Trigger warning: This article contains details about domestic abuse which may be triggering to survivors.

She is beautiful.

That is the first thing I notice. She wears designer clothes and travels in fancy cars. Today, it is a car I haven’t seen before. An SUV. Before that, it was some luxury car. And before that, I can’t remember.

She has friends, lots of them. She laughs a lot, and she talks a lot. Sometimes, she sings (mediocrely), to the ever-present stream of applause from the people around her.

“What does her father do?” someone asks, to my right.

“Some government job.” someone else replies. “Did you see her Instagram? She went to New Zealand for the holidays.”

I envy her. She will never know what it’s like to yearn for a life outside the four walls of an oppressive town. Never know what it’s like to worry about things like student debt, job prospects, a family’s future.

§

One day, we are partnered for an assignment. We have to write a children’s book together, due in a month’s time. I see her walking towards me, heels clicking on the floor lightly, and I resist the urge to roll my eyes.

“Hi, I’m really excited to be working with you,” she says, and I almost wish she’d said something ruder, something more commensurate with the Regina George persona I’d created for her in my head. It’s much harder to dislike someone when they’re nice to you.

“Same. Any ideas?”

“Actually, I was thinking we could write a story and turn it into an audiobook along with a physical copy.” Begrudgingly, I think it is a good idea. “I’d love to illustrate it, if that’s okay with you.”

“You draw?” I ask.

“Digital art.” Her long sleeves brush against my hand as she turns to pull out a large iPad from her bag, whatever the latest model is these days, and of course, she owns an iPad for her art. Her drawings are semi-realistic and gorgeously rendered. I mumble an inauthentic approximation of a compliment to her. Talents are for the privileged. When one is rich, it is a marker of a holistic and productive personality. When one is not, it is a waste of time and money. I feel the chasm widen between us.

§

I am the first one to return home from the holidays, later trains completely booked. Or so I think. Four days before classes resume, I see her in the bathrooms of our hostel applying ice to her shoulder.

“Do you need some help with that?” I ask.

She starts. “No, I’m fine, thank you.” She smiles at me.

“That looks like one hell of a bruise,” I tell her. It does look like one hell of a bruise. Black and angry.

“I fell,” she says simply.

“Oh, okay. I’m in room 406, let me know if you need anything.” I leave, feeling proud of myself. Later, I wonder if things might have gone differently if I’d stayed and questioned her a bit more.

§

I start noticing things. She rarely goes home during long weekends, much like me. But for me, it is a question of distance. I live 37 hours away, she lives one. She never goes out.

“Why?” I ask her, once.

“My parents have a tracker on my phone, I’m not supposed to leave.”

“Swap phones with me for a bit,” I tell her, madly. It is much easier to like someone when they are struggling. Humans, I think, have an innate sympathy-override.

She laughs. “Thank you, but it’s okay.”

§

“Borrow my dress,” I tell her. We are friends now, and I am convincing her to come with me to a party.

“I can’t, it’s too short.”

“Your parents aren’t here,” I remind.

“No, but if they find out they’ll…” she stops.

“They’re not here,” I say gently, “and you would look so beautiful in this dress.” She would. Sometimes I think she is one of the most beautiful people I have ever met.

“It is so easy for you to say, you are so thin and pretty. You will never know what it’s like to…” she breaks off, face red.

“To what?” I am alarmed. Does she really think…?

“To look like me,” she says, softly.

“When has anyone ever said that?” I ask.

“I have been told so for as long as I can remember. It must be true.” It must be true.

§

“Happy birthday,” I tell her. We are best friends now, and I think I am in love with her a little bit. I hand her a small cupcake with an unlit candle. “Make a wish.”

She does. “I wish that this year, my parents will speak to me on my birthday.”

My heart clenches. “You’re not supposed to tell me your wish, then it won’t come true.”

“We are best friends,” she says, “there are no secrets between us.”

§

Do I still envy her? Of course I do. She will never know what it’s like to yearn for a life outside the four walls of an oppressive town. Never know what it’s like to worry about things like student debt, job prospects and a family’s future.

But it is not so simple anymore.

I will never know what it’s like to yearn for a life outside the four walls of an oppressive home. Never know what it’s like to worry about things like raised voices, hiding bruises and a family’s past.

