In the suburbs of Bandra, sits a Mumbai few have known. With Gaonthans (fisherfolk settlements) and the Koli community still claiming parts shared by migrant marquee residents, the landscape is a cultural weave of street art and the frayed ends of Bollywood. Bandra stands as a melting pot of demographics, ‘cool’ migrants, religious identities and the juxtaposition of freshness with the facade of the familiar. Calling this urban imagination, with its craft beers , pub-grubs and promenades, a product of gentrification would be discounting its blanket state of flux.

This location’s malleability is mirrored by Dome’s Dali-esque wall art titled ‘Coming Home’, depicting the ‘urban poor’ fisherman with a cow’s head, on a cycle with the day’s catch and a guitar.

Similarly, in Delhi, Shahpur Jat and Hauz Khas village became street galleries overnight but showcased a stark contrast in the way they became represented over the years – a micro reflection of space politics resulting from artistic insertion. Hauz Khas has become a homogenous sub-centre for patrons, pricy pastels and pulled pork on the weekends, with locals hidden away behind cab fares and cash counters. The urban ‘bohemian’ sensibility of its art and culture remain highlighted by the ‘dumpster graffiti’ but is lost in light of the space’s developed commerciality.

Providing a contrast to this streamlined locale is Shahpur Jat and its diverse retail platform. Remnants of pre-existing rural neighbourhoods have been washed out by gentrifying factors cloaked in the garb of aestheticism and re-imagination. Artists painted in hidden, residential areas inhabited by the working class. The difference in canvas spaces between the two urban villages, begs important questions– are some canvases more important than others? Who is this art really for? With locations such as these morphing into museums for street artists, the discourse surrounding the artwork’s contribution to property value spikes and ‘urban’ cultural ethos becomes important.

There exists a thin line between local reclamation and calculated attempts at selling a lifestyle.

Certain canvases stand vulnerable in the face of gentrification and morally driven artists’ ‘saviour complex’ – a phenomenon taking local ghettos by storm. Dharavi, for example, is becoming a desired canvas for contemporary graffiti artists. In an interview with The Hindu, one artist manager revealed an inherent discomfort with external sources, “Why should these fancy artists, who never cared about Dharavi and looked down upon us in the past, now come here and show off their skills?”

Local representation, by marginalised communities, is being de-platformed by famous craftspeople who can afford the equipment this art form requires. Admittedly, dissent is key to a functioning democracy. Artists like Daku, with his ‘middle finger’ marked with voter’s ink, portraits of a Modi fallen and ‘Fuck’ painted across nine buildings to defy ACP Vasant Dhoble (after his crackdown on street art), create platforms for protest.

However, does it remain participative allyship when these artists hijack the creative spaces from the same minorities their art seeks to benefit?

