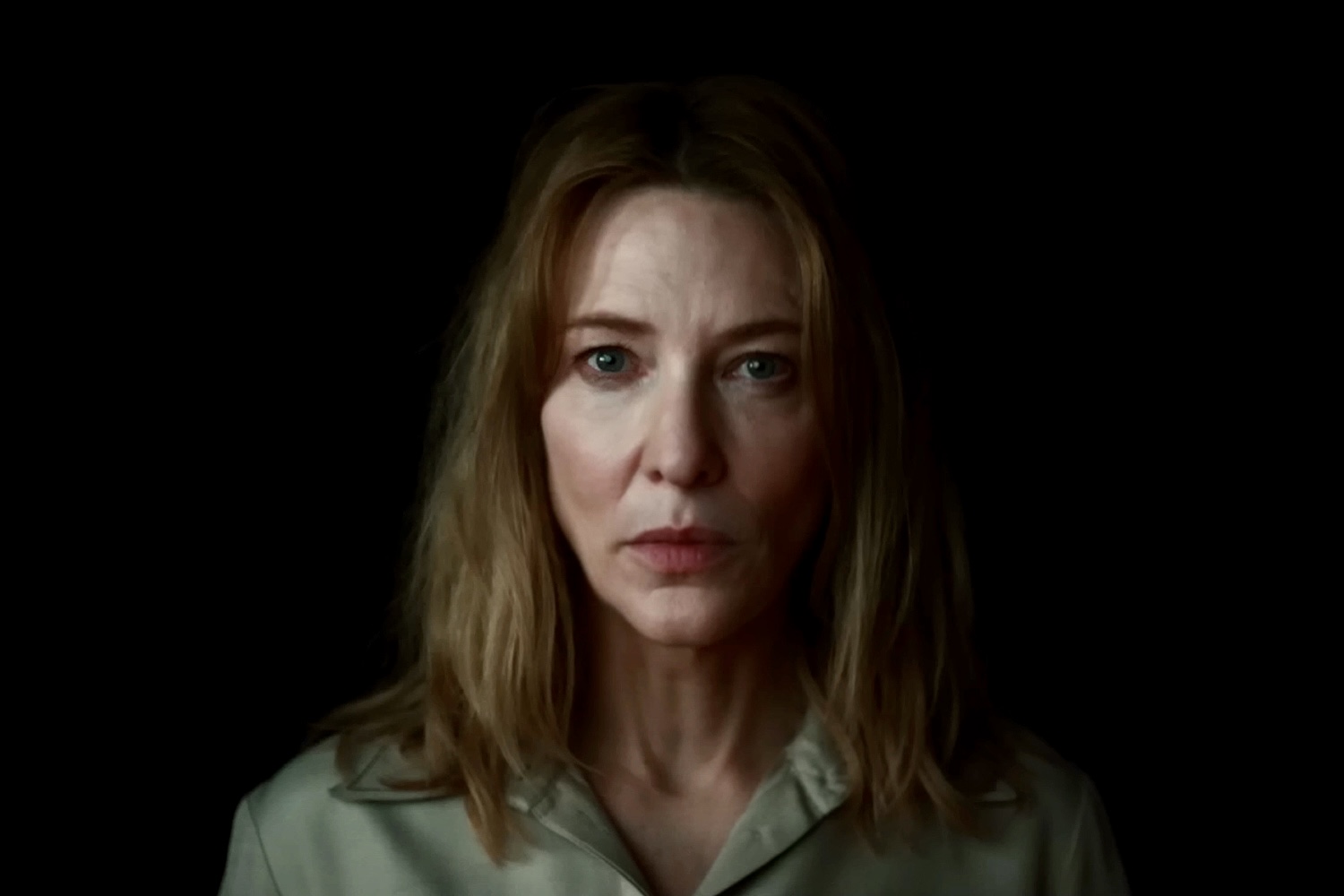

Tár follows a fictional all-powerful female orchestra conductor and her fall from the height of her career. Lydia Tár is portrayed as one of the top conductors in the world and the first female conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic.

The film aims to ask if gender matters when it comes to power. How does our judgment change when an abuser is female? What is the place of identity politics in art? Can art be separated from the artist?

