Rush Limbaugh’s first book, The Way Things Ought To Be, came out in 1992. Bernie Sanders was an obscure first-term congressman. The democratic socialists of America was a tiny fraction of its current size. The Cold War was over. Yet Limbaugh, who died this week at the age of 70, devoted a full chapter of his book to the dangers posed by “socialist utopians” advocating “national health care.” He didn’t quote any of these utopians, or name any names. He didn’t discuss the experience of countries that already had “national health care.”

He simply asserted as fact that if we “turn[ed] over” the health care system “to the government,” the result would have “the efficiency of the Post Office and the bedside manner of the IRS.” The line was vintage Limbaugh — comedic and boisterous and completely nonsensical. Government-run health insurance programs are more efficient than private sector equivalents. Residents of nations with “national health care” live longer than we do, have fewer of their children die as infants, and have generally better rates of “mortality amenable to health care.” They don’t stay in jobs or even marriages they hate out of fear of losing their insurance.

Reading or listening to Limbaugh, anyone who knew anything about the history of social democracy would be left muttering to themselves with irritation.

And that, of course, was half the point. The image Limbaugh projected was of someone who wasn’t obsessed with politics but who felt moved by the absurdities he saw and used his humor and intelligence to, as we would put it today, trigger the libs. This in turn helped his fan base see themselves in the same light.

Reducing progressives to sputtering consternation was the entire goal — or at least it was for Limbaugh. The plutocrats who owned the hundreds of radio stations that broadcast his message every day had bigger fish to fry.

Jeff Christie and Rush Limbaugh

Limbaugh’s radio career began in the 1970s. Back then, he was an apolitical DJ who called himself “Jeff Christie.” If you listen to those clips, you can hear “Christie” talking about “serving humanity” from his radio station in Pittsburgh. He told his listeners that he “shouldn’t have to tell them” how great the Stevie Wonder track he was introducing was and how important it was for them to listen to it. All of that sounds a lot like the Limbaugh who would be nationally syndicated under his own name in 1988 — the one who spoke from behind a “golden microphone” with half of his brain “tied behind his back just to make it fair.”

But by 1988 he was combining this over-the-top and charmingly absurd self-promotional schtick with an aggressive and cruel brand of right-wing politics. He was more or less openly racist. He tried out a bit in 1990 called the AIDS Update, where he played “Looking for Love in the Wrong Places” while mocking people who were dying excruciating deaths. (He later apologised.) And he was a relentless opponent of unions, comparing them to “mafia fetuses” and fuming about “union thugs” who were trying to “steal” from taxpayers by bargaining for higher wages in the public sector.

If he’d been syndicated two years earlier, all of this would have generated endless headaches for his bosses. The “Fairness Doctrine” — enforced by the federal communications commission until 1987 — mandated that the private corporations that leased the public’s airwaves couldn’t provide commentary on controversial subjects without giving airtime to contrasting views. Once this doctrine was scrapped, companies were free to build the talk radio landscape we know today.

Limbaugh’s victory

Limbaugh’s show used to air from noon to three every day on my local AM station in mid-Michigan. Sean Hannity was on from three to six and second- or third-tier conservative hosts filled the remaining hours until “Coast to Coast,” whose hosts talked about aliens and paranormal events more than politics, came on at midnight.

As a student and antiwar activist in my early twenties, I listened to a lot of talk radio in the car. Part of it was about knowing the enemy. Part of it was just that, other than NPR, gospel radio, and various music stations, there weren’t a lot of options. And in Limbaugh’s case, as despicable as I found his views and infuriating as I found many of the things he said, the truth was that listening to him could be fun.

Sean Hannity always sounded like the kind of guy who wouldn’t skip a beat if you woke him up at four in the morning. His eyes would open and the first thing out of his mouth would be a rant about how liberals loved Saddam Hussein. He did this thing where callers would tell him he was a great American and he would respond, “No, sir, you are a great American,” and you could practically hear them snapping to attention and saluting each other.

Limbaugh wasn’t like that. He loved to go off topic, chattering about football or entertainment, and I often heard him mock the segment of his audience that didn’t like when he did that — “the ‘stick to the issues’ crowd.” His show started with inviting, upbeat music. He’d call himself “El Rushbo” and talk about how he was smoking cigars. He’d do his routine about being in a “bunker” representing the “southern command center” of a fictional EIB (“Excellence in Broadcasting”) network.

None of this made him a Lenny Bruce–level comic genius, but the overall effect was warm and inviting. It made his digs at liberals seem less like angry recitation of talking points than just telling it like it was and having a little subversive fun.

And he was very, very good at it. Between 1988 and 2016, he not only created the kind of talk radio we know today but built an audience that was thoroughly primed for the kind of thing Donald Trump would offer them — an endless meandering monologue, mixing comedy with demagoguery and trading on the idea that the audience was collaborating with the performer to make liberals cry.

Where the most prominent figure in conservative media used to be Yale graduate William F. Buckley, who spoke in a posh faux-English accent as he intellectually fenced with people like democratic socialist Michael Harrington, Limbaugh was essentially a calmer and more self-aware Trump in his personal style. If he wasn’t exactly Trumpist in his personal politics, that’s because he had few if any real political principles.

The last two Republican presidents openly hated each other, but both effusively praised Limbaugh. And why wouldn’t they be grateful? He was equally happy to whip up the GOP base for God, Country, and George W. Bush in 2004 and for Trump’s War Against the Deep State in 2016 and 2020 — even if that meant that he was a tireless apologist for the Iraq War when I used to drive around Lansing, Michigan listening to him in 2003, and by 2020 he was suggesting that Democrats in the deep state had tricked Bush into invading Iraq.

