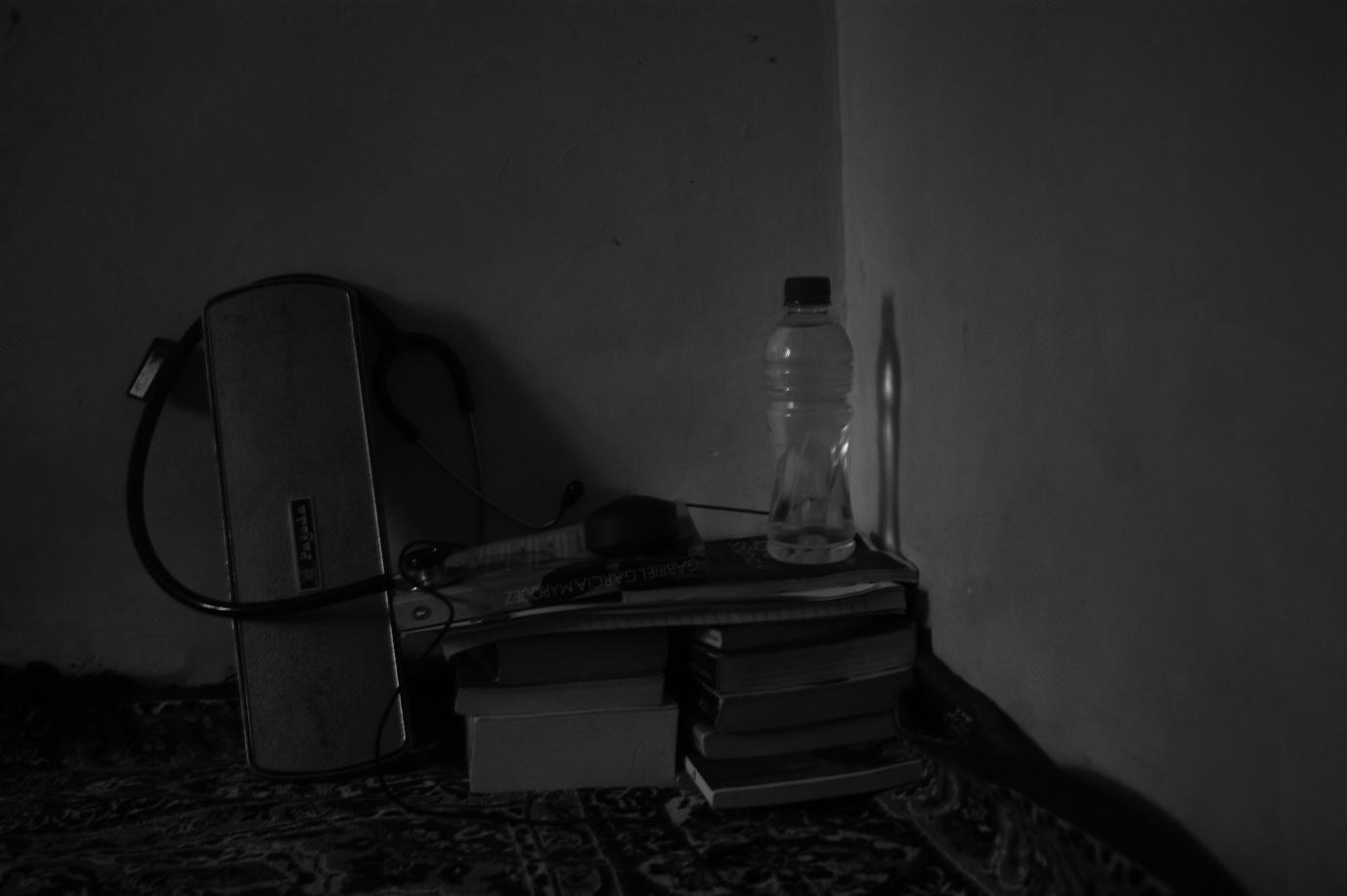

Some two years ago, when life was not confined indoors, you didn’t have time to form intimacy with objects that surround you. There you were, running amuck from one place to another, venturing out without hesitancy, without anxiety. So engrossed in life that you only came home to eat and sleep. Now when there are restrictions imposed upon your movements, you are forced to spend time inside, and constantly feel insignificant and lost amidst a pile of things that surround you and remind you of what it means to be confined.

You start observing small intricate details – like the movements of curtains when there is a breeze, and the passage of light through small creaks, and half-opened doors. You realise that boredom, like anxiety is physically painful, and escape into the dark mazes of social networking sites, until you get bored from that as well. You are forced to confront your fears, and most of the times, you are afraid of your own palpitations. You are so afraid of the death looming around that you start fearing everything that reminds you of life, like the complex unreliable machinery that is working inside your body, recklessly.