She is everything I thought her to be, and she is not. She wears designer clothes and drives fancy cars. She sings (mediocrely) and draws (extraordinarily). She uses receipts as bookmarks, religiously avoids caffeine, wears long sleeves and lies about bruises. She teaches me, everyday, that people are complex, vulnerable and resilient.

“Wear the dress,” I tell her, after we graduate. “You are the most brave, beautiful, kind, intelligent person I have ever known, and anyone who has ever told you otherwise is wrong.

“Okay,” she says, unbelieving, but it does not matter. One day, I will make her believe.

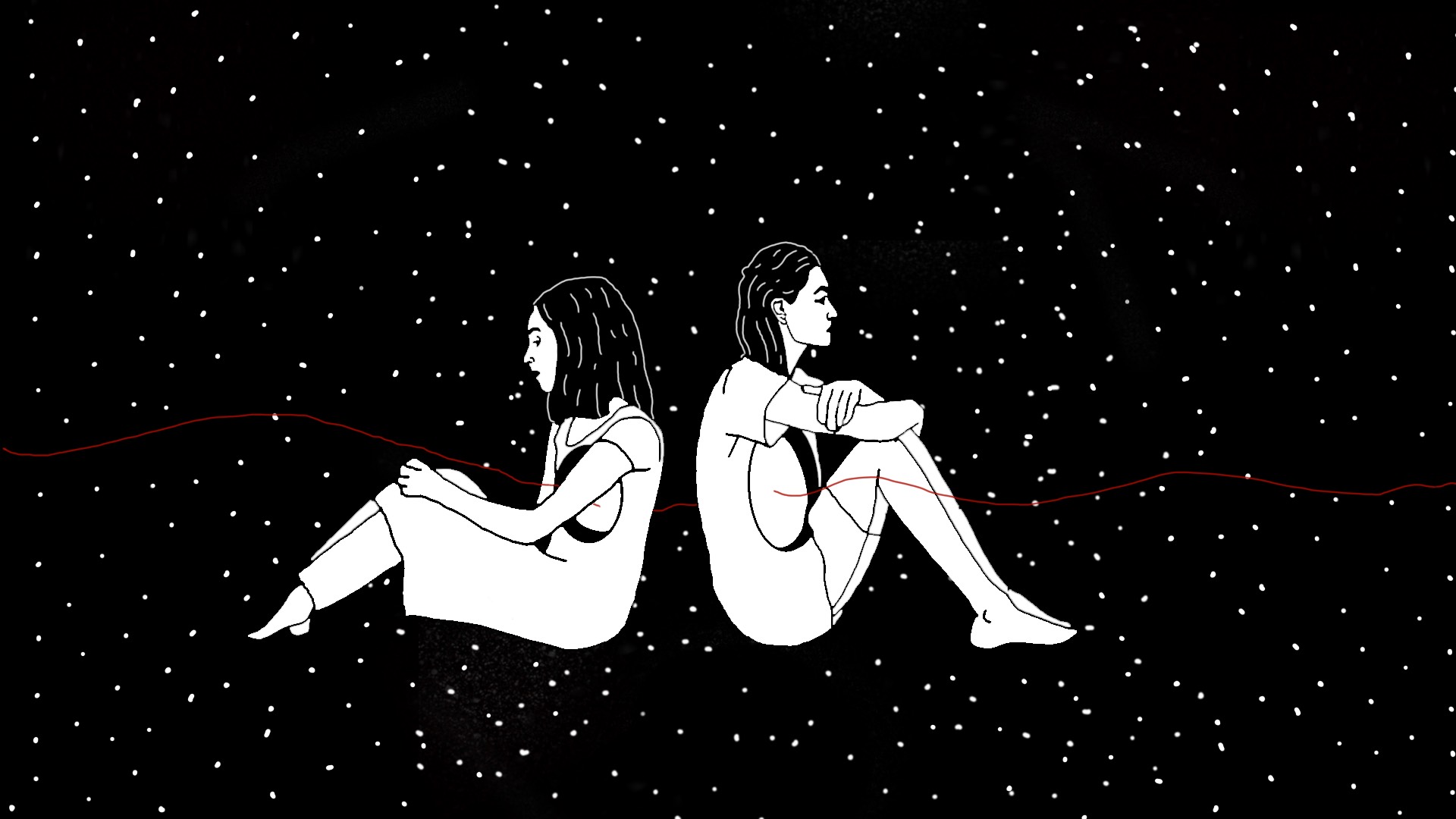

Featured image credit: Pariplab Chakraborty