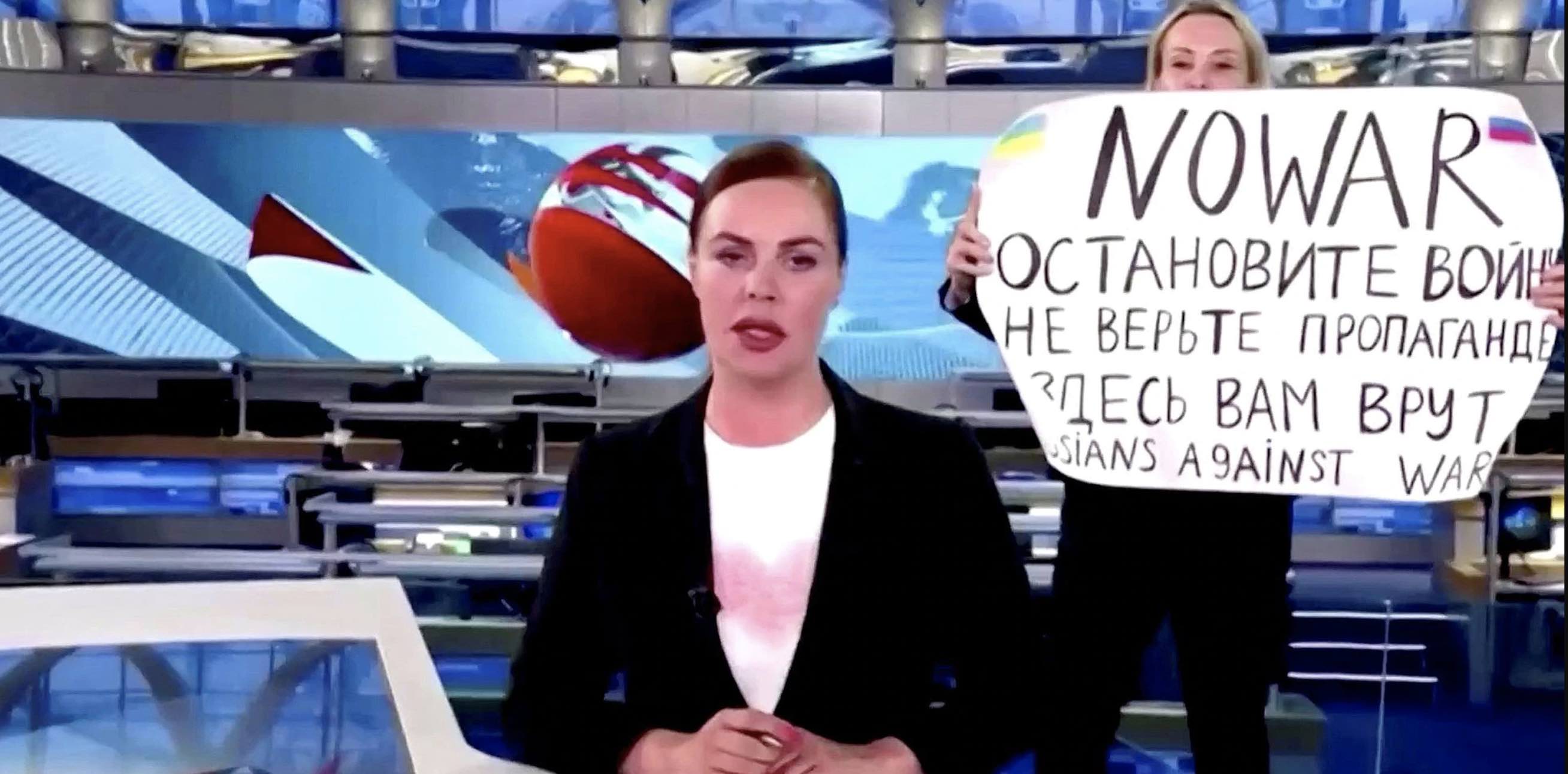

On March 14, Russian state television’s peak-time news programme, Vremya (Time), was interrupted by Marina Ovsyannikova, carrying a homemade placard denouncing the war and accusing the station of lying to the Russian people. Her protest was only visible for a few seconds, but it has had immense impact both across Russia and internationally and has given Russian opposition to the war a defining image – from within the heart of the establishment.

