The post-Tagorean Bengali writer Manish Ghatak was a pioneer in chronicling the marginalised underbelly of twentieth-century colonial Calcutta with a keen sense of its gendered experience.

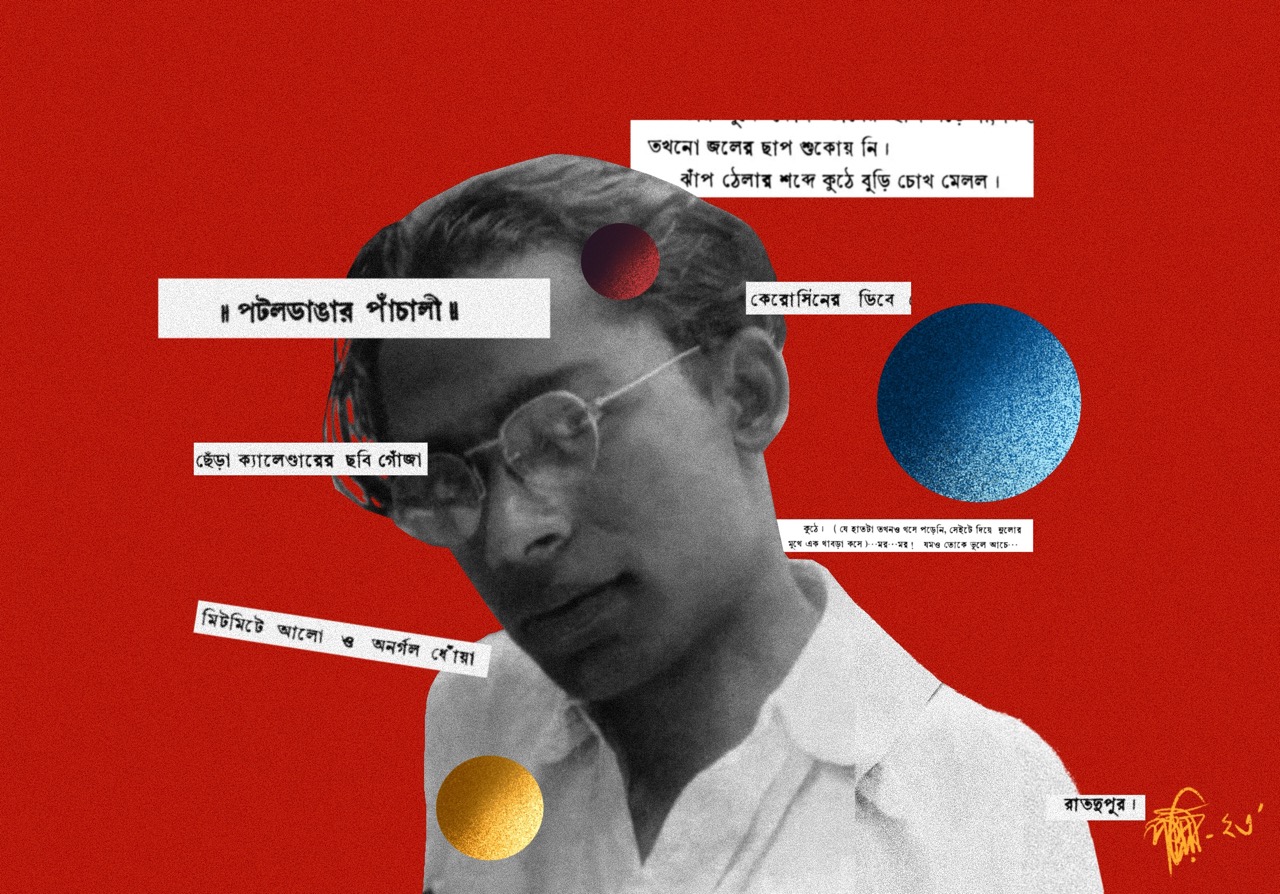

While the despondent lines of Jibanananda Das and the politically charged calls of Kazi Nazrul Islam dominate readers’ memories of the early twentieth-century Bengali literature, specifically the relatively under-researched Kallol era (1923-1935), an equally important, albeit oft-ignored, Kallolean who could be medially placed between the extremes of passivity and utter rebellion was Manish Ghatak (1902-1979). Today better known as the father of the globally discussed author/activist Mahasweta Devi, living on as a vibrant character in her children’s stories, Manish was one of the leading literary figures of the 1920s, writing under the penname Yuvanashva (literally, young horse), whose significance has been reiterated by luminaries like Buddhadeb Basu and Shakti Chattopadhyay.

Originating in the pages of the Bengali magazine Kallol (Roaring Waves), the Kallol movement that began in Calcutta affecting both Bangla poetry and prose can best be understood as an early manifestation of the pre-partition Progressive Writers’ Movement of the 1930s. The young and avant-garde Kalloleans sought to critically articulate societal injustices laid bare by the post-war economic instability as the first step towards social regeneration. Their writings graphically depicted the colonial metropolis through its crowded, unhygienic streets, grime and heat, the miserable state of its education and employment – quotidian experiences of the Bengali lower-middle class that evaded both the aristocratic lifeworld and storyworld of Rabindranath Tagore. Such works that claimed to portray reality more authentically gave unprecedented importance to characters from underprivileged classes as literary subjects, focusing on their ‘unfiltered’ emotions and sexuality.

