The act of tying a turban is formative to being a Sikh man for many, or rather feeling like a Sikh. For all the associations that have come with it – parodied or otherwise, the value of identity has never been a problem for most Sikh boys. Although, I have over the years observed many of my peers crumble under the pressure of being different and give up what I believe, beyond identity, is a unique perspective on life.

As we grow up we realise that every movement – political, cultural, or social, is birthed by the need for self-identification or determination. Akin to feminists or racial revolutionists who wish to live beyond stereotypes or predefined societal roles, Sikhs live the struggle for their acceptance each day as well.

As a young Sikh boy, identity and subsequent identification are lessons imbibed early on. Our unique identity with our bun of hair atop our head tied together in a (generally) colourful dastaar (mini-turban) garners much attention. Shockingly, we learn that our visual difference from most around us irks them. We become the butt of jokes, ridicule and at times harassment – all due to possession of unshorn hair. As a young person going through their developmental cycles, being different is often the last thing we want to be. Instead, we often hope to fade into the background. It’s almost a dawning realisation that the choice to wear an invisibility cloak does not exist for turbaned Sikhs (and interestingly, that is exactly the reason why we were given such an identity).

A late-teen or adulthood conundrum for young boys like myself is unearthed when they learn that their possible paramour is interested or attracted to a model with well-styled hair, many a time citing them as the pinnacle of visual attraction. At times informing us boys with colourful turbans of how odd we looked. The reality of societal conditioning is understood by a Sikh boy in the form of their rejection by most of their peers and paramours due to the way they look. Most young boys find themselves in a state of limbo, almost unsure of what this endless identification shall make for in their future. Interestingly, this is also the time when we start growing our beards, which most choose to live with unshorn. It takes a couple of years to settle into our adult aesthetic – bearded and turbanned.

Some of us spend these transitional years brushing our yet to grow beards, carefully taking care of the rare 15 hairs in our goatee. We desperately awaited the time when we could adorn our turbans with perfection and showcase our well set beards. Perfecting our turban style and tying technique could be the result of a few months on continuous effort. And if you’ve made it thus far as a man with a Sikh identity, you now shall enjoy the perks of standing out.

It is worth noting that the genesis of the Sikh turban is dual in nature. The socio-political origin generally referenced is Guru Gobind’s attempt to elevate every turbaned individual to the status of a king or leader, hitherto shattering the hierarchy of obeisance to any human form. We must note the context of the 16th century when only maharajas and such royalty were allowed to adorn turbans. The Mughals also forbade anyone other than their leaders and warriors from wearing turbans. These regulations proved to be the exact kind of oppression Sikhs became famous for overpowering.

The other origin lies in pure pragmatism, to enable upkeep of their unshorn hair. This allowed the identification of Sikhs at large among a group of people, cementing their role as responsible members of society.

It may give us a great deal of comfort in knowing that a turbaned Sikh symbolically carries upon their head the crown of overthrowing the oppressors. This is a universal lesson to each individual beyond religious stratifications. When we look upon the head of a Sikh, it is a philosophical reminder of inquilab and fateh.

Each individual who adorns a turban has his or her own unique experiences with it. They have their own routine and process to get to their best turban outcomes. They have their favourite colours, favourite occasions and favourite moments (which generally happen when complimented).

Also read: An Open Letter to Everyone Who Thinks I Have to ‘Look’ Sikh to Be Sikh

On most days, tying a turban is a cathartic process. It allows us some sahaj (patience or composure), this entire process of tying and adorning a turban leaves us with a sense of fulfilment. Some days we feel like artists, who practice their art perpetually. Alternatively there are also bad turban days, similar to bad hair days. On these days we just cannot get the cloth under control. It takes forever to put together a well-tied turban, we frustrate ourselves to the point of not leaving home. We surrender our sahaj and find ourselves disgruntled.

That being said, I think it’s integral to understanding the phases of turban tying to learn more about what it means to tie and express through it. Most turbans range between 4-7 metres. I personally tie about four metres.

The selection

Turban colour choice varies from person to person with some people using the medium of their turban to bring colour into their life. Some match their clothing with the colour of their turbans or ties. Some of us prefer the duller blues and blacks unless we feel festive. Regardless, the choice reflects much of our personality and preference – a clear visual indicator of our inner selves. In this essay, I am wearing a charcoal coloured turban from Singh Styled.