Ovsyannikova was no student protester. The 43-year-old mother of two was a longstanding television editor at Channel 1, the Kremlin’s propaganda flagship for Russia’s domestic audience. Just before making her protest, Ovsyannikova recorded a statement in which she spoke of her shame, as a half-Ukrainian, at her years at the propagandist channel during which she said she allowed Russian people to be “zombified”. She denounced Vladimir Putin as wholly responsible for the conflict and called on fellow Russians to join the protests against the war.

This was an extraordinary act given that a recently imposed law means that simply referring to the conflict as a “war” could mean a five-year prison sentence, and inciting protest could mean 15 years. These new laws led to the closure of most remaining independent media and the emigration of many of those who worked in it.

During the silence that followed her arrest, many on Twitter speculated that she might even have been killed and there were protests demanding news of her whereabouts.

She emerged, after 14 hours under interrogation, to a brief press conference. The following day she was given a relatively light fine of 30,000 rubles (£210). Three other journalists and presenters have resigned from Russian state television stations.

Although the court imposed the lightest possible penalty for the administrative offence, Ovsyannikova still faces the possibility of much more serious criminal charges based on the new article 276.3 of the Criminal Code, which could mean a sentence of between three and 15 years. Ovsyannikova has declared that she will not be leaving Russia, despite the possibility of jail.

Putin’s mouthpiece

Ovsyannikova’s protest needs to be understood in the context of Channel 1’s special role in Russia. It is not simply a channel that presents the government’s point of view. It goes much further, applying sophisticated PR techniques that were developed in the frenetic election campaigns of Russia’s democratic interlude in the 1990s.

It regularly uses staged debates, usually on topics relating to Ukraine or the West. Stooges are hired to present liberal or western viewpoints unconvincingly so they can be shouted down by the presenters or invited audience. The debates usually build to a cacophonous climax with many raucous voices shouting at each other. The emotional effect is to confuse and excite viewers and play on their fears and anxieties through an addictive cocktail of patriotism and paranoia.

Over the years, the station has had a powerful brainwashing effect – hence recent cases of Ukraine residents being unable to convince relatives in Russia that a war is going on – they are living in the alternate reality created by the channel.

TV as a political weapon

Weaponised television has played a crucial role in Russian politics since the early 1990s. The attempted coup of 1993 culminated in a bloody battle for the Channel 1 station at Ostankino, the television centre in Moscow. The same station was the key instrument of power wielded by arch-oligarch Boris Berezovsky in the 1990s, while his rival Vladimir Gusinsky launched NTV (Independent Television). Unlike Channel 1, NTV was renowned for its objectivity. Putin organised the seizure of both stations immediately on becoming president and control of the media narrative via television became a defining feature of his rule.

Also read: Putin’s Brazen Manipulation of Language Is a Perfect Example of Orwellian Doublespeak

Since the start of the invasion, there has been speculation over who within the Russian elite might be able to leverage an end to the war – this, rather than regime change, being the declared aim of sanctions. Some commentators have conjectured that sanctions would lead to the oligarchs exerting pressure on Putin. This was the model under Boris Yeltsin in the late 1990s when the president’s survival in power was seen to depend on a group of business leaders, notably Berezovsky. The subordination of the oligarchs was Putin’s main achievement in the early 2000s.

Others have wondered whether the siloviki, or security services, might intervene. But the siloviki are institutionally fragmented, and the sheer durability of the Putin regime has reinforced their conservatism and subordination to the president.

It is the state media that is the most powerful element in Putin’s system of government, applying its considerable artistry to secure the acquiescence of public opinion. Independent media have been marginalised as “foreign agents” and driven to broadcast from abroad or via social media, which in turn has increasingly been blocked by the authorities.

So it’s ironic that just as state TV attains a near monopoly over the dissemination of information, it one of their own who has used the station to promote the anti-war argument in the strongest possible terms and to the widest possible audience.

Putin is still in a position to command both oligarchs and siloviki. But the main anchor of his power is neither of these, but the state media. If elements in the state media begins to abandon or condemn the cause of war, then a tipping point in Russian opposition to the war may have been reached. Whether or when this will happen is another matter.

Adrian Campbell, Associate Professor, International Development, School of Government, University of Birmingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.