Manish’s Pataldangar Panchali (The Ballad of Pataldanga) – a collection of short stories published in Kallol from 1925 onwards and finally compiled in 1956 – was responsible, alongside the works by his contemporary Premendra Mitra, for inventing a literary form for ethically relating the slum-life of central-northern Calcutta. In moments of exclamatory inferences or rhetorical questions, Manish’s prose loses the objective narrative style consistent in later writers like Manik Bandopadhyay who deal with equally morbid settings. Yet, the collection certainly shows a progression from Jibanananda’s metaphorical “helpless city’s prison walls”, describing urban decay, to its very physical mapping onto the fictional Pataldanga’s mucky alleys lined with ramshackle cubbyholes – gloom thus transmogrifying into complete squalor, reeking with the stench of pus-covered bodies and rotting carcasses. Equally bleak are the people inhabiting this storyworld – beggars, pickpockets, smugglers, prostitutes – who are almost camouflaged in paragraphs that otherwise describe the surroundings, often forcing the readers to dredge such characters out through careful re-readings. Manish’s writings, hence, were undoubtedly a far cry from Tagorean aesthetics.

Structuring Calcutta’s Slum-life

At the time of its publication, the stories in Pataldangar Panchali strongly offended the Bengali bhadralok or genteel society possibly because the fictional locale of Pataldanga bore an uncanny resemblance to areas adjacent to College Street – the prestigious educational hub of Calcutta since the colonial times. Most of them revolve around the members of an unofficial Pataldanga group whose living quarters can be reached only after plodding through “lane after lane –narrow, broad, shadowy, dark”. The stories themselves are interconnected through the common setting and a handful of recurring characters. This meant that the bhadralok readers of Kallol were made to repeatedly encounter their social others because of the periodic appearance of these stories – effectuating a sociability that could redeem the decaying urban modernity.

The congested spaces that Pataldanga’s inhabitants are forced to share necessitate mutual relationships wherein caste or religious backgrounds become irrelevant. If the induction of new members offers glimpses into how the group may have come to be formed, then the sojourn of bhadralok ‘clients’ in the quarters or the criminal acts performed by the group members in other parts of the city exhibits the group’s connection to the outer world. Any such connection, however, is invariably tenuous for the group functions according to its own dispensation. This means relationships formed with individuals outside the group are doomed and traditional ideas of husband–wife, mother–child, brother–sister are not only discounted but also not tolerated. The stories, therefore, aver the existence of other modes of living, even as the compulsion driving the same makes them poignant.

The democratic nature of these stories is further accentuated by an innovative language usage. The hybrid intermixing of regional dialects with different forms of Bengali along with English, so common in the writings of Mahasweta Devi, appeared for the first time in the works of Kalloleans like Manish. The theoretic division of Bangla into the colloquial chalit and the literary, standardized sadhu meant that the mixing of the two was a strict grammatical no-no. Manish’s use of different languages and dialects in both dialogues and the narrative texts within the same story made him one of the pioneers in breaking the existing norms of lexical untouchability.

Gender at the Margins

The Kalloleans had kept themselves abreast of literary developments all around the world. Manish himself went on to translate a range of poems by the contemporary Chilean writer Pablo Neruda in a collection titled Yuvanashver Neruda (Yuvanashva’s Neruda). In fact, the avowed realism of this group was heavily informed by Marxian dialectical materialism, its popularity surging after the Russian Revolution (1917-1923), and Freudian psychoanalytic theory and its emphasis on the introspecting repressed feelings and memories.

Both of these theoretic strands seem to have influenced Manish’s exploration of the gendered experience of distress. His female characters are shown to be doubly oppressed – firstly, by their crippling economic condition, and secondly, by being compelled to bear the psychological tension of repressing their ‘womanly’ instincts of care, acting on which always worsens their already precarious state in Manish’s storyworld. Such characters, therefore, become particular instances of the nefarious effects of urban modernity that steadily drains people of their humanitarian qualities.

Over the last century, especially with the prominence of identity politics, characters from oppressed classes that formerly populated magazines like Kallol have gained increased representation in Indian literature, not only in the writings of class/caste ‘elites’, but also through works by authors coming from such marginalised backgrounds. The significance of Pataldangar Panchali lies in its early recognition of the differential experiences of people living in different quarters of the same city. It asserts that to truly redeem the ‘self’, its difference from the ‘other’ must first be known, and then, bridged through the realization of an ultimately shared humanism that, as Manish writes, connects “the silk hat” with “the torn blanket”.

Sragdharamalini Das is an independent scholar interested in the late-19th and 20th-century Bengali and Hindi literature. She is currently working on the prose fiction of the Bengali author Mahasweta Devi.

Featured image illustration by Pariplab Chakraborty