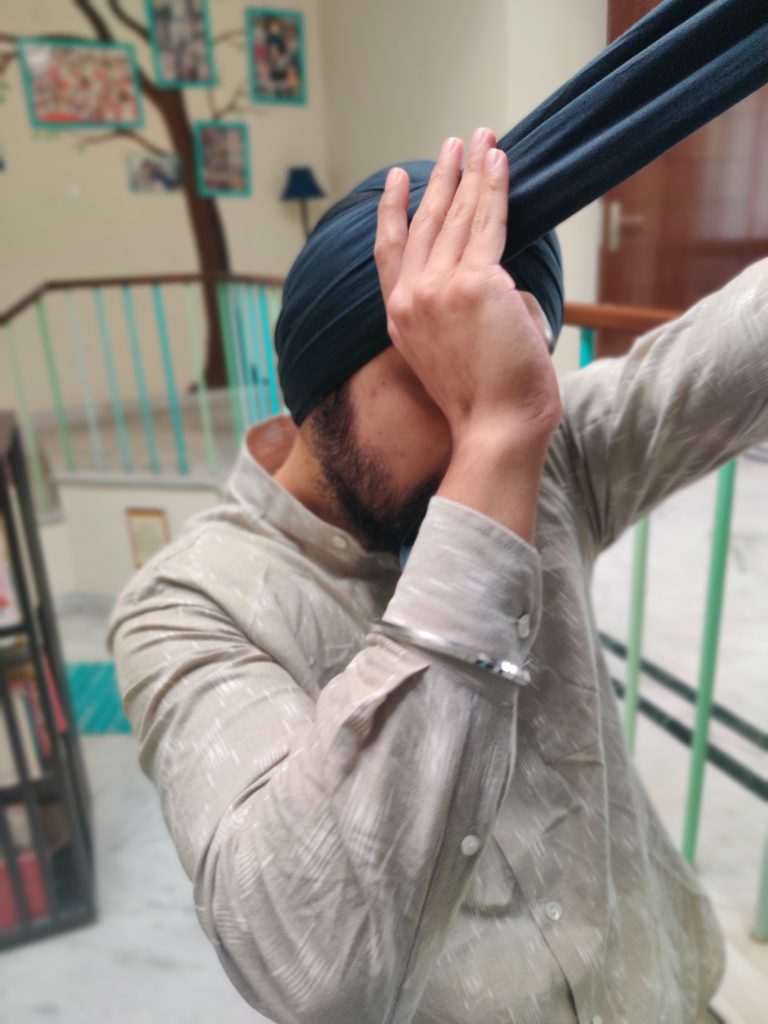

The preparation – pooni

The pooni (or folding) is an important part of the process. While it may take just about two-three minutes to complete. It is a technique perfected only over time. It almost always has its visual impact on the final turban when done perfectly (or otherwise). As seen through the photo, the folding can be done with a partner or individually using a door knob or a window frame. Most Sikhs evaluate hotel rooms and spaces based on their ability to stretch out their long turbans (sometimes 6-7 metres long) and a bracing point with great structural integrity.

On a lighter note, in the Punjabi movie Jatt & Juliet, the protagonist, actor, Diljit Dosanjh asks an air hostess when their arrival is announced for her help in doing the pooni. That hits the spot of the sentiment underlying this phase perfectly.

The lighting

Turban tying is as much about lighting as it is about tying. The wrong lighting can severely impact the outcome desired. Sikhs (mostly men) have a great sense of overhead lighting and their requirements. Funnily, after a point, we develop enough dexterity to tie a turban without a mirror altogether.

The positioning

The way the first wrap or ladh is placed sets the tone for the tying engagement. Some of us take up to two-three minutes just here. It needs to feel intuitively right. The placement is a task of intense focus to ensure an easier and more enjoyable tying experience. We brace one end of our turban tightly between our teeth.

