Deepa Das, a mother of two, was one of thousands of women who were forced to face the overwhelming repercussions of the 2017 Assam floods after she and her two children were displaced from their home. In an article published by Women’s Media Centre, Das, who was seven months pregnant at the time, stated her apprehens

The Assam floods in May 2020 affected over 20 districts in the state and claimed the lives of more than 110 people. The natural disaster, which also coincided with the still ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, caused nationwide concern – but not as much as it warranted by any yardstick.

The 2020 floods once again underlined the disproportionate effects that such disasters have on women. It is a well-known consensus that during and after such disasters, women are faced with incomparable difficulties while also dealing with an unfortunate lack of acknowledgment and support from relevant institutions. It is noteworthy, though, that this gendered issue intersecting with ecological problems is not a recent social evil – it was first dragged to relevance by feminists in the early 1970s, but later got discarded due to internal dissonance among factions.

The current circumstances, however, as we face an impending climate crisis, exacerbated by the ill-treatment of women by patriarchal systems, could warrant a revival of the core ideologies of that discarded branch of feminism.

§

In 1974, Françoise d´Eaubonne, a French author and activist, in her book Le Féminisme ou la Mort (Feminism or Death) coined the term ‘Ecofeminism’ – a category of feminism under which she drew discernible parallels between the oppression of women and the exploitation of the environment by the patriarchal structures of society. Coined during a period when the feminist movement was focusing on integrating women into domestic and societal constructs dominated by men, ecofeminism grew immediately into relevance. This branch of feminism is focused on attaining a society divested of hierarchies, where every living being interacts with the environment equally and in harmony.

Ecofeminism became globally recognised and allied with several movements about environmental issues in the late 1970s and the 1980s and 90s; Kenya’s Green Belt Movement, along with the western pro-environment waves of dissent were the major movements associated with ecofeminism.

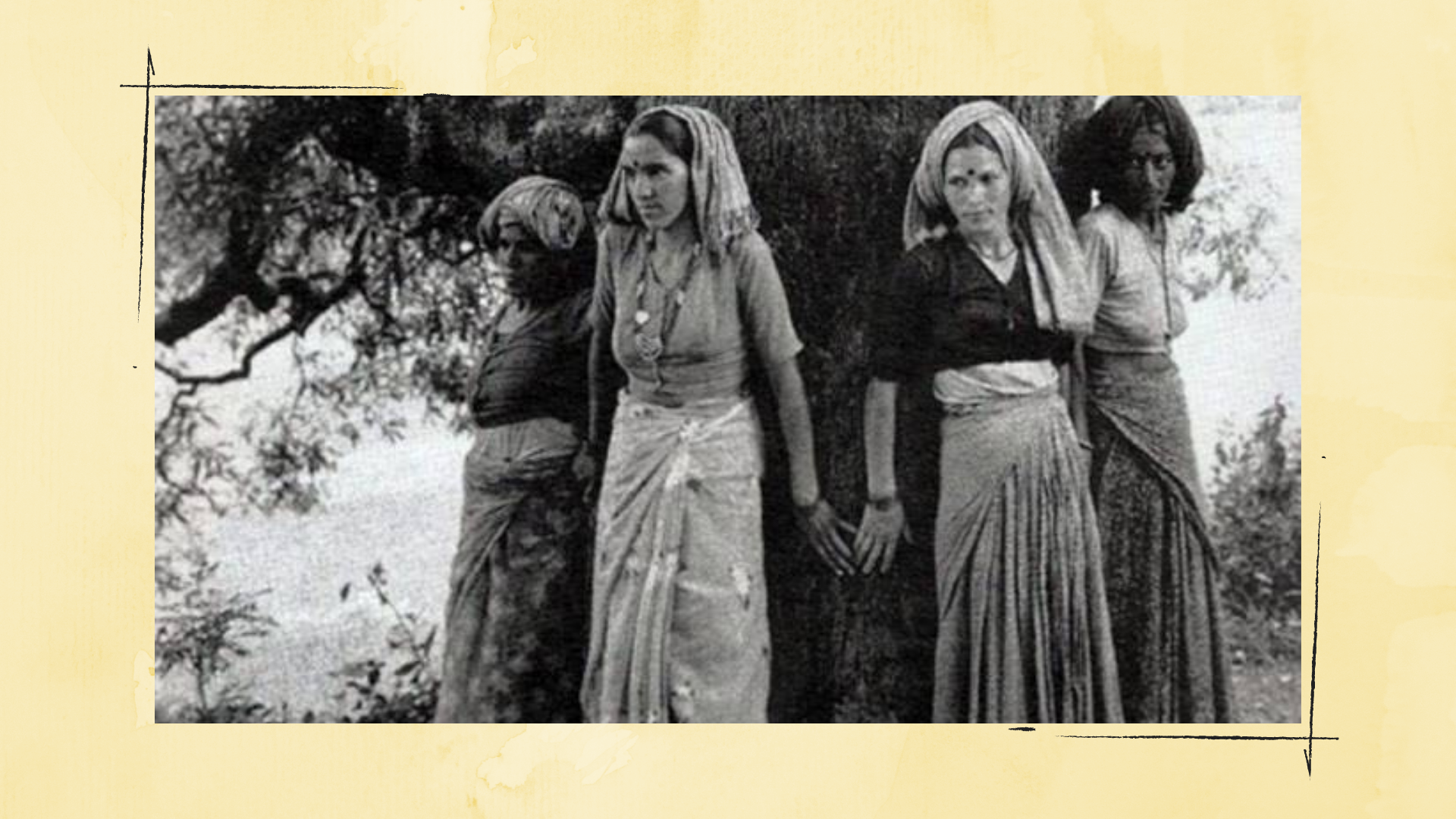

The famous Chipko Movement, too, had its roots entangled with that of ecofeminism. The women in the villages of Uttarakhand were majorly reliant on the local ecosystem for their survival. The gendered division of tasks limited the women’s way of earning a living to the gathering of firewood and the extraction of honey, or any other materials available in the ecosystem, while married women were limited to households. The movement, therefore, witnessed an outpouring of women who came out to protest not just the eradication of the ecosystem but existing gendered practices.

