Jojo Rabbit is not Disney Studios’ first foray into Hitler parody. In 1943, it produced der Fuehrer’s Face – an anti-Nazi film inside Donald Duck’s nightmares.

Now, Disney is the Australian distributor of Jojo Rabbit, a story of a young boy whose imaginary friend (and buffoonish life coach) is Adolf Hitler.

In this dark satire, from the Polynesian-Jewish-New Zealand director Taika Waititi who brought us Hunt for the Wilderpeople, Nazi Germany is in its waning days. The Germans have all but lost the second world war but 10-year-old Johannes “Jojo” Betzel (Roman Griffin Davis) believes he, and he alone, will be the Aryan hero to turn the tide.

The boy’s imaginary friend, a hilariously incompetent Hitler (played by Waititi in blue contact lenses and the trademark moustache), cheers him on. When asked to kill a rabbit to get into the Hitler Youth, Jojo baulks, though he does almost manage to kill himself in a grenade stunt.

“You’re still the bestest, most loyal little Nazi I’ve ever met,” the fantasy Fuhrer enthuses.

Through children’s eyes

Themes and images of children have often been central in films exploring WWII. Steven Spielberg famously used “the girl in red coat” to create a powerfully moving symbol of innocence in Schindler’s List (1993).

Immediately after the war, a stream of films, including Roberto Rosselini’s Germany Year Zero (1948), Gerhard Lamprecht’s Somewhere in Berlin (1946), and Fred Zinnemann’s The Search (1948) looked at wartime trauma through injuries acquired by children.

Like Jojo’s grenade mishap, their wounds were permanent.

In war films, children’s perspectives don’t diminish the ghastliness of war. Quite the contrary. When war and its pervasive horror spills over from the battlefield and intrudes on their youth, viewers are appalled at its spread.

Containing that disease of war, curing it even, is where Waititi’s takedown of fascist group-think truly begins.

How will Jojo escape the brainwash army of Reichswehr propaganda parrots like Rebel Wilson’s Fräulein?

There are several steps. The first one for Jojo is finding out his mother has been hiding a Jewish girl in the attic.

Scarlett Johansson gives an enchanting performance as a single mum who tries to keep the embers of humanity and love in Jojo’s heart alive as he gets lost in Nazi doctrines of vile anti-Semitism.

Jojo starts falling for Elsa Korr (Thomasin McKenzie), the hideaway in his attic, as her humanity – and his pre-pubescent hormones – triumph over fascist indoctrination. Through Jojo’s eyes, we see Elsa turn from monster into human as he comes back from the brink of fanatic hatred.

Waititi hides that innocent, simple love story under slapstick and a ton of special effects. The latter don’t always work. And some of the jokes fall flat.

But what works is the message that Jojo is both manipulated and self-manipulating. His Nazi hate is a cage of his own making, and Elsa is the key to unlocking it. She teaches him that empathy for those who we think are different from us is powerful.

Irreverent or irresponsible?

Hitler comedies have a long history. In 1940, Charlie Chaplin released The Great Dictator. Mel Brooks created The Producers in 1968.

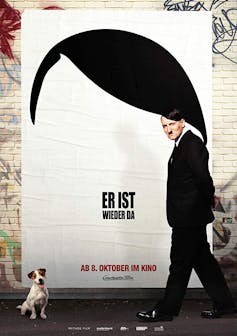

In Look Who’s Back, Hitler wakes up in the 21st Century. Image credit: Constantin Film

German filmmakers Dani Levy (My Führer – The Really Truest Truth about Adolf Hitler, 2007) and David Wnendt (Look Who’s Back, 2015) strived to find the right balance between comedy and drama.

Like Waititi, those filmmakers experienced how mining sombre Holocaust themes and hateful iconography for the ridiculous splits public reactions along extreme lines. The critics bemoaned that Levy committed only halfheartedly to a funny Hitler, making the film the worst thing a comedy can be: too harmless.

Wnendt faced another issue. He intercut his film with hidden camera footage of Germans reacting to the lead actor dressed as Hitler. People thought this was too much realism.

Waititi says he didn’t look at these forerunners and didn’t do any research on Hitler. He looked to literature instead.

Jojo Rabbit uses the masterful dramatic novel Caging Skies by New Zealand-Belgian author Christine Leuens as source material. The book doesn’t have the same generous scoops of comedy and tragedy found in Ladislav Fuks’ Mr. Theodore Mundstock, or in The Nazi and the Barber by Edgar Hilsenrath.

It’s all the more reason to recognise what Waititi has tried to accomplish. He had to negotiate between a book adaptation, Holocaust memory, and Hollywood.

Commenting on his motivation for making the film, Watiti, whose mother is Jewish, said: “I just want people to be more tolerant and spread more love and less hate”.

Benjamin Nickl, Lecturer in International Comparative Literature and Translation Studies, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.