For most of the last year, I was stuck in limbo between school and college with even less to occupy my time than most people. Without even the routine of online classes or work to keep me busy, I spent my time half-consciously watching 30-second videos and refreshing the Google COVID-19 tracker.

But every once in a while, I tried to find beauty in the routines of my socially-distanced life – I took the time to savour my morning cup of coffee, even though it came from a jar of Nescafe Instant instead of a french press, and spent a few minutes sitting on my balcony, listening to the chittering of the two navy-and-red birds that had taken up residence on the ledge.

In other words, I tried to live my life as if I were in a Studio Ghibli film.

There’s a lot to be admired about Hayao Miyazaki and his creations: the painstakingly hand-drawn animation, the fantastical storylines, the young heroines who were strong-willed and free-spirited decades before Elsa sang ‘Let it Go’. But while watching and re-watching the animated films in the past several months, I’ve found myself less enthralled by the magical adventures and mythic landscapes and creatures in these films than, as Miyazaki himself describes them, by the silence between his claps.

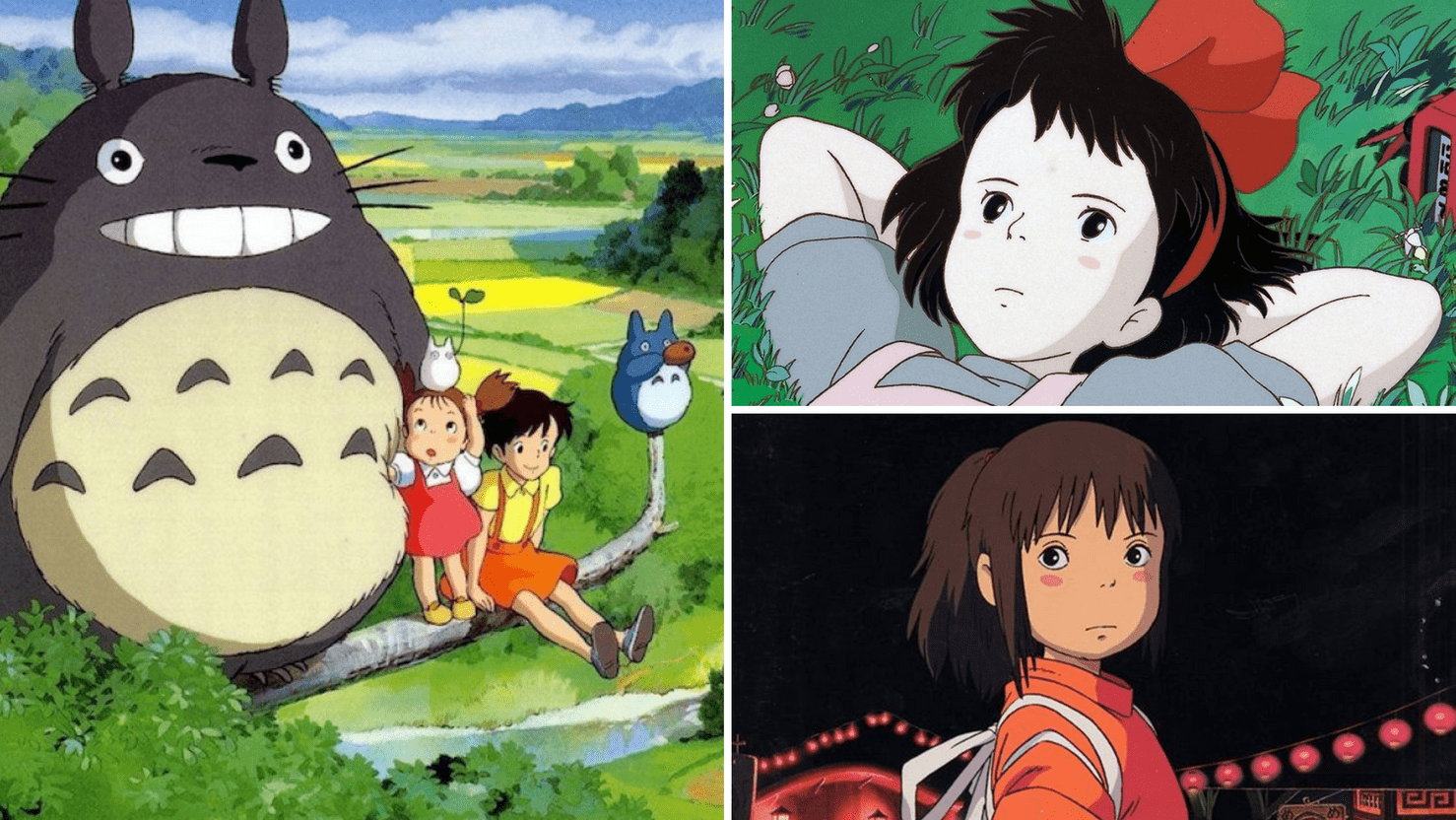

These moments of quiet, ubiquitous to Japanese art, are called ma. Whether in films that meander along without an overarching conflict, like My Neighbour Totoro or in epic fantasies like Princess Mononoke, this concept of negative space, literally translated as “gap” or “pause”, gives Studio Ghibli movies their signature sense of immersive realism.

A still from ‘My Neighbour Totoro’ (1988)

One of my favourite scenes from the studio is such a moment in Ponyo, an adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid. After a treacherous drive along the edge of a cliff during a tsunami, Lisa makes her son Sosuke and his newly human companion Ponyo some honey tea and instant noodles with ham.

Also read: ‘Perfect Blue’: Relevance of a 1997 Anime Film in Today’s ‘Real’ World

The visuals of the scene are exquisite, with glistening honey clinging to a spoon as it is swirled around in a mug and the copious amounts of steam rising from the bowls of ramen giving the whole thing a warm, hazy quality. But it’s the kids’ childlike happiness – Ponyo’s fascination with “haaam!” and Sosuke’s satisfaction at teaching her how to eat and drink – that makes it so memorable even though not very much happens in it at all.

A still from ‘Ponyo’ (2014).