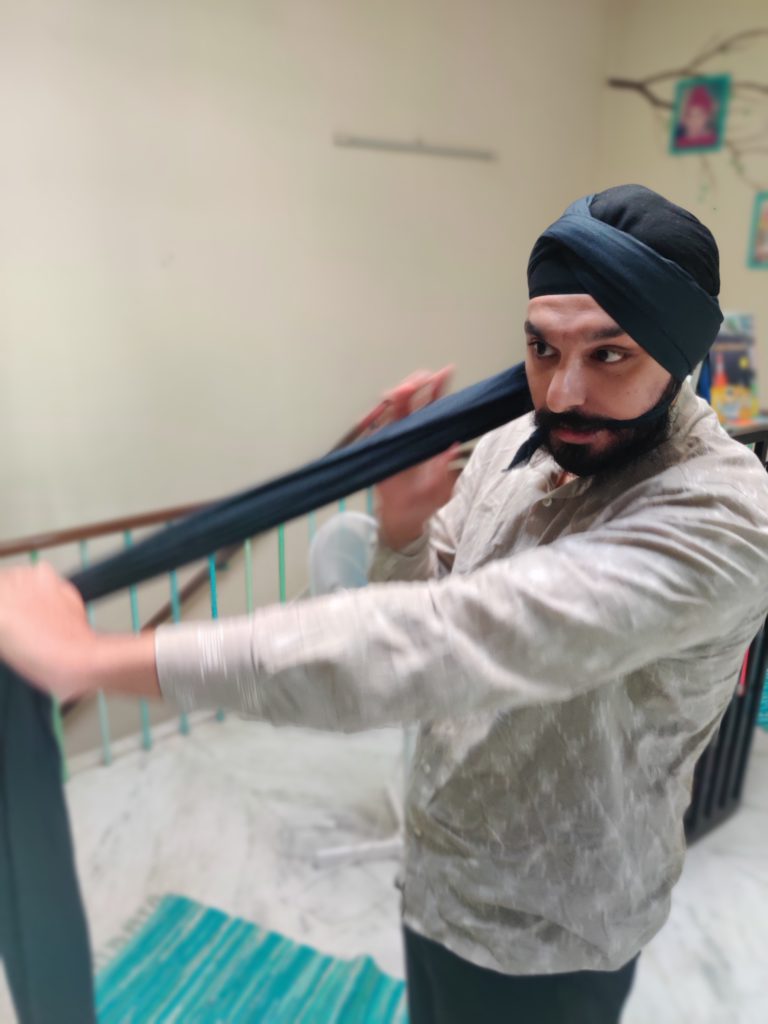

The wrap – ladh

The pooni kicks into hyperdrive now and plays an integral role in the quality of ladhs or wraps. Most Sikhs depending on technique go up to five or six ladhs regardless of length. Each placement of the wrap is where the artistry lies. These wraps must be seamless and minimal with absolutely no ripples or infolds. The distance between each ladh is targeted to be equidistant. The angle of placement is associated with the style or expanse of tying style. Any ripples lead to frustration. Yet, we must stay in chardi kala (motivated spirits). One cannot help but smile when the ladhs fall perfectly and cleanly, almost a sense of achievement every time one manages the same. The entire process is almost art-like, cathartic and fulfilling.

Many times we wonder how would anyone care if our turban is not tied well, most non-Sikhs would not be able to make out the difference. One can live in this myth till a friend or colleague points out a poorly tied turban to you on one of your bad turban days.

The finishing

As we approach the finishing stage and admire the well-tied turban adorning our heads, we can’t help but feel supremely confident about our chances of acing the day. The metaphysical impact of the turban is such. It feels almost like a part of us. A symbol of our perseverance against oppression, a promise to be responsible citizens of society, and to uphold values that are one with nature and nurture.

To share some concluding thoughts, this essay on turban tying hopes to encapsulate many feelings and phases – both good and bad, lending a certain honesty to our Sikh existence. There have been moments when the going has been tough, the rejection and racism have been bad. Yet we hold true in ourselves the resolve that no matter what, each and every unique identity in the world deserves respect, including ours.

Diversity is colourful, just like our turbans.

Arshdeep Singh runs a branding and design studio called Kwa:zi and spends most of his time building brands for his clients. A keen observer of human behaviour, he has a deep interest in the socio-political manifestations of society.

This article first appeared on The Sikh. You can read the original here.