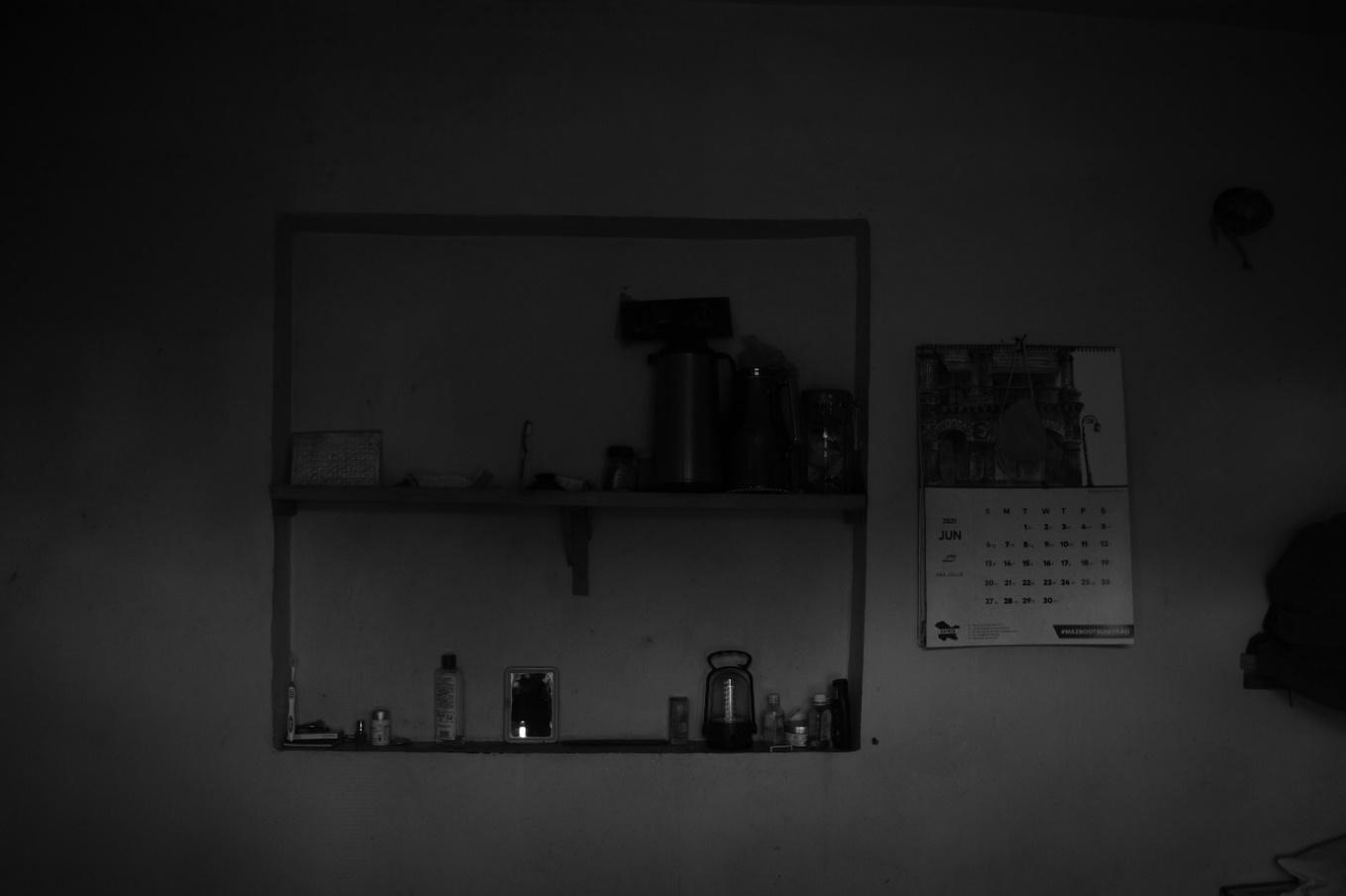

The days are long and tiring, even though you engage in minimal activities. Sometimes, you happen to look at the calendar, and its monotonous numbers that bring no change into your life.

For the first time in life, you observe the idiosyncrasies of those who surround you. You observe their movements, their fears, and their silent noble struggle against time. It pains you to see that the health of your family members is deteriorating, and they’ve become increasingly dependent on medicines. Blood pressure and sugar tests have become routine.

These are tough times to be in, and you find yourself engrossed in screens to attend classes, and also, very absurdly, to appear for exams. If you are a student, most of your time is spent doing assignments, which give rise to habitual headaches. Sometimes, it seems absurd. With so many people dying around, so many without food and shelter, you are asked to work like a maniac and meet assignment deadlines. You are afraid that in a ruthless capitalistic world, no time will be left for mourning.