This isn’t to say that Miyazaki’s quiet moments aren’t full of movement – they are. The films are filled with constant, almost gratuitous motion. In Spirited Away’s supernatural bathhouse, kami (spirit) guests feast and bathe and socialise in spectacles of excess. Yet alongside them, both the human and non-human bathhouse employees go about their days just like the working class in any other remote little town in our world – they spend hours at their repetitive jobs, cleaning, waitressing, feeding the furnace; in their moments of respite, they relish simple foods and plan to move to the big city one day.

Breaking several ‘rules’ of Western storytelling, these moments don’t do anything to further the plot of the movie. But without them, the world of the spirits would seem far shallower, and the pervasive feeling that this world was not really so alien to us would be lost.

A still from ‘Spirited Away’ (2001).

Most of the films centre around and are geared towards children. But this is a strength, not a weakness – to Miyazaki, what makes kids the perfect medium through which we explore his worlds is that they have not “had their childhood violated by adult common sense”.

In My Neighbour Totoro, the Kusakabe sisters, Satsuki and Mei embrace every part of their new village home, from the old, creaking cottage to the various kami that inhabit the countryside. In the movie’s most iconic sequence, Totoro and the sisters are both waiting at a bus stop in the middle of a downpour and Satsuki offers him (her? it?) an umbrella. Totoro, after figuring out how an umbrella works, happily accepts it and is so fascinated by the plip-plop of large drops of water falling onto it from a tree that he jumps and makes all the water on the branches come crashing down on them. After enjoying the consequences of his mischief, he gifts the sisters a pouch of ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’-esque magical seeds and speeds off in a yowling bus-shaped cat with headlights for eyes.

It’s the sisters’ combination of fierce independence and youthful sense of wonder and trust that allows them, and consequently us, to see Totoro as something in between a large, cuddly teddy bear and a protector-god and jump into his strange world with only the slightest hesitance.

You can watch Kiki’s Delivery Service for its surprisingly mature depiction of creative burnout and loneliness or just her sardonic but lovable cat, and Laputa for its powerful messages on capitalism and technology or its sweet portrait of the very ordinary family life of some extraordinary airborne pirates.

But either way, Studio Ghibli’s ability to make the everyday just as magical as the unimaginable will make you see the world around you just a bit differently, even (especially) if that world is limited to your living room.

Shriya Ganguly is an English literature student with an interest in absolutely everything except professional sports.