Cockburn vs Limbaugh

The late Alexander Cockburn called Limbaugh the “dirigible of drivel.” That’s certainly accurate. Limbaugh was fond of arguing, for example, that anthropogenic climate change couldn’t be a serious problem. After all, he reasoned, God created nature and so it would be impossible for mere humans to do anything to disrupt it. “[I]f you believe in God then intellectually you can’t believe in manmade global warming.”

It should take about thirty seconds to realise that an exactly parallel argument could be made about nuclear war. If God created humanity, surely He wouldn’t let us destroy ourselves in an atomic exchange. One wonders why Limbaugh’s idol Ronald Reagan was so intent on creating a missile defense shield.

Limbaugh’s frequent claim that poverty was caused by a “dependency mentality” and a failure to instill the poor with a spirit of ambition and self-reliance made similarly little sense. If the whole point of ambition is to climb the ladder of a hierarchical economic system, it’s impossible by definition for everyone to escape poverty that way.

But these responses are almost beside the point. While there’s certainly a role for debunking the bad arguments of right-wing blowhards, the point of Limbaugh’s bizarre chains of reasoning was to tell his listeners a story about the world that struck a chord and made them feel good about themselves. You might have a crappy job, but at least you’re not one of those moochers looking for a handout. Don’t worry about climate change — that’s just silly hippy stuff. Your children and grandchildren will be fine.

A decade and a half before his “dirigible of drivel” quip, Alexander Cockburn wrote a column called, “Where’s the Left’s Reply to Limbaugh?” In it, he noted dedicated fact-checkers’ attempts to listen to the endless hours of Limbaugh’s show and correct all the lies. When Limbaugh said, “It has not been proven that nicotine is addictive, and the same with causing emphysema and other diseases,” the fact-checkers responded by pointing to a 618-page report by the Surgeon General.

Cockburn knew that this would have little effect. He remembered Ronald Reagan’s never-ending trail of lies about welfare queens driving Cadillacs. “[D]emagogues,” Cockburn concluded, “aren’t done in by careful itemization of error. They fizzle out because people weary of the act or because the political equation changes or because they face a real political challenge.”

He suggested a more productive strategy: zeroing in on the fact that Limbaugh claimed to be speaking for “the ordinary Joe” as he was “singing hymns to the innocence of the tobacco companies and assuring the small-business people that the Reagan tide lifted them in the ‘80s along with the super-rich.”

The world without rush

Now that Limbaugh has refuted his own “hymns to the innocence of the tobacco companies” by dying of lung cancer, some on the left might feel inclined to celebrate. The odious old hypocritical bigot is gone!

After a year of far too much death, that kind of thing might seem a bit distasteful even to many of us who loathed everything Limbaugh stood for. And it’s not as if Limbaugh’s passing is some sort of political victory. The corporate overlords who own all those AM radio stations won’t be giving Limbaugh’s old time slot to Ana Kasparian. They’ll find some new reactionary cretin to replace him.

What I am prepared to celebrate are the many signs that, in the years since Cockburn wrote that column, the political equation has started to change. Bernie Sanders’s runs for president, the election of “the Squad” to Congress, and the explosive rise of the Democratic Socialists of America have all conspired to make it a little harder to pretend to be all about “the ordinary Joe” even while conspiring to deny Joe health care. And the rise of new media sources like Chapo Trap House, where the hosts are at least as irreverent as Limbaugh ever was, has made the “socialist utopians” seem a lot more fun.

The equation is still changing at an agonisingly slow rate. The climate crisis Limbaugh spent his life minimizing looms over us, and the economic inequality he devoted so much of his career to rationalising is out of control. But maybe, just maybe, we’re finally getting a little bit closer to achieving a world where Limbaugh’s ideas are as dead as he is.

This article first appeared on Jacobin. Read the original here.

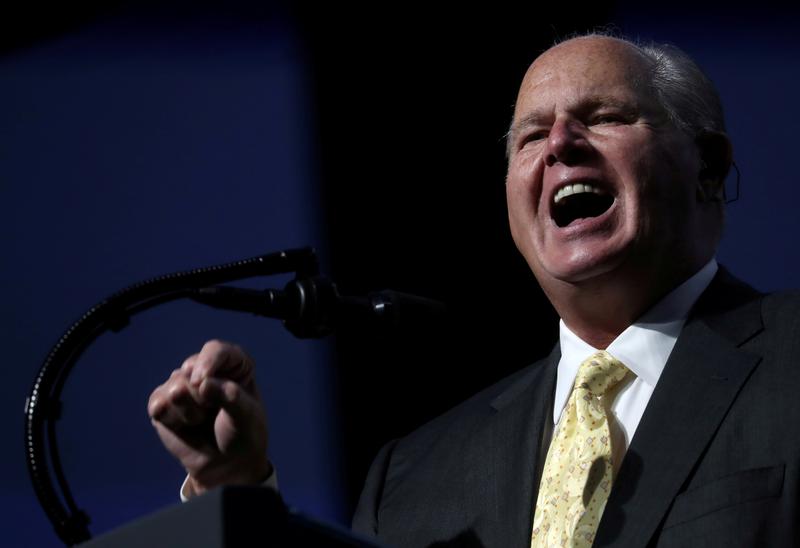

Featured image credit: Reuters