Memsahibs in British India travelled extensively to accompany their husbands on official Raj duty, or to explore the country and witness the ‘orient’ by themselves as tourists. Some of the boldest journeys undertaken by them were for the mere sake of escaping their monotonous lives as wives of the sahibs, and seek diversion through thrilling excursions across the largely uncharted terrains of the Raj.

Memsahibs were known to share the sahibs’ affinity for travel and did not hesitate to participate in sporting holidays — something that they could not do back home in England where Victorian mores of social propriety were strictly enforced. The social freedom frequently allowed them to step into the masculine terrains and travel on precarious side-saddles for days on shikars and expeditions, dressed in manly sola topees and khakis. Memsahibs like Monica Lang travelled with her husband to the border of Tibet to take in the scenic beauty and fish in the lakes.

If they did not enjoy sporting activities, they liked to sightsee. Sometimes, memsahibs, accompanying their husbands on official visits, visited palaces of kings and queens to take in the exotic and luxuriant side of India. Lady Wellington was presented with purpled-dyed toilet paper once by the Maharajah of Baroda simply because she liked the colour. Memsahibs were, therefore, fascinated by the exuberance of the Rajas and Maharajas’ extravagant lifestyles, and their generous and grand hospitality. They relished the delicacies meant for royalty, and enjoyed the performances of the courtly nautch-girls. As women, memsahibs could even enter into the exclusive zenanas of the queens and princesses — something that the sahibs were never permitted to do.

It must be noted that memsahibs were often solo travellers who toured extensively for the sake of pleasure and recreation. They also journeyed to escape the summer heat in the plains where their husbands were stationed, to retire into the hills until the climate became temperate enough for them to return. Flora Annie Steel, the wife of an ICS officer, went on independent adventures leaving her husband behind.

Also read: Shakespeare, Nostalgia and Memsahibs: Four Decades of ’36 Chowringhee Lane’

Adventure was something memsahibs craved as they were denied it back home. In any case, colonialists had always been fascinated with the architecture of the East and the natural wonders found here. They trekked in pursuit of wondrous Shangri-las for weeks, waded through swelling rivers, braved the jungles, and tolerated all the trials and travails of the tropical climate, sometimes simply for the passion for travel. Emily Eden, for instance, famously styled herself as an ethnographer and went ‘in search of the picturesque’, revealing her enlightenment curiosity.