Also read: Climate Change: The Importance of Intersectionality in Environmental Activism

These movements witnessed overwhelming participation and leadership by women that had until then been scarce in the realm of environmental issues.

In its entirety, ecofeminism criticised a variety of things, such as the role of western notions of progress and of disproportionate use of resources by the industrial institutions in harming the environment. It also argued that phenomena such as capitalism and overpopulation were products of the patriarchy, and assigned these factors a gendered male role, while holistically equating women with nature. Eaubonne wrote in her book:

“Profit is the last face of power, and capitalism is the last face of patriarchy.”

It was a firmly held belief that the patriarchal society was similarly exploiting women and nature for the sake of the flawed ideology of progress.

However, by the time the third wave of feminism gained traction in the 1990s, the ideology of ecofeminism started attracting criticism from various feminist factions. The idea of nature being more closely related to women due to its ‘femininity’ and that of the dominant methods of exploitation being ‘masculine,’ created a dichotomy that ironically seemed patriarchal – the dualistic attitude of ecofeminism seemed to stereotypically divide genders.

It, therefore, purported the very notion of sexist categorisation that the feminist movement aimed to abolish. The stereotypical idea to view women’s identity as just an extension of nature betrayed the broader scope of intersectional feminism by not factoring in social constructs such as class, caste, and race into their identities.

The ecofeminist ideology fell prey to its inconsistencies.

§

Coming back to the 21st century, feminism is witnessing its fourth wave, and ecofeminism has lost its relevance. Ironically, at the same time, there is a global climate crisis taking place. An alarming spike in the climate’s temperature, melting glaciers, deficiency of basic resources, increased frequency of natural disasters, and, the most worrisome, our indifference to it all seems like a prologue to a dystopian novel – except it is not fiction. The circumstances which we exist in currently, however, underline a stark resemblance to some of the factors that ecofeminism had highlighted.

According to a report in The Guardian, only 100 corporations are responsible for over 70% of global greenhouse emissions. This statistic plays directly into the perception asserted by ecofeminists that large corporations, piggybacking capitalism, and monopoly held in the market, were responsible for exploiting the various natural resources and ultimately harming the ecosystem. Ecofeminists have often mentioned such corporations or capitalism as the trope for the patriarchal structures of our society – corporations that depend on mass subordination and exploitation to multiply its profits.

Vandana Shiva, an esteemed ecofeminist and environmental activist, has, for many years, criticised the role of such corporations too. The current form of capitalism, according to Shiva, is a “capital working on a global scale, totally uprooted, with accountability nowhere, with responsibility nowhere, and with rights everywhere”. To her, “this new capital, with total freedom and no accountability, is structurally anti-life, anti-freedom”.

Although, the more urgent issue is that the brunt of the consequences is borne by the marginalised section of the population. And, unsurprisingly, women are one of the marginalised groups that are more vulnerable to the adverse effects of the climate crisis.

This unfortunate statistic exists due to several social, economic, and cultural reasons. One of the primary reasons is the fact that women represent the majority of the impoverished.

Also read: Odisha’s Cyclone Fani: How to See a (Natural) Disaster

According to an article published by the UN, 70% of the 1.3 billion people living in poverty are women. These poverty-struck households depend extensively on natural resources for survival, and women perform most of the extensive work involved in the allocation of the available resources. However, they are disproportionately rewarded. For example, women are responsible for 50-80% of global food production while owning less than 10% of the land. The stark divide here can be undeniably attributed to the fundamentally patriarchal corporations that have, for eons, subjected women to subordination and exploited them as cheap labour for profits – the pattern that ecofeminists highlighted three decades ago.

Another report by Thomas Reuters Foundation on how women in India are facing health issues due to the increased water pollution provides yet another instance. According to the report, the Sundarbans delta is running low on freshwater supply, and heightened concentration of saline water is causing tumours, skin diseases, eye infections amongst women who are actively involved in fishing to make a few extra bucks.

Furthermore, the lack of accessibility to technology, resources, and aid leave women vulnerable after every instance of a natural disaster. The increased cases of domestic violence, rape, and human trafficking in the times of disorder further perpetuate their plight; the COVID-19 pandemic is a befitting example.

§

The consensus that has become established is simple and tragic: women are disproportionately affected by the climate crisis. A part of the reason is that they have been forced to exist in a society built on a patriarchal foundation. A design that caters to those on the top rung of the ladder while those at the bottom are subjected to subordination and neglect. The situation, thus, warrants the notion that ecofeminist beliefs are still relevant, and they could be included in the broader banner of the 21st-century feminist movement.

However, for it to be compatible with the current feminist movement, ecofeminism will have to shed its dualist and essentialist values. Instead, it will have to focus on how to integrate women into the roles pivotal to environmental preservation. The lack of participation and accessibilit

Active participation to provide gender-specific ideas regarding adaptation, alleviation, and funding during the times of a crisis is something the redressed ecofeminism can achieve.

The fundamental ideology of ecofeminism to dismantle hegemonic structures must remain consistent, too. The objective is to morph the male-dominated society into a space that acknowledges not only its homogeneous

And from there, in the spirit of making reparations, we might achieve, at best, a society stripped of hierarchies, or, at least, an averted climate crisis.

Aryan Rai is a final-year undergraduate student and a freelance writer.

Featured image credit: Wikipedia/Illustration: LiveWire