Visiting Ahmedabad for me has always been a pilgrimage of sorts. I confess I must first visit Sabarmati ashram and have a spiritual conversation with Bapu. Then I wander around imagining the souls that once inhabited the Sabarmati ashram and wonder what we are doing with our foundational values and heritage.

This is always followed by a visit to the ‘Toy House’, the home of Ela Bhatt (1933-22) who passed away in November last year. This time, I planned to go to her home to pay my condolences to her family who kindly said they would send a vehicle to my lodgings. I got a call from reception and went down where I saw an autorickshaw that was different from the usual ones – it was coloured black. “This is Elaben’s rickshaw and I am her driver,” I was informed by Pradeep bhai, who further told me that for over 20 years, Elaben travelled only in this rickshaw to all her meetings. I was touched by the practice of simplicity as I am used to people flaunting their diamonds, cars and ostentatious lifestyle in Delhi.

Then I went on to Shanti Sadan – a large, ornate building that used to be the residence of Ansuyaben Sarabhai (1885-1972) and now houses a private museum run by the Sarabhai family on ‘Motaben’, as she is widely known. The chowkidar recognised it to be Elaben’s autorickshaw and welcomed me saying, “Woh hamesha isme aati thee” – she always came in this!

‘The Changemakers’

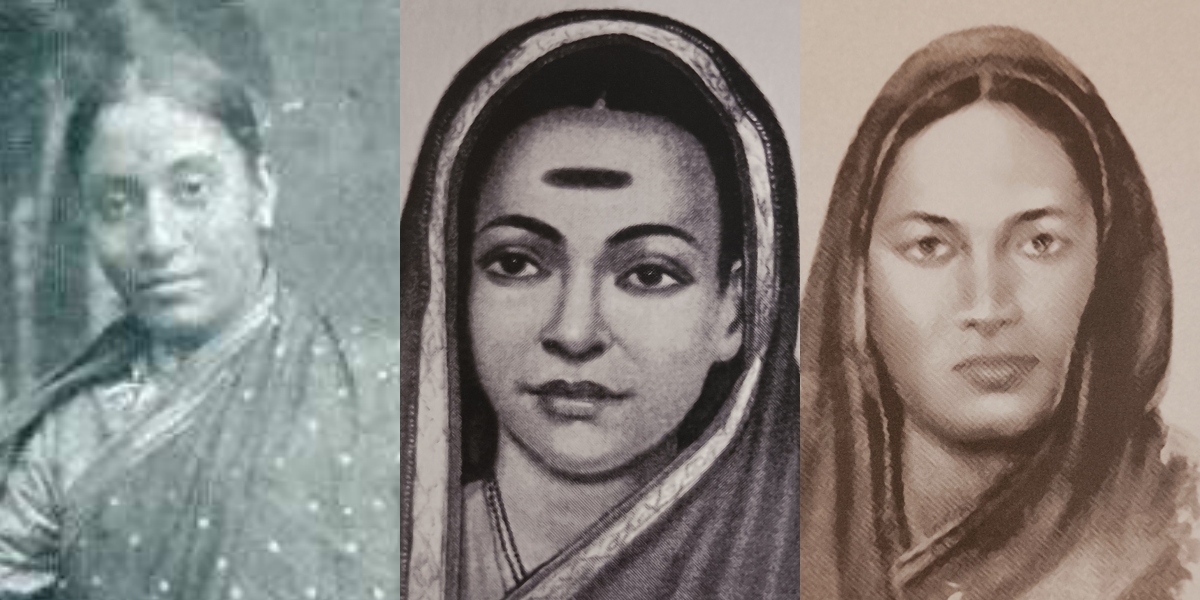

I had come to see an exhibition, ‘The Changemakers’ (on view till April 10) on women of the Bombay Presidency of the past. That was a time when girls were not even allowed to go to school, when the age of marriage was under 9, but there were still some women who valiantly strove to usher in change. Curated by Neeta Premchand, the exhibition – brought to Ahmedabad by the Asopalav Nidhi – is about the women who strove to make a difference despite all odds and is profusely illustrated with photographs, commentary and artefacts of the time.

By 1850, both Savitribai Phule (1831-1897) and Jyotiba Phule (1827-1890) had started schools for girls and people from lower castes but they went a step further and established the Satyashodhak Samaj which would enable the lower castes to perform the rituals of birth, marriage and death. This enraged both the Brahmins and the patriarchal society and they were expelled from their family. They were given shelter by Usman Shaikh. Here, they were also associated with Fatima Shaikh (1831-1900), who is considered the first Muslim woman teacher in India. It was wonderful to see their photos together and to know of the interfaith solidarity and feminist sisterhood that took place over a hundred years ago!

