A new Apple TV+ psychological thriller, Sharper, opens like a romcom. Its first chapter – “Tom” – introduces a shy young man, Tom (Justice Smith), the owner of a bookstore in New York. One day, he meets a woman, Sandra (Briana Middleton), in his shop. They discuss books, unhappy families, unfulfilled dreams. They banter, make love, fall for each other. Director Benjamin Caron hits all the right notes: soft light, breezy pace, engaging cuts. A small sequence features snatches of dialogues intercut with quick visuals, relaying the momentum and energy of Tom and Sandra’s relationship. In less than 15 minutes, I was hooked.

But this section’s true ingenuity lies somewhere else. Before watching Sharper, I only knew its genre – nothing about the story. So I looked for ‘clues’. Surely, it can’t be this pleasant, I told myself. And I found an opening when Tom’s friend asks Sandra about her college. She replies “Vassar” but declines to divulge anything else, saying she spent most of her time in the library. Ah, a lie, I thought, maybe she’s projecting an image. But aren’t some love stories also (unintentional) con games – we fall for people who, after the ‘honeymoon phase’, reveal their true dark selves? Tom finds out that loan sharks are hounding Sandra’s brother. They want $350,000. The son of a business baron, Tom gives the money to Sandra. She disappears. Wait – who is she?

Chapter two: “Sandra”. This pattern persists throughout Sharper. Each chapter, a short story. Each chapter, a new character. Each chapter, a new con. We meet the real Sandra here. A parolee with a long criminal record, she encounters Max (Sebastian Stan), an enigmatic man who gives her a new identity (including the Vassar college cred) and teaches her the fine art of conning strangers. It’s how she meets Tom as well. But as the story deepens and widens, it also flings more questions: Who is Max? What’s his background, his story? As you wrestle with them, Sharper dangles a new carrot – one that, just like the last two chapters, will both satiate and tease.

Chapter three: “Max”. We’ve seen different variants of movies like these, where the makers always outpace the audiences – a twist hides a twist, a con hides a con, and betrayals unleash a domino- and boomerang-like effect. Such thrillers also run the risk of being overcrowded and flashy, as if fixated on flaunting their smarts. But Sharper’s storytelling has a relaxed and inviting quality to it. It’s also remarkably simple: We follow one character, solve one puzzle, and so on. We realise much later that this enterprise is inherently laced with deception — that this film, just like its characters, weaponises its seeming simplicity to con us.

Writers Brian Gatewood and Alessandro Tanaka also ace the timings of the twists. Even though the chapters keep getting longer – the first three clock 20, 25, and 29 minutes – they barely press their presence on us. The moment we start to get comfortable, the movie fires a new twist. Unlike many thrillers whose broad contours are clear, Sharper’s plot turns complicate the existing story and opens (literal) new chapters. How do you outsmart a film when you don’t even know what it’s about?

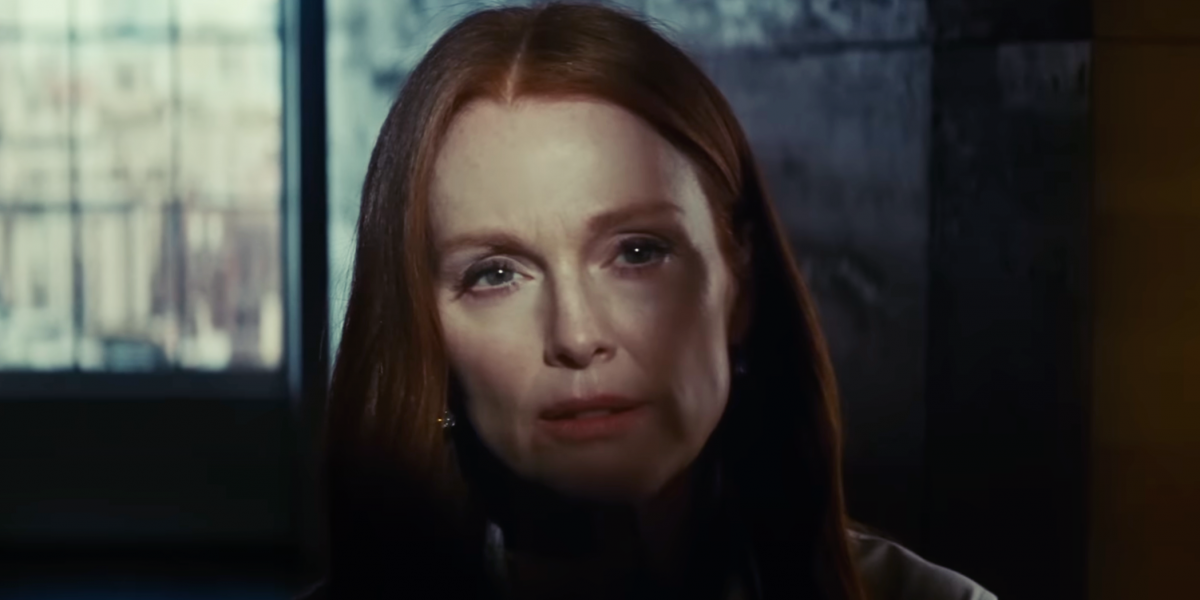

Besides Max, the movie hides another pivotal character, Madeline (Julianne Moore) – his “mother”. (I’ll say no more, even though none of these are spoilers; they all happen within the first hour in this 116-minute film.) As we find out more about Max and Madeline, she starts to dominate the movie which, again just at the right time, cuts to the next chapter titled, yeah, “Madeline”. If these characters intrigue us, then their portrayals sharpen the edge (Smith is especially striking), plunging us in a sea of constant questions. It took me a long time to unlock that this story isn’t a straight line as much as a circle, mirroring its characters’ deceptive circularity.

Sharper may not be ‘highbrow’ filmmaking, but it’s very clear-eyed about its ends and means. Its climax, for example, features a gun that contradicts its tone, as this movie is way too smooth for violent showdowns. I considered it a rare slip-up – maybe a climax-induced screenwriting anxiety – but its final chapter resolves that confusion, presenting a film very much in control. And like its characters, I realised later how seamlessly I was gamed.

This article was first published on The Wire.