To draw the audience into these questions, director Todd Field works hard to convince the audience that Tár and the classical music industry portrayed in the film is real. He does this by blurring the lines between the film and real-life people in the industry while also relying on most audience members’ lack of understanding of the day-to-day work of an orchestra.

The film slides between reality, mythology and fantasy in depicting an orchestra and a conductor’s powers.

Muddling fact and fiction

The film opens with Tár being interviewed by Adam Gopnik, a New Yorker writer, who plays himself. In this interview, a substantial number of her biographical details share striking parallels with those of the world’s actual leading female conductor, Marin Alsop. This muddle of fact and fiction left audience members believing that Tár was a real person.

Marin Alsop was understandably unhappy with the similarities. She also pointed out that Tár plays into a sort of “maestro mythology” where “real” conductors are untouchable geniuses with unparalleled musical skills.

A study conducted by neurology academic Seymour Levine and his son Robert Levine, a violist in the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, observed that underlying the behaviour of conductors and musicians in orchestras is:

the myth of the conductor as omniscient father (“maestro,” “maître”) and the musicians as children (“players”) who know nothing and require uninterrupted teaching and supervision.

They concluded that the “disparity between myth and reality in professional orchestras is extreme and serves as the most powerful source of musician stress and counterproductive institutional dynamics”.

This myth plays out in Tár where musicians respond with affable compliance to all her musical decisions, even those they’re unhappy or uncomfortable with. We’re led to believe that Lydia Tár is fully responsible for the final artistic product. The musicians are simply following her every gesture as a united body.

In reality, while what audiences see appears to be a carefully choreographed performance of shared intentions and performance goals, beneath the surface lies a web of competing influences and interactions in which the conductor may only play a small part.

Musical authority in performance

Analysing more than 1,500 comments from orchestral musicians describing who and what they were responding to in real-life rehearsals and performances, I have studied the process of artistic “authorship” in orchestras.

What I found is that opinions about how things should go differ dramatically throughout orchestras and that there is only one overarching shared goal in performance: to play together and to achieve ensemble cohesion.

To be clear, what constitutes ensemble cohesion at the highest level is complex and nuanced. To play together precisely in time, musicians must have a developed sense of every aspect of the sound, colour, volume and phrasing of their part. They must play with not after their colleagues.

To do this, they must make split-second decisions about what’s best for every note, drawing on their extensive musical experience while navigating the decisions of the musicians around them. They’re also often battling acoustic situations as they can only hear part of what the orchestra is doing from their seat. The conductor’s usefulness in this is extremely variable and partial.

One professional brass player explained to me that there was a visual knack that players have by watching each other. For example, the euphonium part in Holst’s Mars from The Planets the strings will play down bows. The brass player noted that some conductors will try to push the piece on there. If they were to follow the conductor there, they would be early. It was more helpful seeing a bank of strings all doing down bows, which let them know exactly where to place a note.

While in rehearsal a conductor can stop play and ask for a change, in a performance they can’t. This changes the power dynamics in ways some conductors might be uncomfortable admitting.

Systemic abuse

Research has shown that musicians in self-governing orchestras, such as the Berlin Philharmonic, have generally higher job satisfaction than colleagues in other orchestras and “that players in these orchestras are the real masters of their ensembles”.

However, the international classical music industry is steeped with systemic power imbalances and abuses.

It’s not just high-profile #MeToo cases in the upper echelons of the profession, like those of real conductors James Levine and Charles DuToit (both named in the film), on which Tár’s sadistic power trips are modelled. The body of evidence of abuse within musical institutions, from schools to professional orchestras in the UK, continues to grow.

A recent survey by the Independent Society for Musicians reported that 77% of respondents (rising to 88% of self-employed) did not report offences. The main reasons given were: “it’s just the culture” in the music sector (55%), followed by “no one to report to” (48%) and “fear of losing work” (45%).

While 72% of incidents were committed by people with seniority or influence over their career, 45% were committed by colleagues or co-workers and 27% by a third party (such as an audience member, client or customer). The report noted that 58% of the discriminatory experiences reported by respondents would be classed as sexual harassment.

By so masterfully interweaving reality and fantasy Field both affirms the harmful “maestro myth” and detracts from the actual, complex and deeply embedded webs of power abuse within the music industry today.

Cayenna Ponchione-Bailey, Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellow, University of Sheffield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.