“They have guns, we have gaan (song)!”

Theatrician Joyraj Bhattacharjee’s booming baritone reverberated across the Academy of Fine Arts auditorium in Kolkata. It summed up the theme of the evening’s concert ‘Buland Iraadein’, organised in solidarity with the farmers’ movement, on January 29.

The fiery concert, which I happened to attend, came at a time when emotions in the state were already inching towards being supercharged in light of the upcoming assembly elections that are now nearly upon us.

The opening act – the Arko Mukhaerjee Collective – set a fiery mood with a protest song which called for fighting for one’s land. Bengali folk rhythms played on a guitar and ukulele went up several notches with every stanza, building up to an ominous soundscape. Blue and pink lights flashed on the stage’s black curtain as the vocal choir, composed of the Titimir Collective, joined the roaring chorus of ‘Lorai chharbo na, NA! (Won’t give up the fight, NO!)’.

Arko Mukhaerjee Collective with the choir.

The lyrics of the songs mostly centred around farmers, the common man and the soil. Huge applause accompanied the folk number ‘Mero Gaam Katha Parey’ from Shyam Benegal’s movie Manthan – inspired by Verghese Kurien’s Operation Flood, which made India’s milk industry self-sustaining and the world’s largest producer.

The soundscape was bolstered by three percussionists who played African and Bengali folk instruments such as djembe, bongos, cajon, frame drum and nagara, dhak, dhol. Naturally, the rhythms were rich, layered and thumping. This shaped the visual part of the performance where several dancers enacted the songs.

The choice of songs was not random. They were designed to support the cause that Bhattacharjee and team are fighting for. In fact, the dynamic theatrician had visited the Singhu border twice. He made the second journey on foot with three other companions. They walked through Bengal, Jharkhand and Bihar, avoiding Uttar Pradesh as that might have proven risky.

“We raised awareness about the farmers’ protest in all the provinces we crossed on the way to Delhi from Bengal. We stuck to the highways where protests were happening and got people to join us on the journey,” he said, further adding that the concert series was started during the lockdown as online events. Ticket sales permitted them to run a community kitchen – Priyo Manna Bastee – where poor people are given meals at a nominal price. He also donated Rs 1 lakh from the canteen’s fund for the farmers’ movement.

But ‘Buland Iraadein’ has loftier goals than just philanthropy and aims to continue the series throughout the year. Bhattacharjee said, “This year marks the 75th anniversary of the end of fascism in Italy and Germany. We are celebrating that while also protesting its rise in India.”

