Some answers take time. Some words bleed their way onto the paper. Sometimes, much more difficult than the pain is the act of registering it. My apologies for being late – very late, as some might say – in sharing what I am about to. But I would still want to answer the administration of the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay, which declared “discrimination by students, if at all it occurs, is an exception” while refuting charges of institutional failure to create safe spaces levelled by the Ambedkar Periyar Phule Study Circle (APPSC) after an 18-year-old Dalit student, Darshan Solanki, allegedly died by suicide.

Dear Darshan, when I read about you, I asked myself, “What if I had raised my voice when I was in college? Would things have been different for you?” I don’t know. But I am sorry and I understand you. I may not have any answers today. But to you, I promise, I will keep raising questions. Until a fine morning when, as Rohith Vemula would say, “our birth ceases to be our fatal accident”.

Also read: Dalit Student’s Suicide Points to Well-Known – But Ignored – Caste Discrimination in IITs

Clutching at the feeble assurance from a dear friend – “Don’t worry. You don’t look like an SC/ST” – I trod carefully into my classroom. It was and still happens to be one of the premier engineering colleges in the country. A dream for many. Eyes searching for someone to call my own, fingers chafing each other in a hope to wear off the anxiety, steps tiptoeing to the feeling that I perhaps don’t belong there, I dragged myself to the third seat. We were made to fill out some forms. As I turned around to ask for Fevistick, the guy behind me peeped into the form to check my ‘Category’… He curled his lips. An unfriendly ‘smile’ which certified that I didn’t belong there. Something that would be written, rewritten, engraved and shamelessly branded on my fate in the days to come.

Life at the university would show me how marks, degrees, distinctions, awards and honours cannot teach you humility. Sadly, only education cannot build an egalitarian world. If it were so, there would be no oppression in the countries with the highest literacy rates. And an education devoid of political consciousness is even more dangerous, as it often enables and aggravates discrimination by handing over innovative ways to do so. People learn subtle and sophisticated ways to perpetuate the same discrimination. Like they say, ‘now in new exciting flavours’.

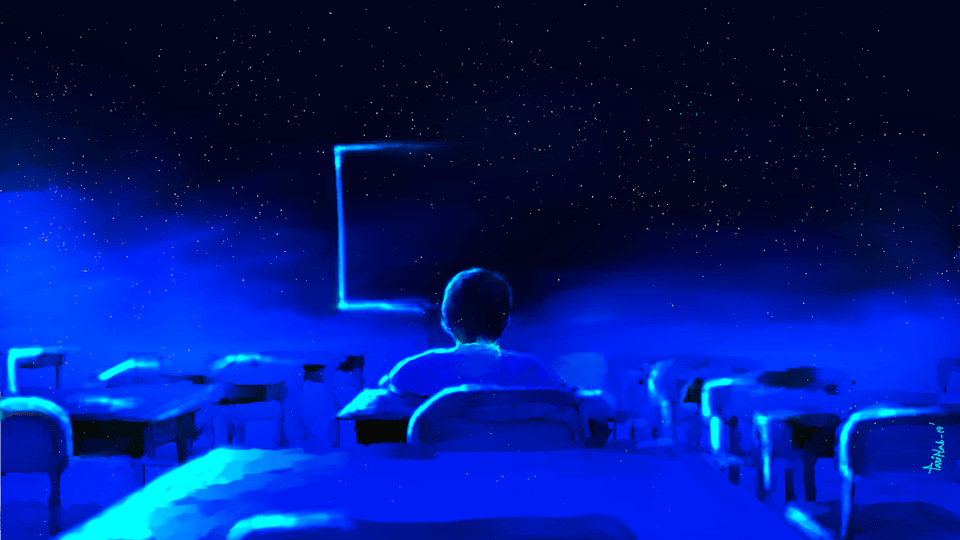

A few days into college and the classes had begun. It was the first class of Prof X, a prominent name in the Department of Mechanical Engineering. The hulk-like man entered the class and responded to the greetings with a quick nod and waving of hands. His first words were, “Everyone get up and introduce yourself. Your full names and your AIEEE ranks.” (AIEEE is the All India Engineering Entrance Examination, which was conducted in those days.)

A classroom. Photo: Pixabay

In the introduction that followed, all the names which weren’t ‘full’ to his understanding, were asked again. Like, “Neha” “What after Neha?” “Nothing? Ok!” And all the ranks after 50,000 were repeated loudly. Very much like an announcement. The students who were clearly uncomfortable disclosing their ranks in the class were sometimes shouted at to announce it loudly. With eyes feigning shock and a voice pumped with pride as if he had ‘uncovered’ some truth, Prof X used to say, “Say it loudly. One lakh??? Ooh.” The ‘introduction’ formally declared everyone’s ranks, hence also their ‘categories’, to the fellow classmates.

Remember? The new exciting flavours of caste discrimination: Upgraded. Neat. Subtle. Classy.

