Writing at a time when the act of writing itself was a transgression for women, Ismat Chughtai won the title of ‘Urdu’s Wicked Woman’ for her exploration of avant-garde subjects such as femininity and female desire in her work. A critic of middle-class gentility and the circumscribed positions relegated to women in bourgeois households, Chughtai’s writing edged on the revolutionary for bringing attention to the zanan and the zenana – the woman and the female space – in a largely phallocentric culture.

Traditionally, the zenana referred to the inner apartments prescribed for women in houses belonging to Muslim or Hindu families up to the 20th century. Intended as a space for confinement and segregation by the patriarchal family structure, the zenana also came to be understood as the female sanctuary – a place where women could express themselves without the fear of men.

It is this latter, more romanticised understanding of the female space that Chughtai dextrously undercuts in her notorious short story, Lihaaf. The story centres around a young Begum Jaan who is married off by her parents to an aristocratic Nawab, a seemingly charitable man who is known for his good character. His ostensible virtue, however, is a consequence of his hidden homosexuality. He exercises this identity under the garb of a ‘strange hobby’ – entertaining young boys in his household whose educational expenses were picked up by him.

Begum Jaan then finds herself trapped in a lonely marriage, where the Nawab refuses to acknowledge the existence or the legitimacy of her sexual desire. It is through her emancipation within the female space, the inner quarters, that she regains her autonomy. A beaten down Begum Jaan finds solace in the ‘special oil massage,’ a metonym for sexual service, that she extorts from her maid Rabbu. While the story is widely celebrated for the Begum Jaan’s reclamation of her desire and authority through the zenana, the oppressive nature of this act is often glossed over.

Begum Jaan’s choice of Rabbu does not arise from a homoerotic desire on her part, it is rather the societal power dynamics that inform her choice. The popular readings of the story celebrating its advocation of female desire and same sex relationships in a space free from the patriarchal diktats ignore that the relationship arises not from a feminist solidarity, but as a symptom of the power structure that pervades even gendered relations.

Begum Jaan must find her sexual servant in one that occupies a lower social position than that of hers. This mandate automatically rules out all men, simply by virtue of gender supremacy, and then also all women of her social class. Rabbu, the masseuse, fits this criterion. She offers her services to Begum Jaan not out of love or desire, but due to her straitened socio-economic position – the Begum buys her son a shop and gets him a job in the village, plausibly in exchange for her services. The seemingly isolated safe space of the women then directly reflects the outer world – the Nawab’s drawing room wherein he exploits young boys under the veneer of charity.

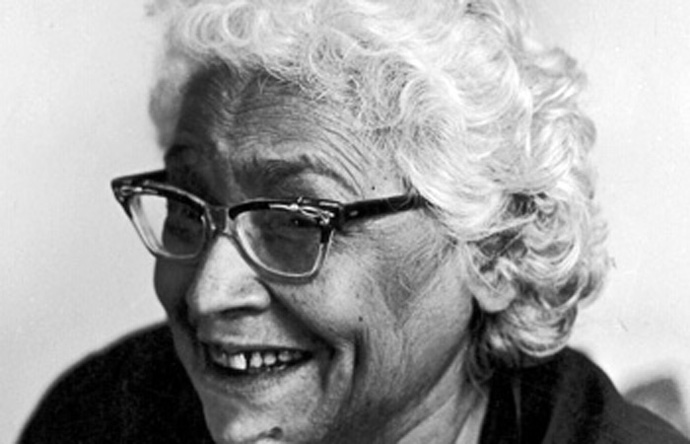

Also read: Remembering Ismat Chughtai, Urdu’s Wicked Woman

Chughtai, recounting this childhood incident as an adult, brings out the irony of the perceived safety of the female space in those times – the glorified zenana – which takes into account only the gender difference and division, but remains oblivious to the hierarchies that operate within gendered environments as well. Elaborating on this thought, the narrator says:

“Amma always disliked my playing with young boys…She was a believer in strict segregation for women. But Begum Jaan here was more terrifying than all of the loafers of the world.”

As a lay reader approaches the story, it does not come across as the critically valorised celebration of the zenana and female desire as advocated by Khanna, Thakur and others, but one that strips the facade of a collective female subjectivity and sanctuary.

While today zenanas may be long gone and forgotten, Chughtai’s rendition of the fragmented nature of female spaces remains starkly relevant. Women’s colleges, for instance, carry the tradition of being gendered spaces that provide a safe environment for women, where they can thrive away from gendered roles and the male gaze that pervades social situations.

These institutions are touted as havens where there is strong feminist solidarity and sisterhood. What remains hidden to the eye is the inequalities that plague the internal dynamics of such institutions as well. The positions of merit, for instance, in feminist-progressive colleges like Lady Shri Ram College and Miranda House, are occupied of course solely by women, but also almost exclusively by women belonging to a higher caste, class and socio-economic background. These are the factors that lie behind and contribute to the making of one’s merit, that is loosely based on one’s fluency in English, a good schooling, and a self-esteem untarnished by the experience of societal subordination.

Within such spaces as well, the experiences of women then differ greatly based on their hierarchical locations and social parameters, undercutting the larger advertisement of feminist collectivity that is posited. While the hierarchies may no longer be as glaringly evident as they were in the case with Begum Jaan and her maidservant, they continue to thrive nevertheless and retain the positions of authority for the privileged. The modern-day zenana then continues to be as relevant and fractured as it was in Chughtai’s time, and its claims to a feminist solidarity remain as incomplete.

Saadhya Mohan is an English Literature student at Lady Shri Ram College for Women. She spends her days reading a lot, writing a little, and drinking dangerous amounts of green tea.

Featured image: Wikimedia Commons