The circle of change continued with Rebecca Reuben (1889-1957) who studied at the Hazurpaga school started by Savitribai Phule. She trained to be a teacher in England and came back to teach becoming the headmistress of the Teachers’ Training College in Poona. From there, she moved to serve members of her Jewish community and was the principal of the Israelite school of Bene Israeli children. Her interest in education was wide-ranging and she was committed to bridging both Hebrew and Hindu cultures and was part of a new generation of women who chose to remain single and live simple lives dedicated to social and national causes.

Rebecca Reuben. Photo: Fred Csasznik/Jewish National Fund, Public Domain

Here is Rukhmabai Raut (1864-1955) who was married at the age of 11 and refused to go to her husband’s home as the marriage was without her consent. She became a doctor and was appointed the chief medical officer in Surat. She also went on to successfully fight for the age of marriage to be raised. Many of these women were encouraged by progressive fathers or husbands or, as in Rukhmabai’s case, her stepfather.

Rukhmabai Raut. Photo: Unknown author/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

Anandibai Joshi (1865-1887) had a rough start at home and a very early marriage, but it was her determination that led her to become a doctor, with a degree from the University of Pennsylvania. However, she returned to India only to succumb to pleurisy. But her life certainly created an awareness of the real need for women doctors.

Anandibai Joshi. Photo: Dall, Caroline Wells Healey/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

Pandita Ramabai (1858-1922) was born to a family of wandering scholars and was orphaned young. She walked across the country to observe how women were treated in Calcutta. Horrified by what she witnessed, she set up the Sharada Sadan for widows. She earned the title of Pandita through her own scholarship and knowledge of the Puranas. However, disillusioned by Hinduism and its strict caste system, Pandita Ramabai converted to Christianity – and was considered a rebel. Yet she kept the courage of her convictions and is counted as one of India’s earliest social reformers. Of particular interest is the ‘Letters and Correspondence of Pandita Ramabai’, as we so rarely see writings of the women themselves from those times. Also on display are several monographs and books on the earliest women reformers of our time.

Pandita Ramabai. Photo: Ramabai Sarasvati, Pandita, Press of the J. B. Rodgers Printing Co, Public Domain

Bai Motlibai Wadia (1811-1897) was the only one of 19 children to live. Apart from survival instincts, she had a natural flair for business and emerged as a philanthropist. She established the Bai Motlibai Obstetric Hospital because many women died for the lack of a female doctor, not wanting a male doctor to examine their bodies. She also gave land and money to the J.N. Petit Parsee Boys’ Orphanage.

Durgabai Deshmukh (1909-1981) was a freedom fighter who was imprisoned three times by the British and who participated in the salt satyagraha activities, addressing women in burkhas to come out. She became a feisty lawyer and a champion for freedom and women’s rights. She founded the Andhra Mahila Sabha in 1937 and is known as the ‘mother of social work’. She was a member of the Constituent Assembly and there is even a postage stamp issued in her honour. However, what is less known about her is that she walked out of a marriage at age 15 and later married C.D. Deshmukh.

Durgabai Deshmukh. Photo: By arrangement

Hansa Mehta (1897-1995) was born in a prosperous family and educated in England. She was strongly influenced by Sarojini Naidu and later by Gandhiji. She was one of the few women who was a member of the Constituent Committee to draft the Constitution and advocated justice and equality for women.

But the one whose house the exhibition stands, who came from an affluent family, was no less remarkable. Anasuya Sarabhai (1885-1972) who Elaben worked with, left her early marriage, went to England to study to be a doctor but found she could not bear to dissect cadavers and the sight of blood made her faint. She then moved to the London School of Economics, where she got influenced by Bernard Shaw’s lectures on socialism.

Returning to Ahmedabad, she launched the first strike for mill workers (1918) demanding a raise of pay – the mill was owned by her brother, Ambalal Sarabhai. While the credit for this strike has historically gone to Gandhi, a short documentary puts the matter in perspective. Elaben, in her last interview, is shown as saying: “Gandhi benefited from Anasuyaben. Anasuyaben started the strike but he joined it one and a half months later.” She also claims that Anasuyaben while opposing her brother, Ambalal Sarabhai, would later personally serve him food in the evening and this contributed to “Gandhi’s understanding of satyagraha”. Some food for thought here, as women are always marginalised from receiving their due share of the credit.

Anasuya Sarabhai. Photo: Sarabhai Archives, Fair use

Many of these women could have led comfortable lives, but they emerged and extended themselves for the cause of other women. While in Europe and the US, women were fighting for the right to vote and property, here the oppression was double-fold; women were shamed both by colonialism and the deeply entrenched patriarchal norms of the time.

A footnote: The receptionist where I stayed asked me to take the ‘autorickshaw from the back’ because many genteel places do not allow auto-rickshaws. When it comes to social reform, we have a long way to go, but I cherished the fact that I rode Elaben’s autorickshaw – one of the most influential changemakers of independent India who started SEWA, an organisation which now has 2.5 million members – to view the pathbreaking work of the women changemakers of the last century.

This article was first published on The Wire.