‘Hey You…’

‘Who, me?’

‘Yeah… Which formula should we use in the next step?’

‘Sir, formula… it is… I think… means…’

‘Why are you people given admission? Worthless creatures. Sit…Next…’

I wasn’t sure about the formula, nor did I know how to navigate that situation – which was no less than a compulsory visibility of an invisible vulnerability.

I can’t remember why I stayed silent. Was I actually unable to answer him? Or did I fear being judged by a room full of savarna students staring and giggling at me?

I’m not sure.

I clearly remember praying to become invisible, at least for a bit. I was dying to bury both my ‘lack of merit’ and ‘disputed’ body under the wooden desk haphazardly inscribed with some savarna fantasy of love with two names connected by an arrow inside a heart.

Years have passed since that incident, so why have I drudged it up now? What does it mean at a time when physical education, classroom bullying and exclusive discussions are being replaced with online education?

A few days ago, while going through articles on the negative implications of online education, I thought of the first few months of my time at a prestigious college in Kolkata, a place I had a tough time adjusting to because of my vernacular schooling.

I realised I didn’t quite have any memory of participating in classroom discussions, nor could I recall any group interaction where I fluently expressed myself in the language that was expected of me. I could only recall the humiliation, isolation, laughter, and above all – the indelible mark of visibility.

While the ongoing criticism of online education is pertinent in all its shapes and forms, it couldn’t address my fundamental query: how is a classroom lecture considered a universalised egalitarian form of imparting education?

Also read: The Tyranny of the ‘Normal’

The physical space of universities definitely provides space for students from different castes, genders, classes and communities. We get access to the library, join different social organisations and attend seminars. In short, despite the biases of a university space based on gender, class, caste and religion – some sort of equality is still there, which online education is largely bereft of.

However, the discussion around accessibility and infrastructural limitations of online education is much more complex than what meets the eye. A lot of students during Zoom sessions struggle to find a blank wall as a background to hide either the dust, mess or chaos visible behind or a photo frame of Sai Baba or another god, in order to portray a secular image of their families in front of their savarna liberal friends online.

The anxiety of self-representation in front of the selfie camera overtakes any other existing objective.

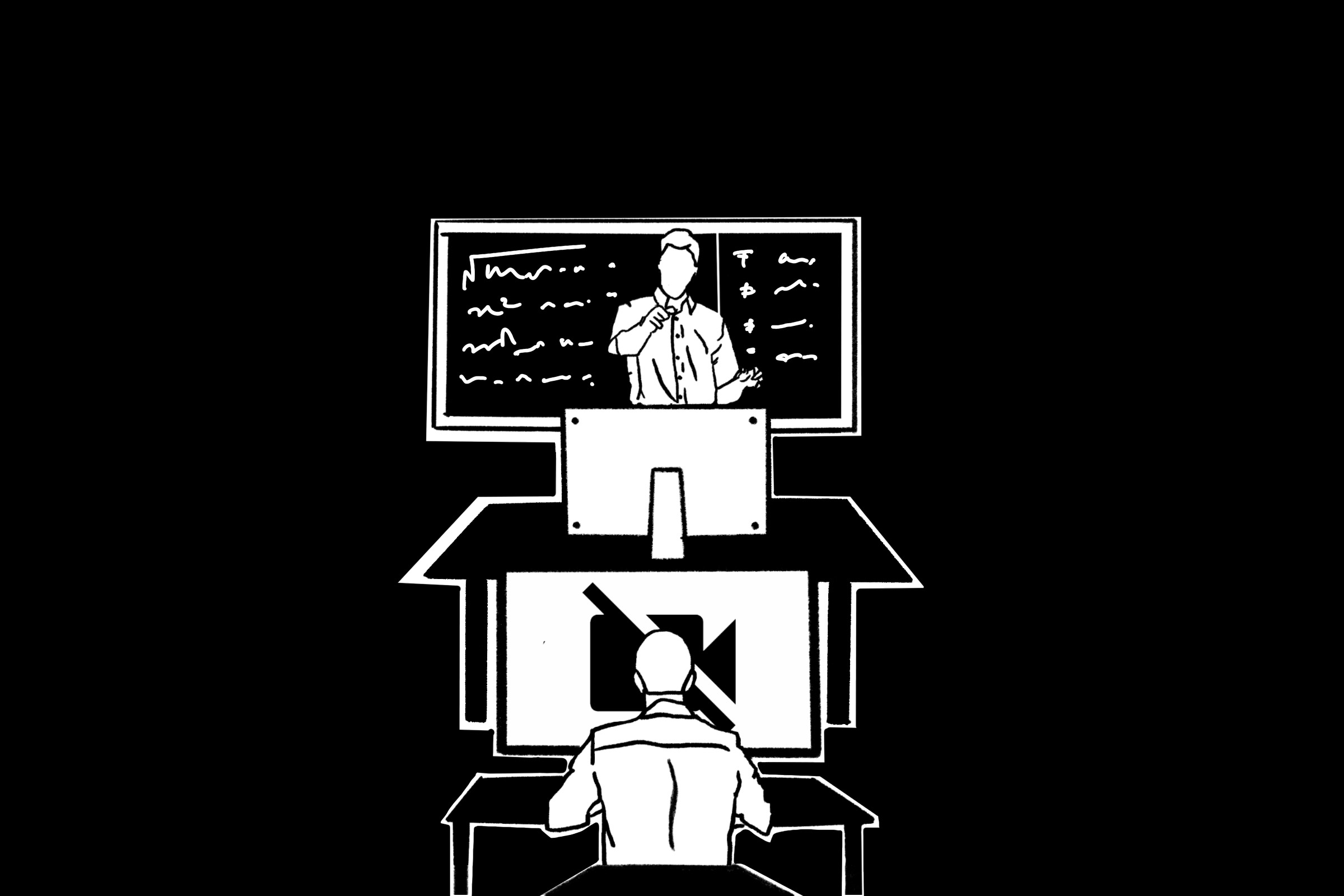

Thankfully, I found some relief in one of the key features of online mediums – the option to ‘switch off video’. Without knowing it, this is something I have been searching for my entire life since the bullying I endured at that elite college.

I ‘switch off video’ and my face isn’t visible anymore. If I get asked a question, I respond in the comments section. I don’t have to put up with laughter echoing in the background. I am not marked. I am invisible – a silent learner instead of a humiliated participant in an exclusive conversation.

Whenever online education is criticised – for all the right reasons – there is a universal assumption that students must interact and participate in class discussions, that they love to engage in group activities, that they are extremely fond of finding their own groups to script memorable memories.

Perhaps, what is missed are the students like me – who can’t communicate properly in English, owing to their vernacular schooling; who can’t make friends easily due to the lingual limitation and visible lack of savarna physical features’ who can’t be part of groups for lack of interest of others to include them or who chose not to have any friends or a ‘campus life’ than being bullied for having one.

For me, the screen of my mobile phone gave me a space to hide behind – a space to keep my self dignity.

I am not saying that online education is the best alternative. But while critiquing the online mode of education, aren’t we universalising a few assumptions about a students’ capacity to voluntarily participate in classroom discussions?

Are we deliberately sidestepping the caste-class-gender-religion biases of the physical classroom?

So, whenever we go back to the traditional mode of teaching, we must rethink why many students feel the need to ‘switch off video’.

Abhik Bhattacharya is a doctoral fellow at School of Liberal Studies, Ambedkar University, Delhi, and works on systematic exclusion and urban spatial segregation of Muslims in Jharkhand.

Featured image credit: Pariplab Chakraborty