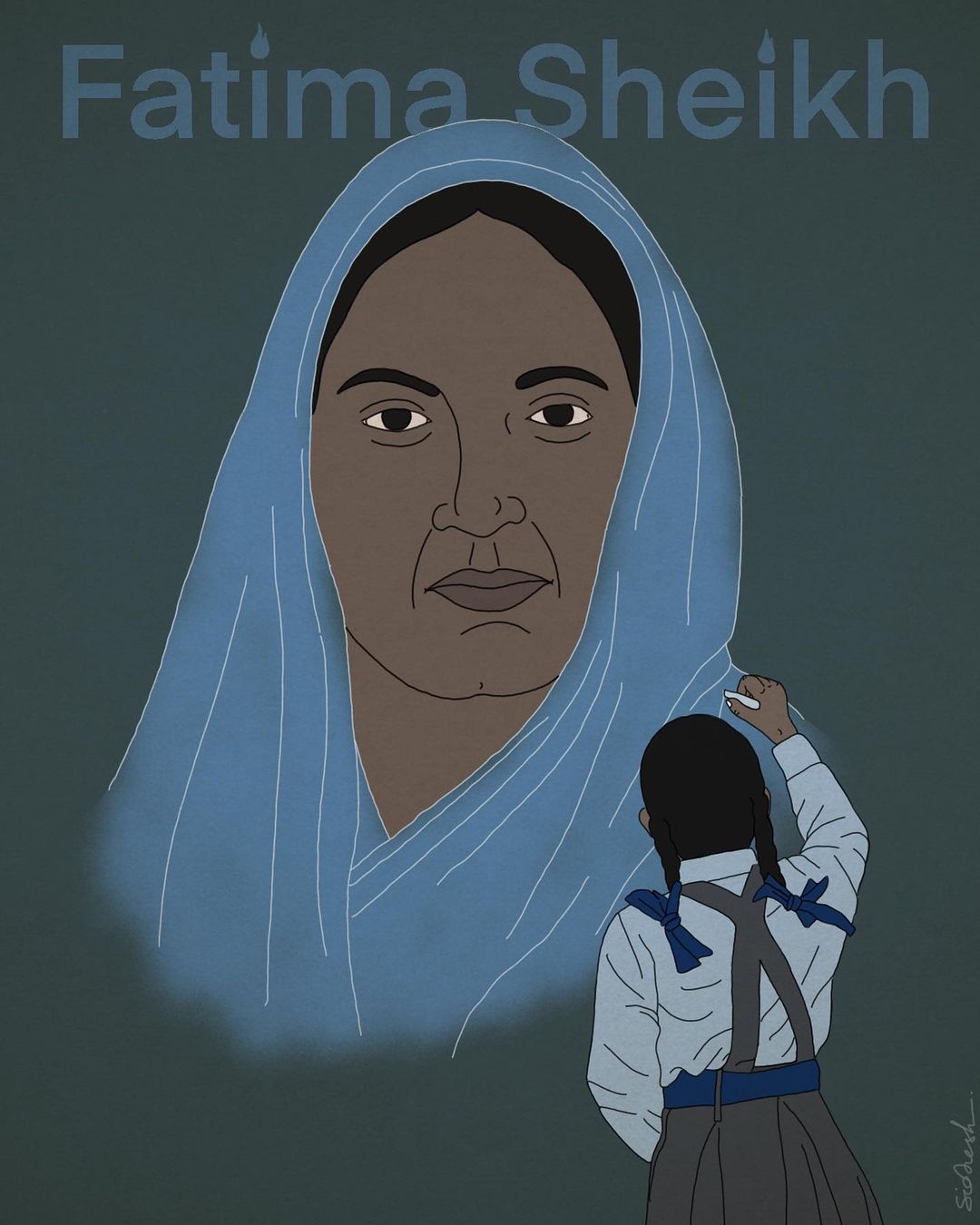

Featured image credit: Siddhesh Gautam/@bakeryprasad