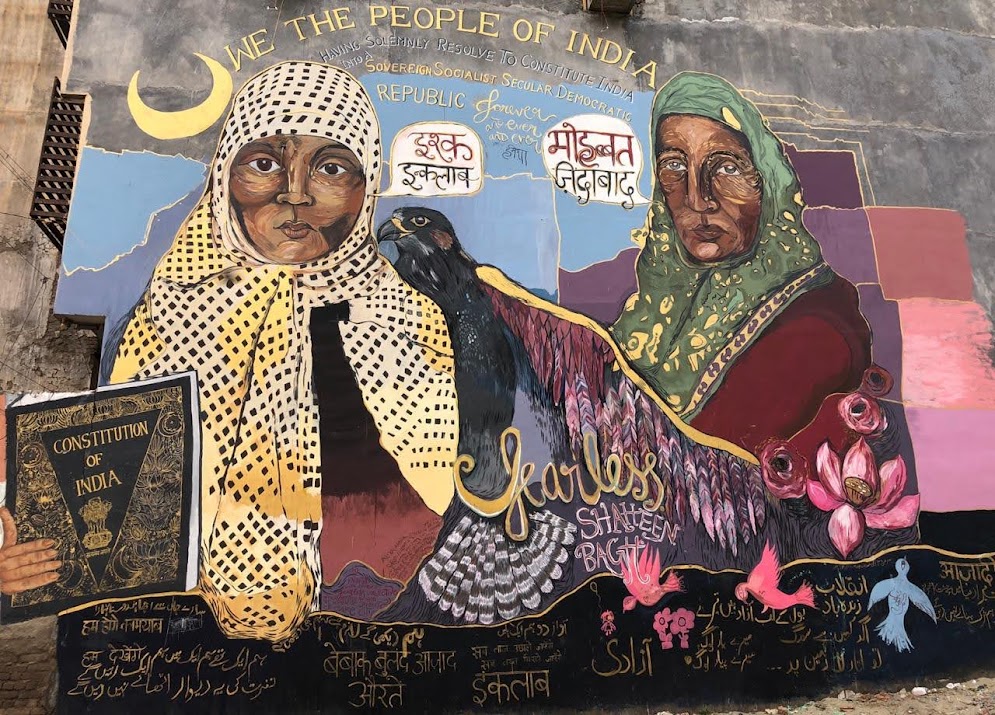

Shaheen Bagh wall art. Photo: Shanaia Kapoor

The question is an important one. Is it ethical for art representing minorities, to be created by artists so far removed from their reality? It is tricky because when allyship comes into play, the line between advocacy and annexation wears thin. Admittedly, it has always been said that those with established platforms and privileged identities, maintain the responsibility to communicate on behalf of those who ‘can’t’. However, this notion of ‘voicing for the voiceless’ has survived thus far only because those with minimal platforms have never been left any space to occupy.

It is a cycle that cannot be broken until minority artists are given the platform to reclaim and represent their own cultures, conflicts and creativity.

Delhi University’s ‘Wall of Democracy’, JNU’s protest art against caste politics, AFSPA, economic liberalistion politics, etc. and Shilo’s murals tackling discomfort with dialogue on women’s issues, all provide a starkly different take on street art and graffiti when compared to metro cities’ posher postal codes. However, with politically coloured and provocative art, comes the wooden gavel of selective censorship that manages to whitewash acts of expressional dissent, under the pretext of rigid legalities.

Narrowly escaping the Prevention of Defacement of Property Act 2007 and Damage to Public Property Act 1984, graffiti has a history of defamation on the grounds of distraction resulting in a threat to road safety, defacement and outright vandalism. This makes issuing arrest warrants a subjective action. There have been incidents in the past, where walls were painted over, whitewashed, and redone by authorities under the pretext of eliminating threats to the safety of people and property.

Censorship is detrimental to artists’ careers. To be able to exercise freedom of creativity and expression within a political framework such as India’s is nearly impossible. However, the mere ability to separate art from politics is a product of having an identity that is situated in socioeconomic and political privilege, where oppression isn’t personal. Kashmir, for example, upholds public art as a method of protest. Reflections of this can be seen in the portrait of JKLF founder, Maqbool Bhat or on a wall near Jhelum river, painted over with protest graffiti – one of the few remaining forms of dissent in the Valley.

Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh saw a similar movement, where art and installations occupied every corner as methods of protest against the Citizenship Amendment Act and National Register of Citizens. A 40-foot iron structure carved in the shape of India’s map with “Hum Bharat ke log CAA-NPR-NRC nahi maante (We the people of India reject CAA-NPR-NRC)” stood in its centre. There was also a replica of India gate, drawn over with the names of people who lost their lives in the preceding violent outbreaks that occurred as a result of the protests.

In The Practice of Everyday Life, Michel De Certeau argues, “Space is a practised place… It occurs as the effect produced by the operations that orient it, situate it, temporalize it, and make it function in a polyvalent unity of conflictual programs or contractual proximities.” Space, public or private, cannot, therefore, be apolitical. However, some canvas spaces are deemed more disposable than others, while artists under administrative occupation struggle to grapple with rigorous censorship.

Whether it is in Shahpur Jat or Srinagar, Hill Road or Hauz Khas, Dharavi or DU, street art maintains a purpose, but the art world has revealed a hierarchy of canvases. It is one that privileges an urban-elite – ‘woke’ and ‘cultured creators – providing a stark binary in patterns of consumption. Seen occupying most realms of expression, it is important for these creators to step back and maintain allyship without de-platforming local artists or disrespecting a space’s origin by imposing ideas of newness or reformation.

Shanaia Kapoor is an undergraduate student at Ashoka University and a freelance writer for various online publications.

All images provided by the author