Eventually, over the next few weeks, we began following an unsaid decree. All the students from SC/ST/OBC categories began sitting together in the right-hand-side rows. Today, when I look back at it, it reminds me of how Dalit houses are always located at the periphery of the villages. The caste system likes to keep things neat. No mixing. My grandma used to say, “We have come far. Quite far. Away from those villages. Away from those shackles. Of the place where we had to carry a log in our hand and beat it against the wall to alert the upper castes of our presence.” She is no more. I wish I could ask her, “We might have left those shackles. But Dadi, have they really left us?” My father is a Class 1 gazetted officer in the government. But caste hasn’t left us. Poverty might have. But caste surely hasn’t.

Also read: Casteism Is Rampant in Higher Education Institutions, but Is ‘Wilfully Neglected’: Study

It was raining heavily. A few months into college life, we were all dressed up and had only two umbrellas. It was a fairly long walk from the department to the college gate so I asked a classmate if she could share her umbrella. She refused curtly and instead shared it with another girl. Confused at the behaviour, I chose to dismiss it for a misunderstanding. Later, we got into the Gramin Seva. I began feeling thirsty and I asked the same girl for water. I, perhaps, wanted an answer for the weird behaviour. Her bottle was full and she again refused, “I don’t share water.” Some weeks later, when the results of our first semester came and I scored higher than her, I heard her talking to another friend, “Astha got here from reservation. Itni bhi intelligent nahi hai. I can also get as many marks as her. I simply didn’t feel like studying this time.”

Throughout my college days, whenever I scored well, it never felt like an achievement. It was more like a due I had to clear. An acceptance I had to win. A ground I had to secure. More than happiness, it became a relief. A security blanket if you will. Before joining the college, I was told by my father, “There will be times when your merit will be questioned. Sometimes, when you enter with reservation, it becomes more important to prove your worth. It might mean working harder than general-category students and scoring much more than them. No one should be able to question your ability as an engineer.”

Today when I look back at it, I understand not just the futility of that advice, the miserable ‘need to prove your worth’ which used to nauseate me sometimes and the ‘questioning of merit’ which my father warned me about, it also lays bare what he must have gone through and might still be going through in his office. The fact that a progressive father who holds a coveted position and enjoys a privileged status still has to warn his daughter of the perils of being a Dalit.

Even today, he cannot afford to shield her from the shackles of caste. Times and places have changed. People and their ways have changed. But it’s the same old helplessness. Old. Rotten. Stinky. And unbearable. But still there. The same helplessness he must have felt in the eyes of his mother – who sometimes had to work as a seasonal labourer – when she used to carry him along to Brahmin households to ask for work. Too many miles away from those chains, he has walked a hard path from being the son of a labourer to a government officer. He, probably, never knew that all along his caste would be following him.

Colleges are often places where we find love. Fresh love which feels like spring. Young love which smells sweet. Those stupid grins and rosy dreams. Everything was film-like. You know, the way it is supposed to be. Until the guy who had peeped into my form told my partner, “You are seeing her? Bhai, vo to ‘quota-wali’ hai.’ (Quota – a word used for reservation). And smash. Everything shatters in a minute. All the castles turn to pointed shards on the floor.

Perhaps I have moved ahead of all those insults. Perhaps I still carry those wound-shaped voids. But I have come far. Have I?

Representational image. Photo: Khadija Yousaf/Unsplash, (CC BY-SA)

A few months ago, I happened to talk to one of my college friends. He got married recently. But not to his girlfriend from college. When I asked him what had happened, and why their long-term relationship didn’t work, his answer reopened those old wounds. They pierced into those old voids. “Yaar usse kaise karta shadi. Vo SC thi na. You know I am a Brahmin. Mai ye sab nahi manta. But still….Oh, by the way, tu bura mat manio ab.’(How could I have married her? She was an SC (Dalit). And you know, I am a Brahmin. I don’t believe in all this. But still….. Oh, by the way, you don’t feel offended now).” He was the same guy who had once said during a conversation on reservation, “There shouldn’t be any reservation. There is no caste system these days. It’s a thing of the past.”

I am a journalist now. And a profession that is supposed to stand with the oppressed should also have the representation of the oppressed in its newsrooms. But does it? We see no big names, no big Dalit editors barring a few. A few newsrooms, not from the mainstream media, have begun to focus on inclusivity and have embraced the policy of diversity across caste, gender and religion. The fact that an upper-caste journalist friend motivated me to write this story, kindles a little hope. When I see lines like, ‘We prefer candidates belonging to oppressed communities’ in a job description, it sprouts some faith. But we as a society need more. Much more.

Naive as it may seem, but like a hopeless romantic, sometimes against reality, I will continue to hope. I will continue to fight to be able to hope. Hope for a world where Darshan could be friends with anyone, where his caste will determine neither his fate nor his friendships, where Dr Payal Tadvi wouldn’t have died trying to prove her efficiency, where she wouldn’t have to write, “I can only see THE END.” A world where Rohith Vemula could fearlessly dream about the stars. Write about the stars. Where his value won’t be “reduced to his immediate identity”. Where a writer of science would not have been forced to write a suicide note.

To that world, we shall walk. In that world, we shall be.

Astha Savyasachi is a journalist based in New Delhi.

This article was first published on The Wire.