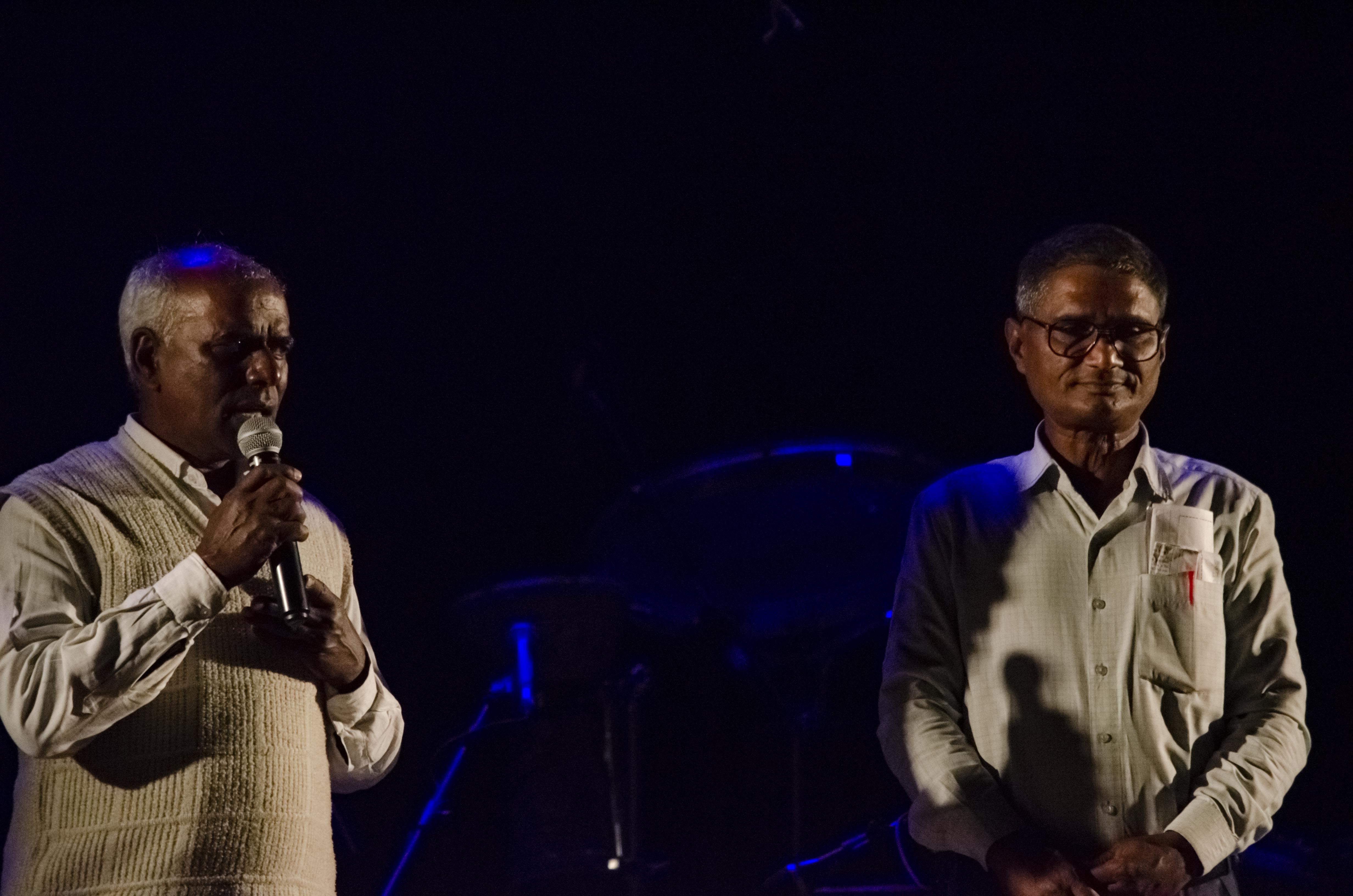

His ambitious march not only garnered support from various rural groups, but also resulted in two persons from Masaurhi, Bihar – farm leader Sona Lal Prasad and poet Adhesh Kumar – participating in the concert.

Farm leader Sona Lal Prasad and poet Adhesh Kumar.

The former, representing ‘Farmers of Bihar and India’, minced no words in calling out the apathy of the government towards farmers. “The PM says the farm laws are for farmers’ benefit, but then why are farmers protesting? This movement is a crucial fight. The government is making laws so that corporates like Adani and Ambani can profit,” he said, with a premonition that future scenarios would become similar to the Bengal famine of 1943 which killed nearly 30 lakh people. “Grains were stored in the godowns run by the British but not brought to the market. Today, godowns are being built across the country and it will become the same.”

To such a fiery template, Kumar added fuel with the words: “If saying the truth is a crime, I’m a criminal.” A proponent of the Magahi language, his satirical, protest poetry crossed the language barrier to elicit laughs and raucous applause as he ridiculed, challenged and called out the government.

When he took a dig at India’s ‘vikas’ over the last few years, the audience erupted in roars. He also touched upon themes of women empowerment, double-faced tactics of politicians, finally ending with the warning: “Those who snatch food from the poor, for them, this theatre and song is trouble.”

Dancer Srabanti Bhattacharya defied norms during her performance by dancing Odissi on an Urdu song wearing a black saree, without dedicating it to Lord Jagannath.

The flame was fanned again by Mukhaerjee as he injected Cuban protest songs into his second set with ‘Hasta Siempre, Comandante’ and the patriotic song ‘Guantanemera’. The former is an ode to Cuban Revolution leader Che Guevera and was sung in the streets of Cuba after his death. The latter, taken from Jose Marti’s poem ‘Versos Sencillos’, talks about a peasant who wants to live and die in his own land. This was clubbed with the ballad ‘Haay Bhalobashi’ by Bengali band Mohiner Ghoraguli, which has a rural ethos.

Mukhaerjee in action.

Mukhaerjee also directed the audience to clap to the rhythm of the stirring anthem ‘Pothey Ebaar Namo Saathi’, penned by legendary music director Salil Chowdhury. This blended into ‘Kadam Kadam Badhaye Jaa’, where the crowd joined in. The combined effect of the marching rhythm, clapping and enthused voices was feverishly intense. A photograph cast on the white wall showed a group of protesters holding a placard with the words ‘Inquilab Zindabad’ written in red, and below ‘Down with Modi-Shah Fascism’.

But this was puny compared to how Borno Anonyo worked the crowd with their starkly political songs. Satyaki Banerjee, multi-instrumentalist and vocalist, was especially a force. Hands raised, fingers curled into tight fists and voice thundering across the hall, he urged the crowd to stand and fight.

“When the revolution gets tired, it takes the form of a prayer. From there, agun pakhi (fire bird/phoenix) is born,” he said, before delving into their original composition ‘Prarthona’. Two guitars, bass, violin, dotara and assorted percussion instruments worked up a soundscape that was equal parts beautiful, daunting, cacophonous and melodic.

From ‘Hum Dekhenge’ to ‘Laal ey Laal’, the band called for resistance. The crowd lay transfixed during the songs, while erupting in applause at their endings. However, when the last song was being performed, no one could resist joining in as they sang: ‘Rajar dorja teh toka, raja shuntei pabe na’. (Knock on the king’s door, he won’t be able to hear you).

Drawing parallels to political leaders who do not care about the common man, this song found resonance in the predominantly Bengali crowd which had been under Left rule for 34 years. When the nearly full 730-seater auditorium joined the band in chanting ‘Left, left, left-right-left; left, left, left beats right’, one could almost sense a trickle of cold sweat dripping down the backs of the powerful in Delhi.

Shaswata Kundu Chaudhuri is a features journalist based in Kolkata with an unhealthy interest in music.

Featured image: Borno Anonyo

All images have been sourced and provided by the author.