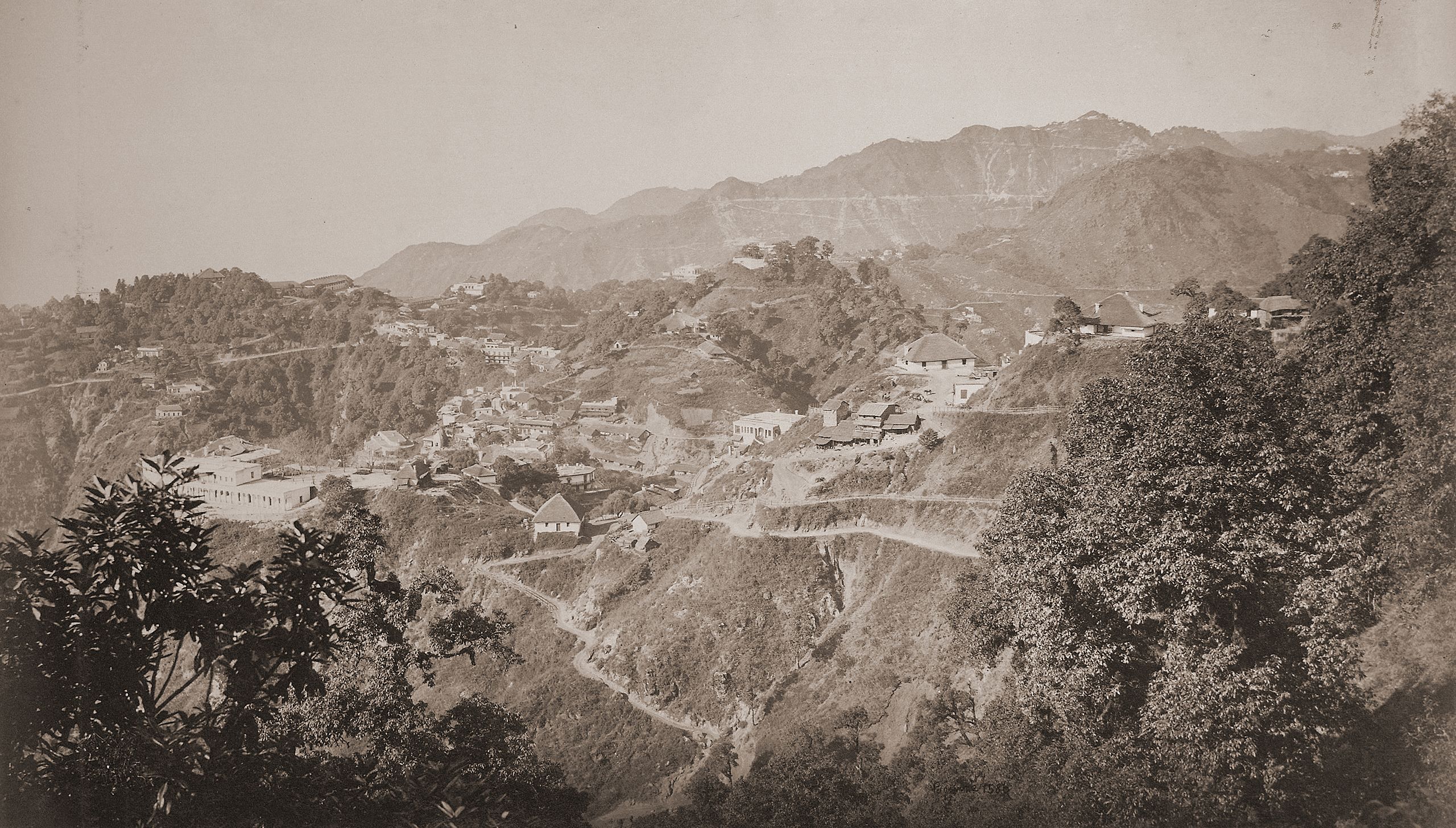

Tourism was so widespread in British India that by the end of the colonial rule, there were multiple hill stations that had been summer establishments for memsahibs and their children, and that are still tourist attractions today. However, travels were not always about thrill and adventure. Accompanying the sahibs meant that the women were mostly in charge of the enormous quantities of baggage and supplies as well as the management of servants. Sometimes, women had infants or young children to take care of and this added to the risks and troubles. Although camps were generally large and luxuriant, with silverware and candlesticks for dinner tables, pictures hanging on walls, rugs on the floor, and canned food cooked with locally available items, it wasn’t always easy living in the middle of jungle. Memsahibs perused the variety of self-help books and manuals for such journeys, written by experienced memsahibs, to ensure a smooth experience.

It cannot be denied that travel was mostly difficult, burdensome, and sometimes times even life-threatening. There weren’t too many options for modes of travel, and the ones available were acutely uncomfortable and perilous, even though they had access to government services that Indians did not. Europeans were expected to travel first or second class only as it was deemed too risky to mingle with the Indian masses. And despite the privileges, travelling was slow and dangerous. Carriages were far too jolty and so were palanquins.

Apart from the rough terrain, there was the fear of thugs and dacoits too. This is portrayed in John Masters’ The Lotus and the Wind (1953), as the heroine witnessed the murder of an Afghan while journeying to a British military post at Peshawar. Boat travels were similarly dangerous because the coast was dangerous and Indian rivers could swell up unexpectedly.

Things changed with the second half of the nineteenth century with railways and steamships. But there was still several disadvantages. Memsahibs’ letters and accounts such as that of Minnie Blane, Ellen Beames, and Margaret Smith indicate that travelling and the harsh climate of India led to gynaecological and obstetrical problems. Moreover, there was always the lurking fear that Indian men were lustful and capable of raping them. A Passage of India captures this fear amongst the British, especially British women, who strongly imagined a threat from Indian men. Laura Donaldson calls it the “Miranda Complex” while commenting on to the fear amongst memsahibs that the colonised men desired their bodies and would ‘ravage’ them if they had the opportunity. Nancy L. Paxton has accurately stated in Writing Under the Raj, “The rape of the colonising woman by a native man is the master trope of colonial discourse.”

Nonetheless, memsahibs in colonial India indeed displayed a keen spirit for adventure. It must be stated that in the pandemic era, people braving the infection during a deadly outbreak seem to be doing it with an all too familiar desire for diversion and adventure. It seems there has always been some sort of a mysterious alluring pull of distant lands that make people undertake journeys despite the dangers involved. Although, given the deadly nature of the virus, it might be prudent to rein it in for sometime — even if the memsahibs of British India hardly ever did.

Ipshita Nath teaches English Literature at University of Delhi. Her book of short stories, The Rickshaw Reveries, came out in 2020.