Fifteen minutes into the physics period, and my eyes were already glassy with boredom. I spun my head around to find my friend hiding under her desk, eyes glued to a book.

“Psst… What are you reading?” I whispered.

She enthusiastically held up the book, “It’s a romance!”

I forced a smile and let the conversation die.

You see, normally, I would have followed up with questions – what’s it about? Do you like it? Could I borrow it?

But, this was different.

Growing up in a world of books, I knew that the romance genre was considered the lowest form of literature. Romance novels, with their ludicrous covers and depthless plots, were unintelligent and misogynistic – simply ‘trash’.

At best, they were pallet cleansers meant to be read between “real” literary works. So, I’d never even come as close to reading the synopsis of a romance novel.

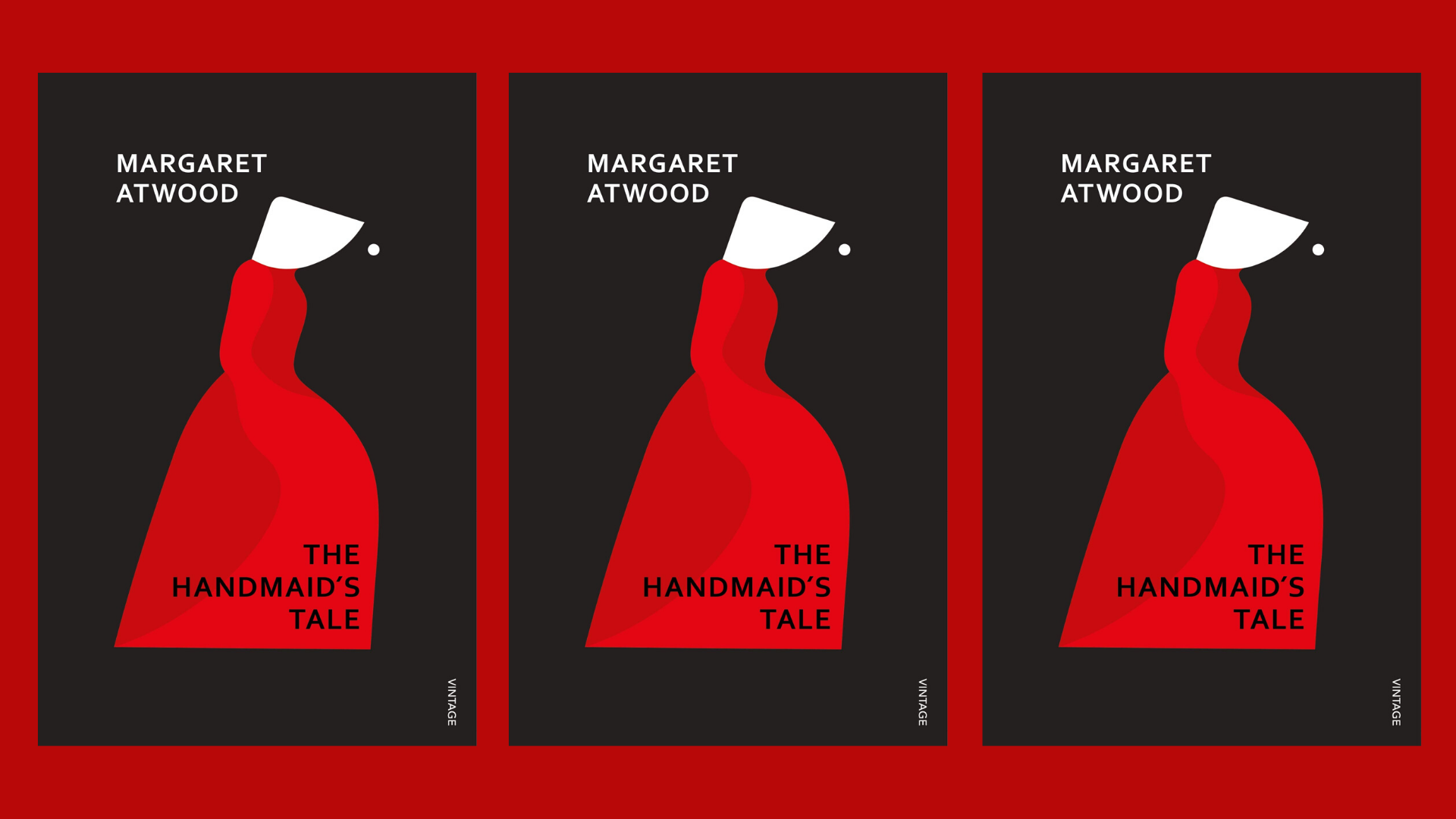

Last summer, I began reading Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. It’s a speculative fiction set in Gilead, a radically conservative state. Gilead showed complete disdain for women’s right to education, freedom of expression and bodily autonomy. The story revolves around June who, along with other handmaids, breaks many laws in search of individuality and freedom.

Also read: On Reading Nivedita Menon’s ‘Seeing Like a Feminist’ in a Patriarchal Home

When the romance between June and Nick was first hinted upon, I assumed it would act as a buffer to what was a rather grim plot.

Boy, was I mistaken.

After multiple chapters unfolding instances of murder, legalised rapes and toxic masculinity, their relationship was a breath of fresh air. In a world where men decided whom to have sex with, June chose Nick. A woman, who was continually subjected to emotional and sexual turmoil, reclaimed her body. By doing so, she reclaimed a part of her freedom. June finally had someone she trusted, someone she could feel safe around, someone who respected her. Nick was the family she longed for.

The ‘romance’ contributed to an integral theme of the story – free agency. Without it, the book would be incomplete.

Us feminists have fought a lot of fiction for reducing women to a trope where they must get married and have children to achieve fulfilment. Then why do we continue to subconsciously think that they must end up single to be classified as bold, fierce and independent?

I then started to think about why I’ve condemned romantic literature for so long. I realised that my internalised misogyny made me believe that romance wasn’t worthy of being honoured – especially in books about science and politics. Perhaps, it’s because romance is largely female dominated. It’s written by women, on women, and for women. Good romances openly explore female sexuality and desire – subjects that are stigmatised and considered embarrassing in most cultures. Most other genres also cater to the male gaze and are written from male POVs. In a way, romance is peak feminist literature.

Also read: Emily Dickinson and the Unforgivable Crime of Women Liking Their Own Company Too Much

That being said, it’s also important to remember that romance, like any other genre, is flawed. It often reinforces the “damsel in distress” stereotype, makes young girls believe that women are only interesting as potential romantic partners, and objectifies women.

But even though not every female character needs a lover, June’s healing needed some love. I was foolish to think otherwise.

These past few months, I’ve noticed more and more how internalised sexism affects me, and how broken my feminism is because of it. Somewhere along the lines, I distanced myself from everything remotely feminine. I began placing myself on the same toxic pedestal I had strived to remove other women from.

I’m the feminist who gave passionate speeches on glass ceilings and capitalism. I was the 16-year-old who called editors to take down sexist chapters from school textbooks. I attended climate marches and emailed local politicians to demand action.

But I’m also the girl who has linked self-worth with appearance. So I refuse to learn how to apply makeup because I fear there’ll come a time when I won’t be able to look at myself in the mirror without it. My feminism is way less intersectional than I like to admit. I feel hesitant while being assertive. The man inside my head still refuses to be policed, so I’m always too political, too feminist, too skinny, too loud and not enough at the same time.

I’m finally erasing this beautified, woke, near perfect version of myself. I’m standing in solidarity with people who’re fighting their internalised misogyny.

Rhea Khandelwal is a recent high school graduate who aspires to become a traveller, writer and research psychologist.