Also read: Buri – My Grandmother’s Eternal Lockdown

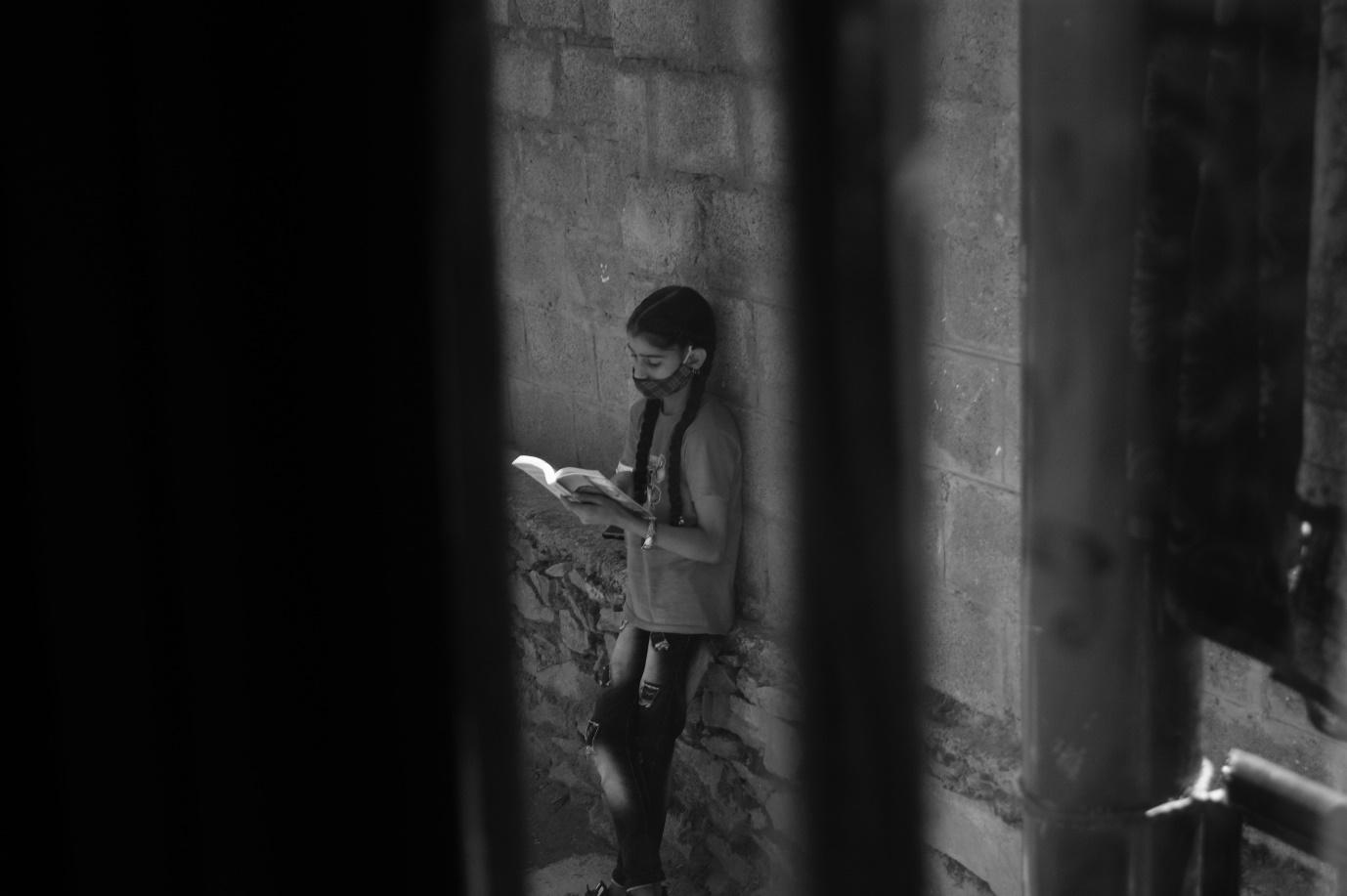

When it rains, you find yourself looking through windows, which have donned the role of portals that help you access the world outside, and think about the past and the future. As for the present, it is lost among those insignificant things that go on to make a home. You can hear your mother, humming in a soft voice inside the kitchen, while she prepares food in an almost robotic way. You also hear the muezzins that announce the greatness of God, regularly, five times a day.

During the evenings, in that liminal space between the day and night, you observe thin poplars dancing to the breeze, offering white pollen which try desperately to masquerade as snow, as they fall, inconspicuously, brightened by bulbs dangling from electric poles. It offers a brief respite from arguments that have increasingly come to characterise your life. You are irritated most of the times, and fall into pointless arguments with those that surround you.

But most importantly, you empathise with those who spend most of their lives inside the four walls of a house.

There is despair, but there is also hope. You hope that the world that emerges out of the pandemic will be a little less miserable. The value of life, and of movements not restricted by time and space, has dawned upon you.

Sameem Wani is a postgraduate student of English at Ashoka university. He is presently based in Kashmir.